The New Neo-Primitivism

Rodion Kitaev. Le vin q’on boit par les yeux. Exhibition view. Paris, 2024. Courtesy of Iragui Gallery

If a century ago naive art was an important source for the avant-garde, is once again becoming a creative refuge for Russian artists of a new generation. Millennials such as Rodion Kitaev, Galya Fadeeva and Alisa Gvozdeva are following in the footsteps of the European Surrealists who often turned to the aesthetics of primitivism to create mind-boggling visual conundrums.

Through reflections on the work, personalities and artistic statements of three Russian millennial artists Rodion Kitaev (b. 1984), Galya Fadeeva (b. 1991), Alisa Gvozdeva (b. 1996) you encounter an engaging, childlike perception of our world. Their flight into the naïve is perhaps therapeutic, as a young artist with neuroticism biting at the foothills of a fledgling career, the need to find one´s own personal artistic mission can become so frustrating that one solution is to simply stay in the nursery. Instead of interacting directly with the traumatic realities of our contemporary life, or turning to socially relevant narratives, primitivist artists tell fairy tales and invent stories about fictional characters. Although as a society we do not place any value on infantilisation – usually the reverse – when it comes to figurative primitivism this is a compelling trait. We all somehow live in the hope that beneath its surface large and important meanings continue to mature and take shape.

From 1932 and until the breakdown of the Soviet Union culture existed under an indiscriminate and authoritarian form of control and to varying degrees, the mask of the simple fool or follower of naïve aesthetics saved artists such as George Rublev (1902–1975) and Yuri Vasnetsov (1900–1973) from ideological pressure and helped them to survive. In the second half of the 20th century interest in folk art legalised artistic techniques and practices that differed from Socialist Realism and Soviet artists connected with the pioneers of primitivism amongst the Russian Futurists: Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964). The pictorial qualities in folk pictures had its uses in late Soviet era doublethink. In the art of Alexander Maximov (1930–1992) or Semyon Bely (1938–2010), the life of a Soviet citizen, whether at work or rest, took on playful forms evocative of Russian lubki (folk prints), a kind of acceptable response to the thoughts of the founders of the communist doctrine about the role of labour in a bright future. During the 1970s, interest in primitive and naive art became an important part of the general intellectual atmosphere, even to the point of attempting to interpret the activities of non-conformist artists (who were not members of official creative unions) within the concept of ‘urban folklore’. Among the artists who made primitivism the basis of their own recognisable styles are Vladlen Gavrilchik (1929–2017) and the Leonid Purygin (1951–1995). For them primitivism and naive art were not so much a breakthrough to primordiality, raw emotions or bright colours as it was at the beginning of the twentieth century, more as opportunities for escapism.

The aesthetics and images of Primitivist art were firmly established in Surrealism, which from the beginning was attentive to art brut and the naïve. Evidence of this can be seen in a photograph taken in 1942 in New York in which André Breton (1896–1966), Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), Max Ernst (1891–1976) and Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) are gathered around the famous primitivist Moritz Hirschfeld’s painting ‘Nude at the Window’. Surrealist works do not lend themselves to being deciphered, which is also true of naïve art, whose enigmatic nature is an extension of a syncretic perception of the world. The naive tradition includes both folklore and Art Brut, which Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) brought to the art scene. The Surrealism of British, American and Mexican artists was particularly characterised by fairy-tale leanings, picked up by a new generation.

Young artists generally combine sources with ease and freedom and their works look like rebuses that cannot and do not need to be solved – one of the conditions set by the Surrealists. In this way, new worlds are gradually formed and built that are not inferior to the dreams of the avant-garde artists of a century ago, which without any claims to world domination makes the creations of our contemporaries even more attractive.

Moscow-born Rodion Kitaev now lives in France and two solo exhibitions have opened this autumn in Russia and France: ‘It’s Never. Kitten Is Flying’ at Name Gallery in St Petersburg, and ‘Le vin que l’on boit par les yeux’ (The Wine We Drink With Our Eyes) at Iragui Gallery in Paris, shows which combine painting, embroidery and objects. Kitaev is a graduate of the Moscow Polygraphic Institute, and his works demonstrate continuity with the Soviet classics of children's book illustration who emerged from the same institution, notably Viktor Pivovarov (b. 1937). In his version of Surrealism Kitaev is interested in unobvious, secondary characters, the title of the Paris exhibition is a line from the French poet Albert Giraud’s debut collection of poems in 1884, which was previously used by Arnold Schoenberg in his cycle ‘Pierrot lunaire’ and Canadian director Bruce LaBruce, who made a film of the same name in 2014. The title of the St Petersburg exhibition refers to the title of the novel ‘Kitten Letaev’, written a century ago by Russian poet Andrei Bely.

The rainbow chromatic background of his paintings points to a dreamlike space outside of time, full of small details: toy trains are travelling, gnomes that have left their book houses and cats and birds walking around outside the pages of books they have left. Just as with Max Ernst, the image of birds is important in Kitaev’s work: a small bird with yellow plumage appears in his paintings and embroideries, flying from one work to another. “I associate birds with death,” says Kitaev, describing an experience from his childhood: “My grandfather was brought to his one-room flat and until the funeral the coffin stood on the table. While everyone was asleep, I studied the corpse in the morning sunlight. At that time, I knew two signs of imminent death – a broken mirror and a bird that flew into the window. It seemed to me that a bird flew out of the mirror and broke it – the cracks on the glass were associated with a bird hitting an invisible barrier”. In the projects he has created in France, the artist continues to gather his childhood experiences as well as the childhood fears that shaped him. In the video that concludes the exhibition at Name Gallery, Kitaev buries a dead goldfinch.

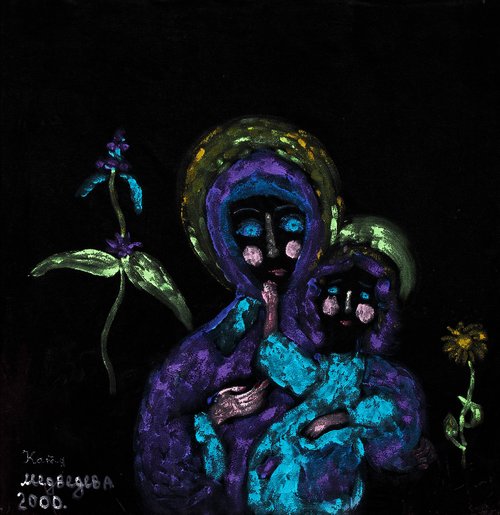

Galya Fadeeva’s first solo exhibition will open at the same gallery in St Petersburg in on 12 December. This Crimean-born artist, who lives and works in St Petersburg, having studied at Anatoly Osmolovsky’s (b. 1969) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) Baza Institute in Moscow. Her project, which includes painting, works on paper and ceramics, is called ‘The Fortress of Mole’s Feet’. According to the artist, “the exhibition will have the structure of a graphic novel, the content of which the viewer will read from the walls”. Moles are the artist’s alter ego: “Moles are ‘embedded’ in the earth and adapted to underground life like no one else,” she explains.

The moles in the inner world of Fadeeva, who names Swiss artist Unica Zürn (1916–1970) and British-Mexican Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) among her artistic references, are absolutely real. Fadeeva tells how her characters changed while the project was being prepared: “When you create a work of art, the liveliness is drained out of the moles and they become stone. In my works there are moles in a hybrid state – either they are roots, or they are creatures sprouting long branches. I realised that these are moles that have already died and have become so stuck together that they have formed a new hybrid within this world.”

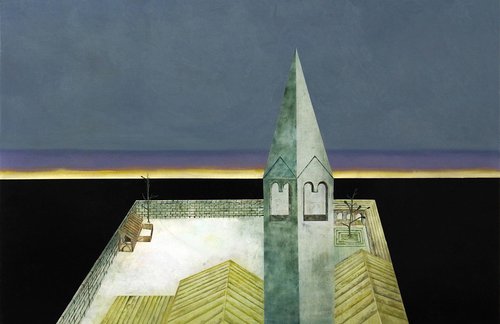

Like Fadeeva, Alisa Gvozdeva is also mostly self-taught in art: she graduated from the Faculty of Liberal Arts at St Petersburg University with a diploma in cognitive research. The artist’s CV so far includes one solo exhibition entitled ‘Foolish Soul’ at St Petersburg’s Luda Gallery last spring. Over the past two years Gvozdeva has been living in Armenia and France, taking part in art fairs and organising online exhibitions of her work, as well as performing in the musical duo ‘Miss Mårble’.

Gvozdeva calls her characters ‘The Fools, the Lepers, the Saints’, all beings who live in a separate space, fenced off like a garden of Eden or a castle in a private estate like you see in medieval miniatures such as the ‘Books of Hours’ or in Lucas Cranach’s ‘The Source of Youth’. Gvozdeva loves the work of Hieronymus Bosch and Henri Rousseau. Just like Rodion Kitaev or Galya Fadeeva, her pictures are filled with a multitude of interconnected details, which in the picture exists cohesively and harmoniously with text, a quality you often see in primitivism and naive art.

“In the process of drawing, I get so immersed inside myself that it is as if I stop existing in reality. I do not have a romantic or intellectual creative process; it is more something which I think is on the autistic spectrum. It is about stopping time, life, reality, me. I have a rather unruly imagination, vivid dreams and a playful mind, with lots of stories to tell. At root there is of course an escape from outside reality, no matter how banal it may be”. It seems that today many artists both young and old are ready to sign up to these words of Alisa Gvozdeva.

Rodion Kitaev. It’s Now. Kitten is Flying

St. Petersburg, Russia

15 October – 30 November, 2024

Rodion Kitaev. Le vin q’on boit par les yeux

Paris, France

5 November – 22 December, 2024