The forbidden art of the GULAG

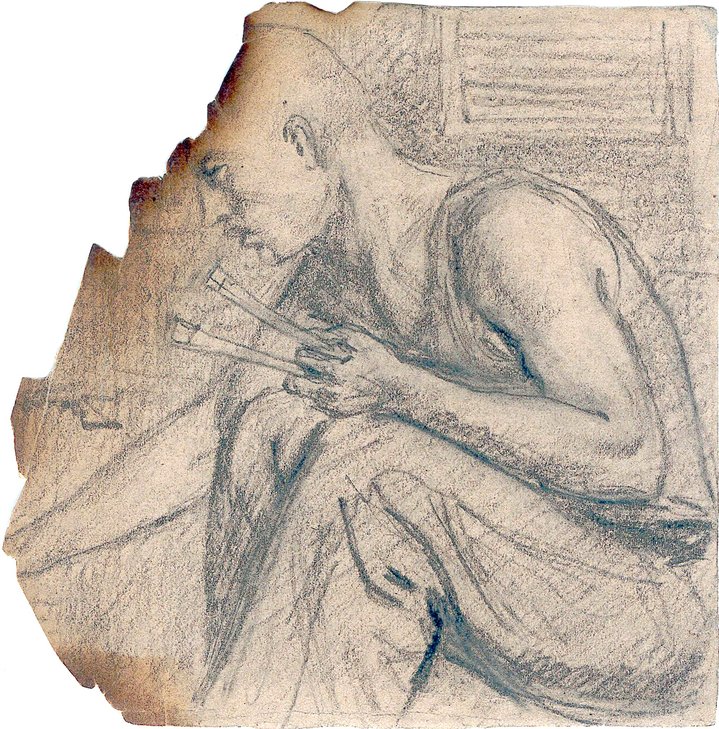

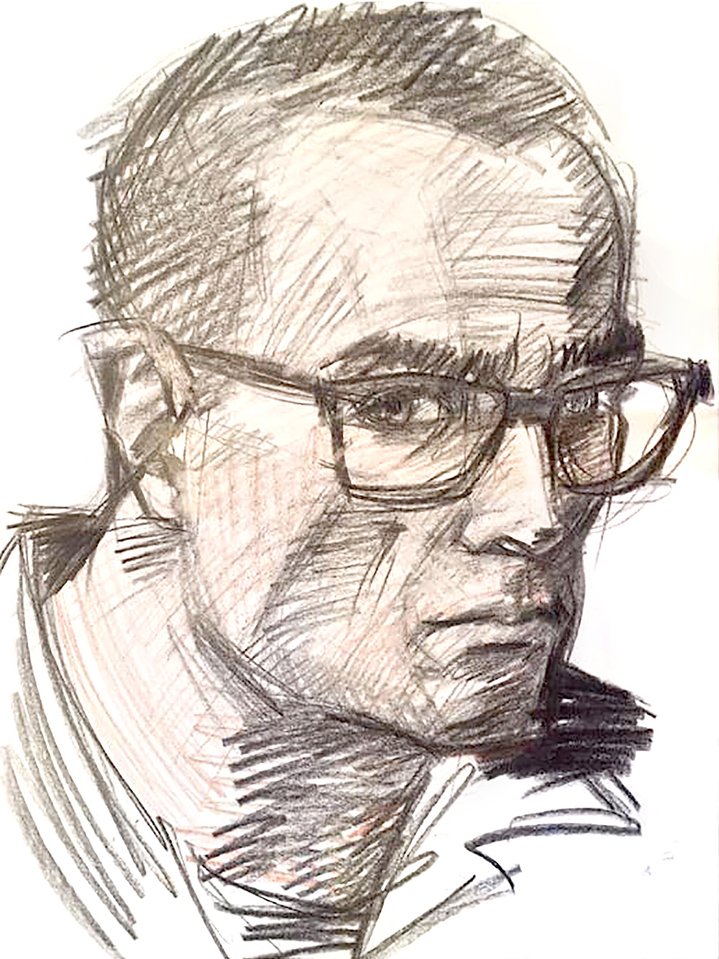

Yulo Sooster. Prisoner. Karlag, 1950. Courtesy of togdazine.ru and International Memorial

The only remaining fragments that document the horror endured by millions.

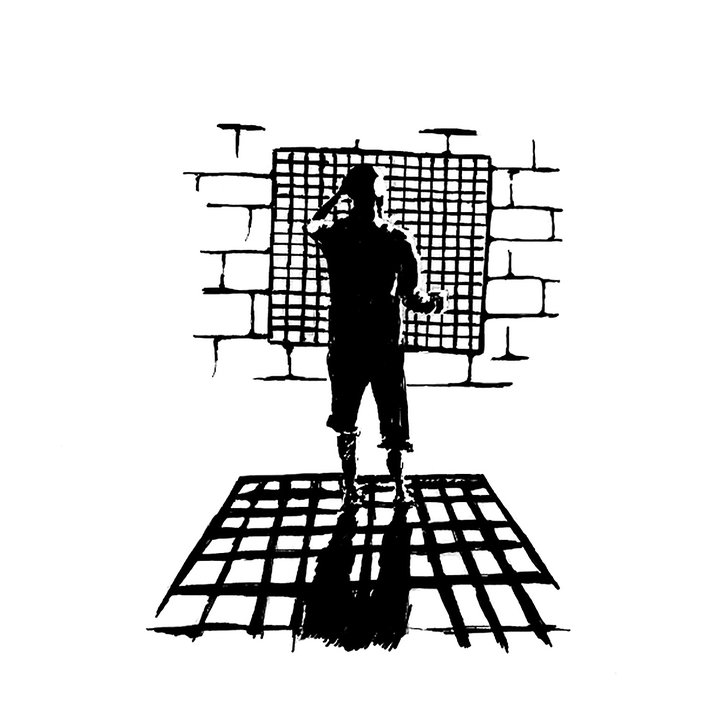

The prison camps of the Soviet Union were a self-contained universe that left very few visual traces. The world outside the Soviet empire first learnt about those forced labour camps through works like Alexander Solzhenytsin’s ‘The GULAG Archipelago’, smuggled out of the Soviet Union and published in 1973. But with the exception of a few scattered photographs, the only remaining visual record are drawings, paintings, sculptures, and diaries made by a handful of survivors, most of them created from memory after release from the camps.

Beginning with the establishment of the first prison camp on the Solovetsky Islands in Russia’s White Sea in 1923, and formalised with the infamous 1929 law “on using the labour of prisoners,” the GULAG -a Russian acronym of the Main Directorate of Corrective Labour Camps - formed a network that spanned every part of the empire and drew citizens of all walks of life to that hell on earth, including artists.

At Vorkutlag, a coal-mining camp just above the Arctic Circle, NKVD general Vladimir Maltsev proclaimed, “Here, in the Polar region, in conditions of polar nights and permafrost, we must create a bright and appealing theatre, happy and lyrical.” Many were saved by the GULAG’s thirst for theatrical performances, including artists who created the decorations. However, this officially sanctioned work represents only a fraction of all artistic activities at the heart of the monster. What left a more serious shadow, was what prisoners created when they turned their talent toward the GULAG itself.

The visual artists of the GULAG fall into two rough groups: those who produced works during captivity, and those who did so after. What has been handed down from the former group is, naturally, much smaller. The possession of artistic implements by unauthorised persons was punishable by confinement, extended sentences, and/or hard labour. Meanwhile, those who worked “on the outside” had to work in secret, hiding their works from the police and neighbours for fear of further repercussions.

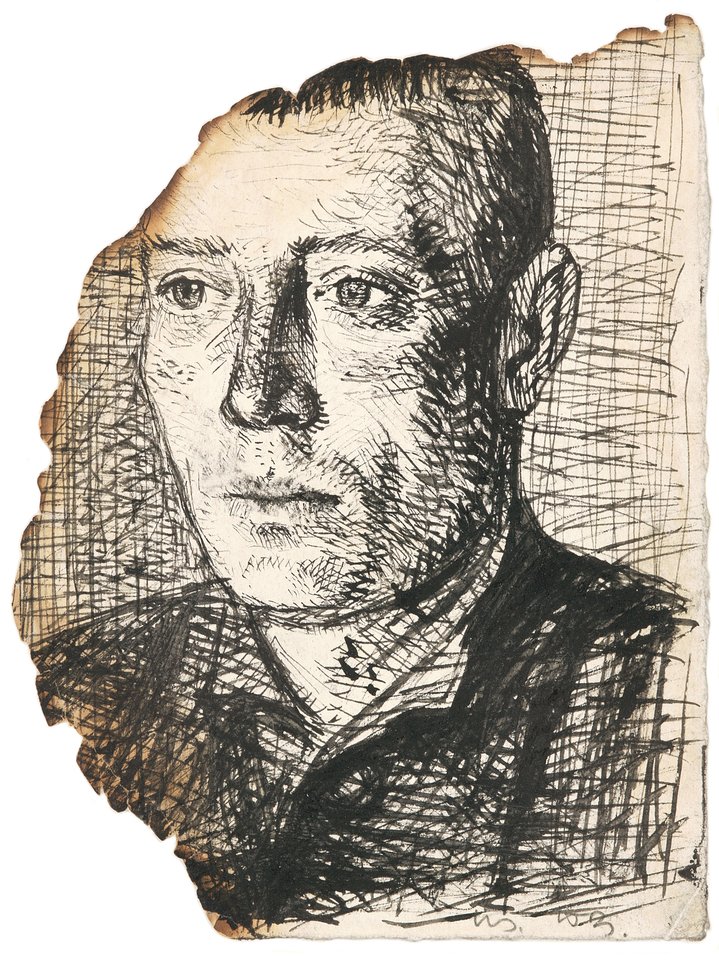

A member of the first group, Boris Sveshnikov (1927–1998) was arrested as a 19-year-old student for participating in a “terrorist plot”, and sent to the Ukhtizhemlag, a mining and chemical processing camp in the Komi Republic. His drawings, done on stolen paper in his night watchman’s booth, bear a striking resemblance to classical landscape engravings, with a hint of dark surrealism: Siberian landscapes are dotted with jagged fragments of barracks and camp facilities perched on precipices, inhabited by nurses, doctors and emaciated, naked bodies of prisoners.

Most stunning of all are the huge empty spaces in his work, glaring out at viewers not as an invitation to fill in the blank, but rather as a warning of a blank too horrifying to fill. In 1950, he wrote in a letter home, “I never draw from nature. [...] The will of my unconscious is stronger. I haven’t looked at the sky or at people for two years now.” His was a rare case of relative freedom in the camps: an enormous number of his works survived, and his later pieces pale in comparison to the poignancy of what he accomplished in captivity.

Not all artists could be as productive on the inside. One of Sveshnikov’s campmates, Lev Kropivnitsky (1922–1994), was arrested together with him on the charges of “anti-Soviet terrorism”. Some of his drawings made in the camp have survived to the present day. Upon his eventual rehabilitation, he used abstract painting as a way of engaging with the jarring realities he had faced, and upon returning to Moscow, began to take part in unofficial art circles and was even accepted into the Union of Artists in 1973.

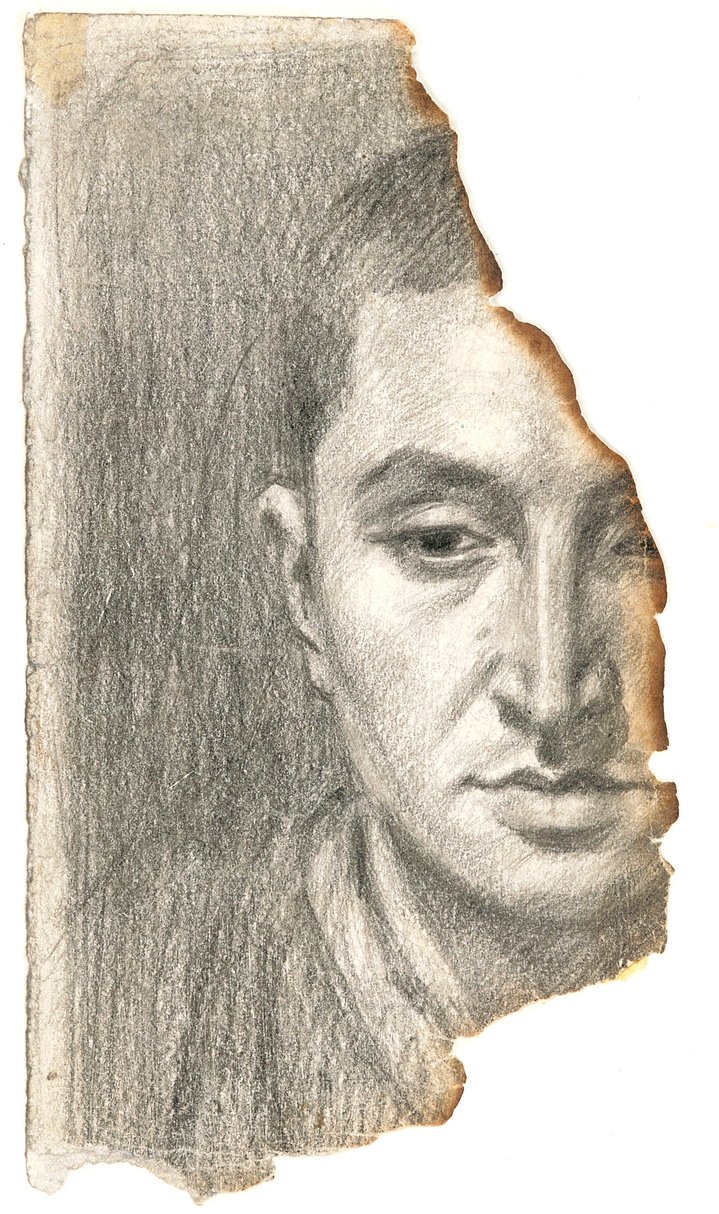

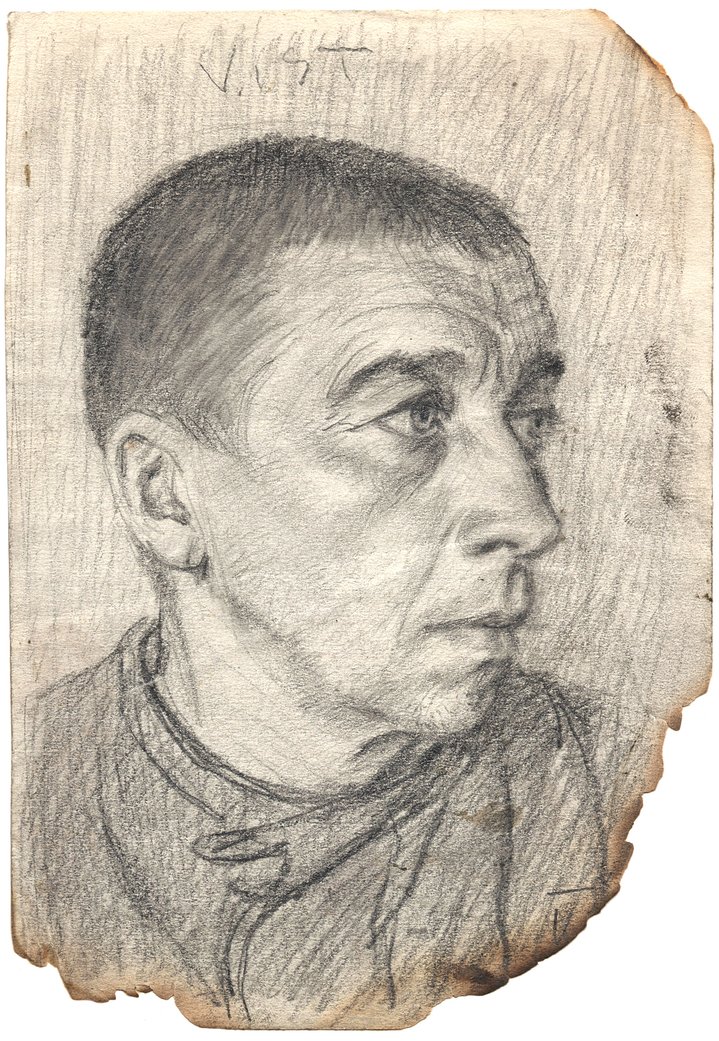

Prominent Estonian artist Yulo Sooster (1924–1970), who would become an important figure of the underground art scene in USSR in the 1960s, was sent to GULAG in 1949, along with a group of young people accused of anti-Soviet propaganda. He was released in 1956, three years after Stalin’s death. He illustrated letters to his wife-to-be with camp scenes and even managed to earn money by drawing highly realistic portraits of his fellow inmates at night, which he then sold to them for five roubles each. That style was, of course, a far cry from surrealistic and abstract imagery he embraced on regaining his freedom.

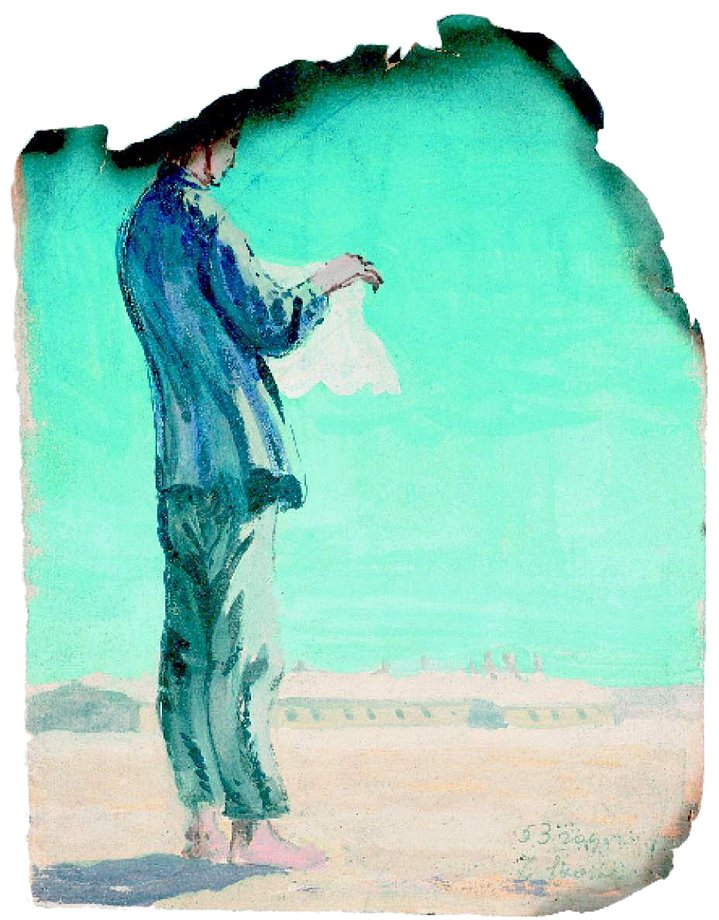

Trained as an artist in the legendary studios of VKhUTEMAS under avant-garde painter Robert Falk (1886-1958), Eva Pavlovna Levina-Rozengoltz (1898-1975) had a successful career as a textile artist until her arrest in 1949, when she was sentenced to 10 years of exile in Krasnoyarsk Krai. In addition to working in the camp’s logging operation and hospital, she made patterned textiles and painted on oilcloths and wooden plaques to earn money, occasionally sketching landscapes in ink and watercolour in her free time. Upon her own return to Moscow, she, like Kropivnitsky, began to process her experience through drawings. Her works illuminate a stunning artistic path from her first ‘Rembrandt Series’ of 1957-1961, through her icon-esque group portraits of the mid-1960s, all the way to her haunting “plastic compositions” of the early 1970s. In contrast to the cliche of a survivor frozen in time, this artist instead continued to grow with age, finding ever new techniques to represent her formative trauma.

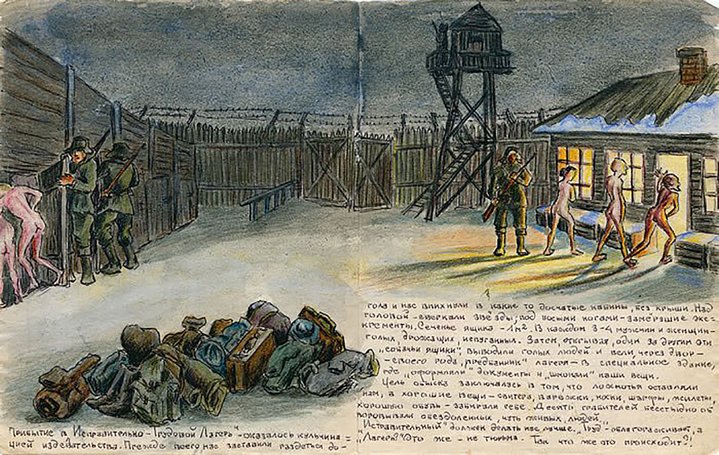

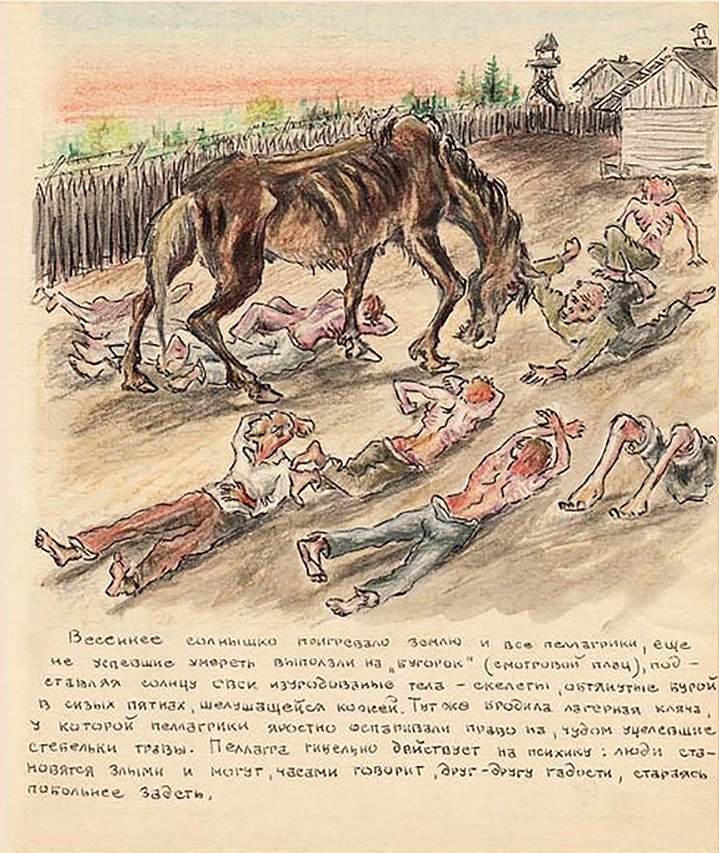

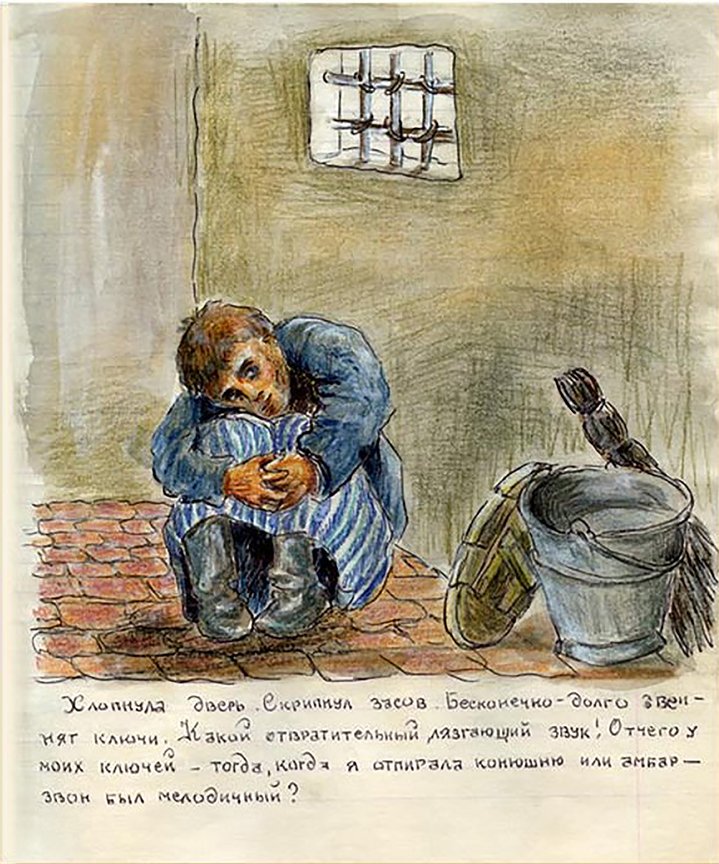

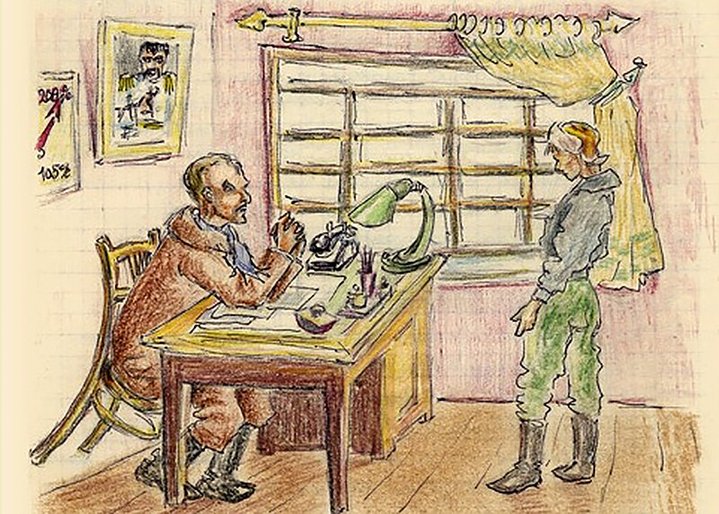

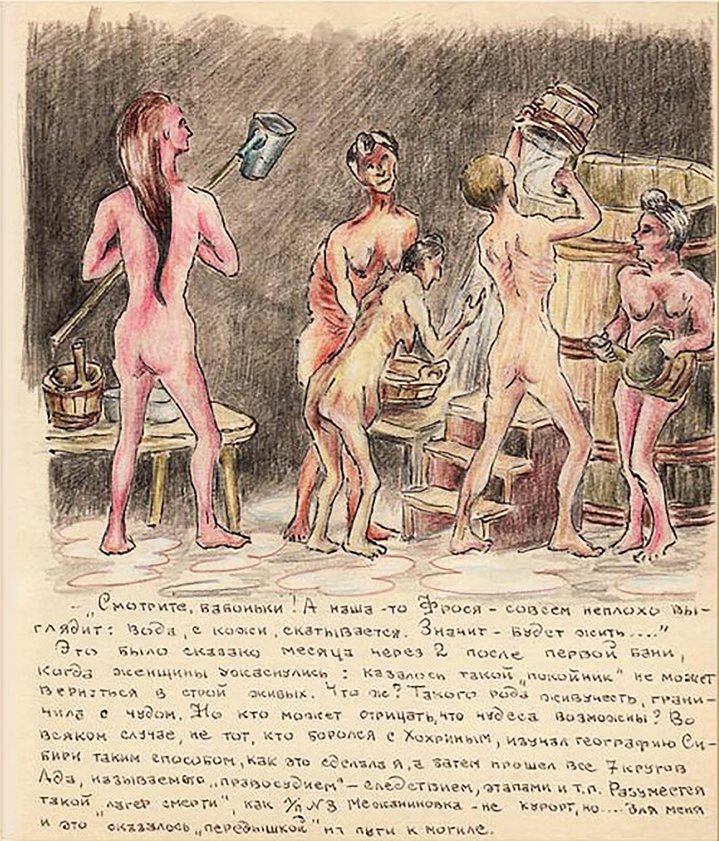

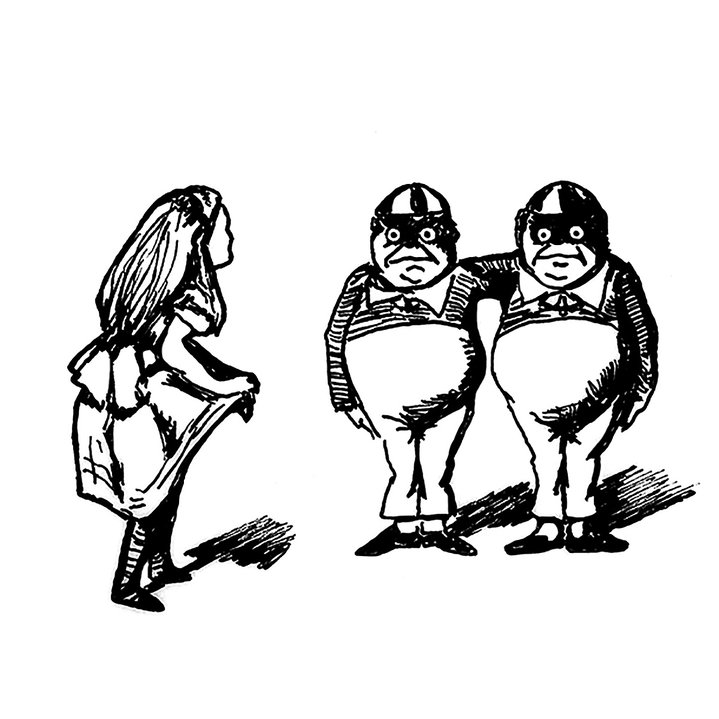

Amateurs, too, took up the mantle of chronicling the human experience’s terrifying extremes in the camps. One was Evfrosinia Kersnovskaya (1908-1994), who would become a folk hero among Russian historical memory activists. Born to a minor Russian nobleman in Odessa, she fled with her family to Bessarabia (now Moldova) in the early Soviet years. Kersnovsakaya was first arrested as a landowner in 1941 and deported to Siberia. She was arrested again after she had made a 1,500-kilometre prison break across Siberian taiga. Such a story is worthy of its own book - one that she herself wrote. After she was freed and rehabilitated, she dedicated five years from 1964 to 1968 to chronicling her former prison life. This triumph of samizdat, called ‘How Much A Person Costs’ (Skolko stoit chelovek), brings up myriad of associations, including Russian lubok folk art, comic books, and caricature. In it, Kersnovskaya pulls no punches, portraying scenes of both nightmarish horror and human vulnerability with the quick hand and sharp eye of a court reporter, and recalling every step of her harrowing journey.

A similar dedication to documentary characterizes Nikolay Getman (1917–2004), who was arrested for a sketch he made of Stalin on cigarette paper, and spent nearly eight years in the Ozerlag and Kolyma camps. Upon settling in Magadan with his family after the end of his prison sentence, he began to study painting, and devoted himself to representing his experience in a similar documentary tradition. Although he became a member of the Magadan Union of Artists in 1964 and even a popular illustrator in the Soviet press, the core of his creative efforts - his recollections of camp life in acrylic and oil only saw the light of day in 1993.

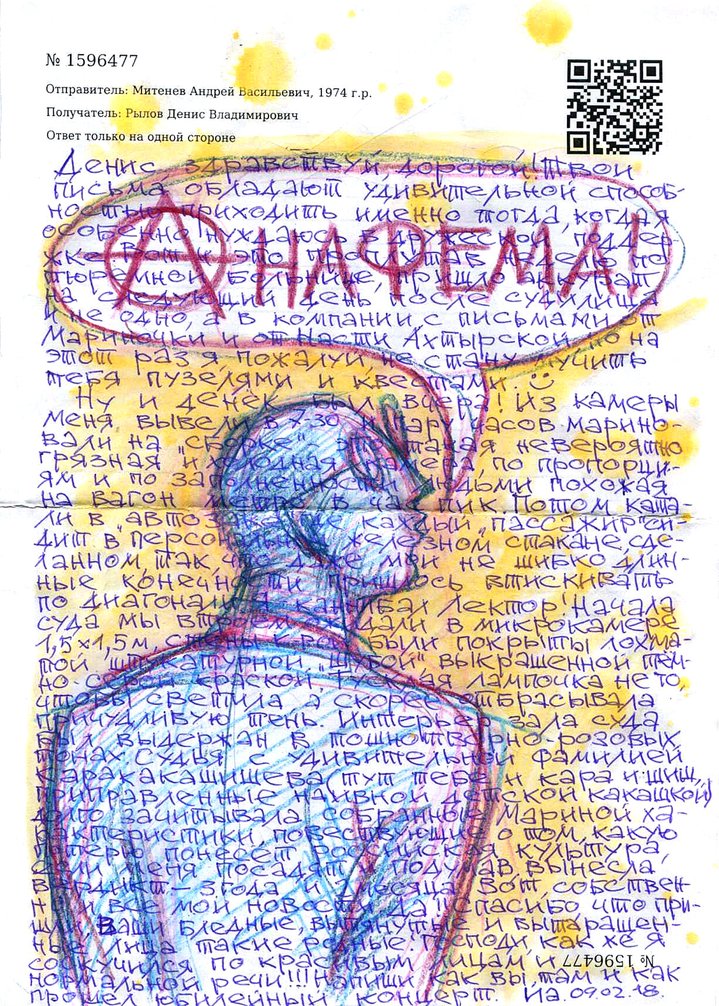

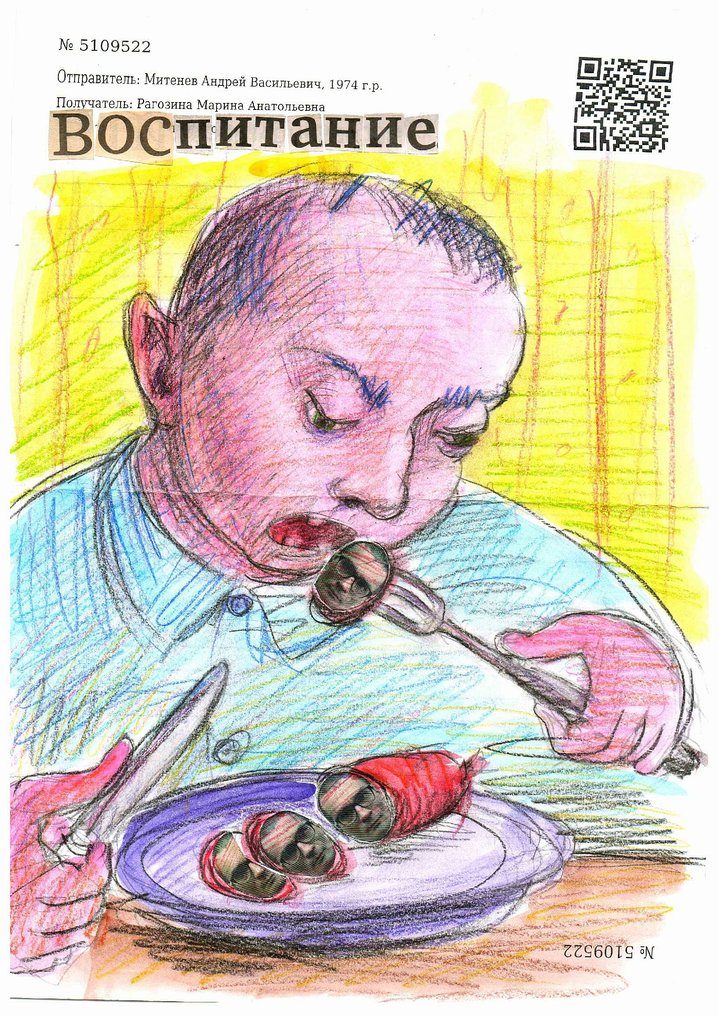

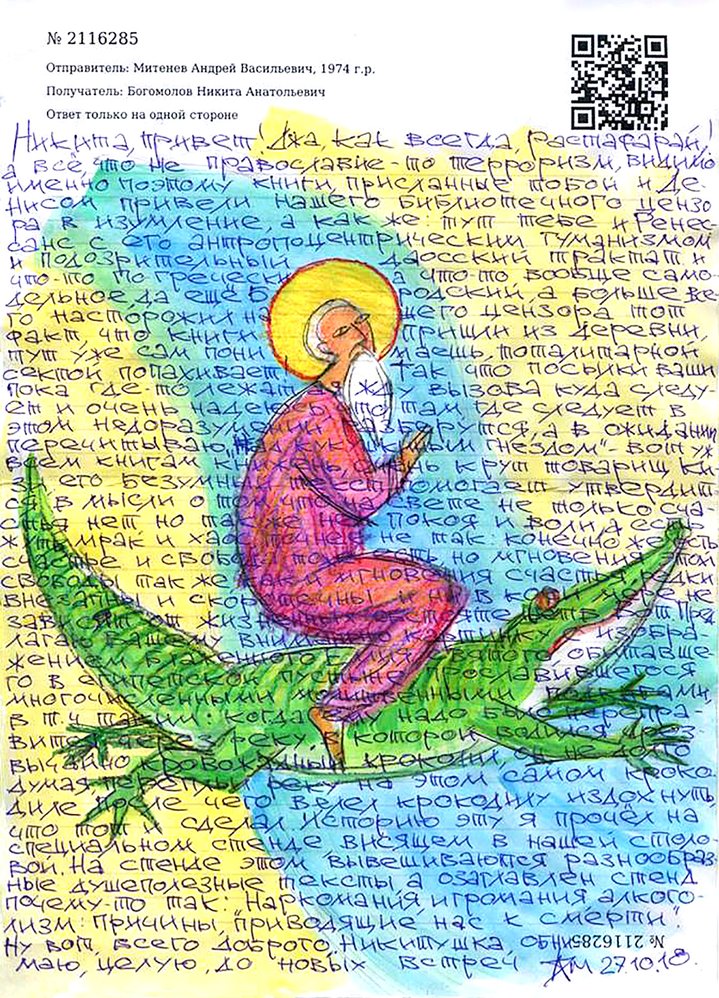

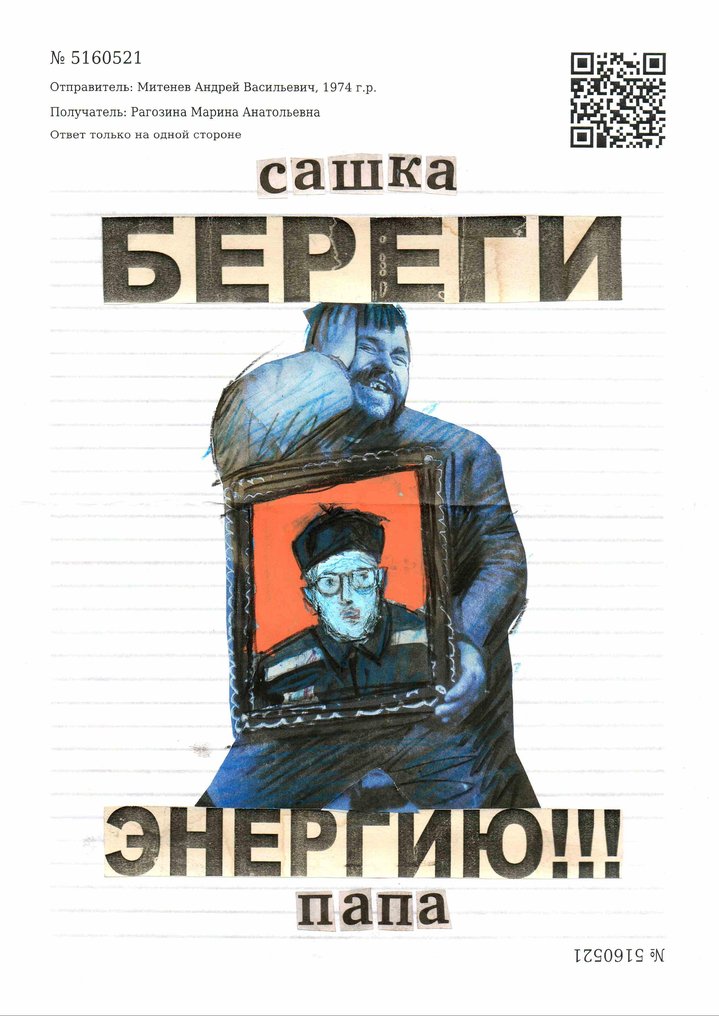

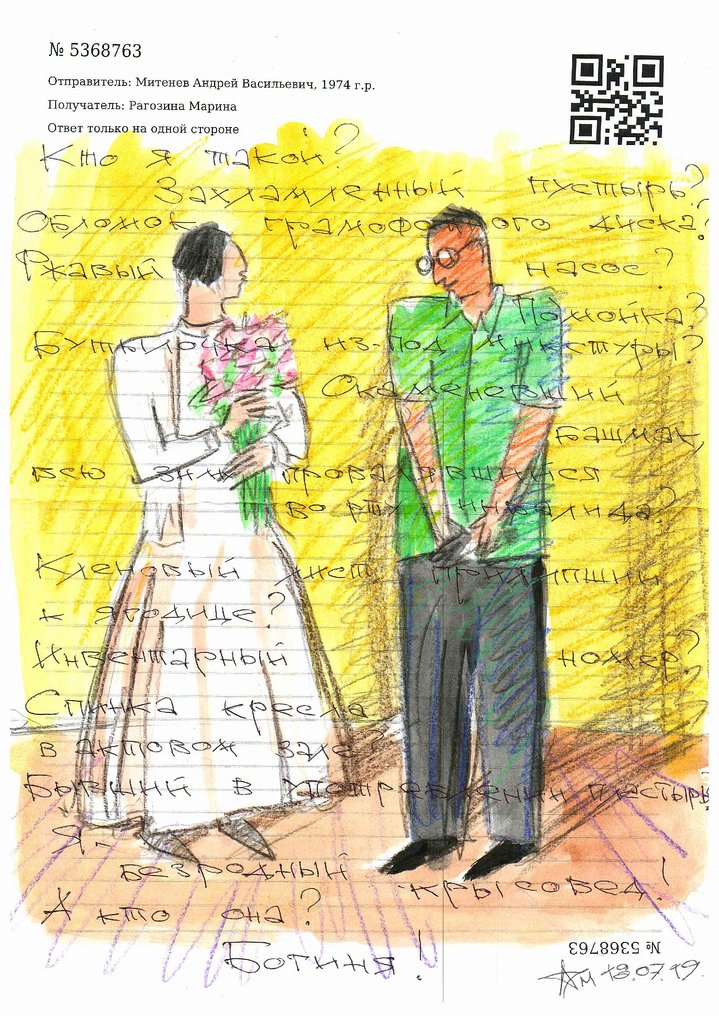

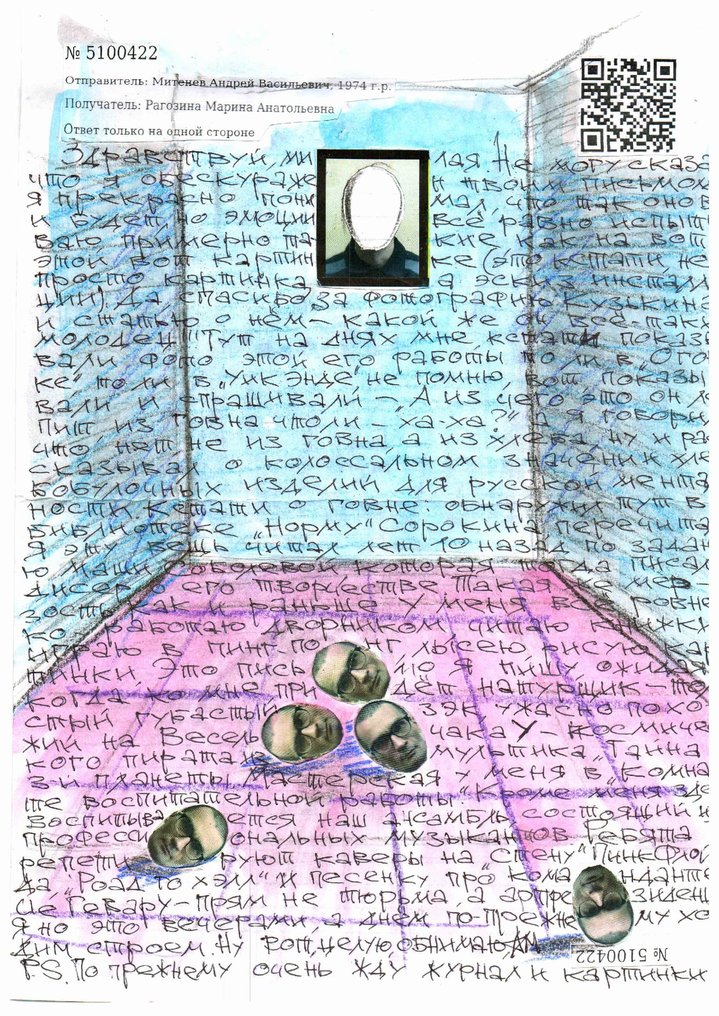

It has not become easier for Russian prisoners to share their stories. Today’s Federal Penitentiary Service’s rules on correspondence for inmates are strict, meaning that few narratives see the light of day before their creators themselves do. Those who are especially daring find ways around their restrictions on communication, elaborately and colourfully illustrating their letters home, like Andrey Mitenyov, or trying their hand at the ancient medium of prison tattoos like Oleg Navalny (brother of the Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny). The lengths to which they stretch the boundaries of the artistic forms available to them can now be seen the world over, and their stories will not be lost.