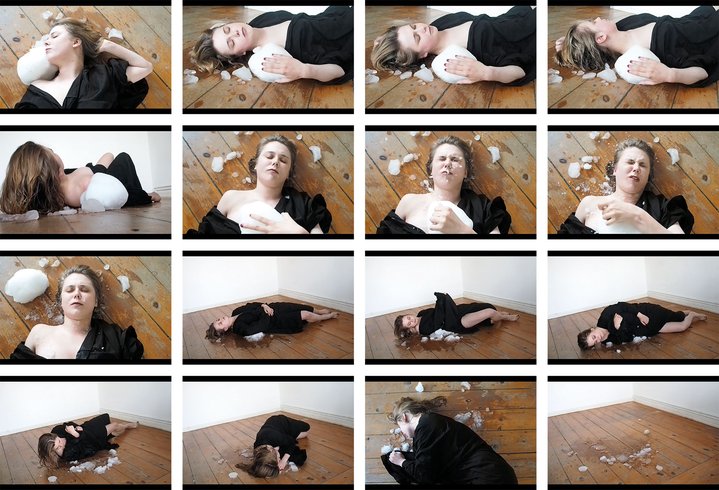

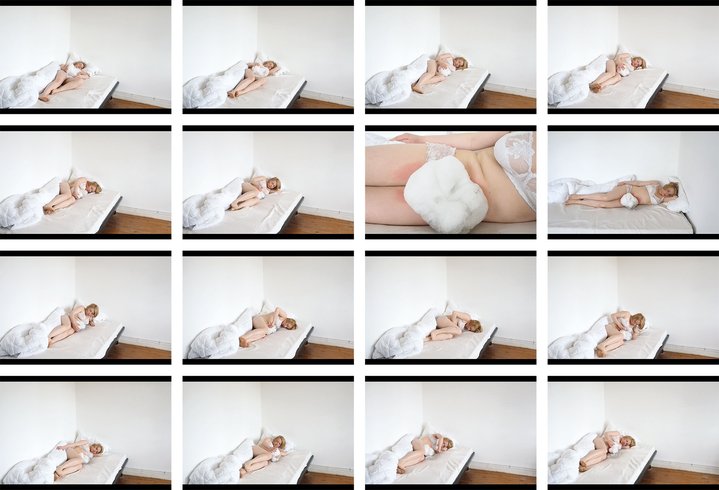

Daria. Love is not for sale. 'And What About Love?' exhibition, 2015. Photo Anton Khlabov

Where is russian feminist art heading?

An exhibition of two female art collectives, DVR and Gentle Women, opens at PERMM Museum of Contemporary art. But they are not the only artists today who are concerned by the rights and visibility of women in Russia.

Despite their geographical distance from one another, two Russian art groups, DVR - an acronym for ‘Dalnevostochnyye razluchnitsy’ (in English “The Far Eastern Homebreakers”) - based in Primorsky Krai in the Far East of Russia, and ‘Nezhniye Babi’ (in English “Gentle Women”) from Kaliningrad, Russia’s westernmost region, will meet at the PERMM Museum to exhibt new works specially created for the show. Alisa Savitskaya, the curator of the exhibition ‘She Was as Beautiful as a Russian Landscape’ concedes that it is not purely a feminist project, however DVR envisions “a future with no gender borders or subordination” and Nezhniye Babi demonstrate “women’s absolute rights”. The show urges us to take stock and think about what is new in the minds of Russian feminist artists over recent years.

Looking back to 2010, the exhibition ŽEN d'ART at MMOMA, curated by Natalia Kamenetskaya and Oksana Sarkisian, summed up representation of gender in post-Soviet art over the previous two decades. The following year, punk band Pussy Riot released their first song with the poignant title ‘Kill the Sexist’, predating the #metoo movement by six years, yet, it was a time when feminism in Russia was far from mainstream.

Pussy Riot’s ‘Punk Prayer’ in 2012 was in many ways a definitive turning point. According to Moscow based artist historian and researcher Angelina Lucento, what they did and stood for can be seen as “an inevitable reaction to forms of brutal masculinity that dominated Moscow Actionism in the 1990s” and not only to the patriarchal structure of Russian society and power. Lucento concludes that Pussy Riot was looking to create a different quality of power, more associated with “maternity and femininity than virility”. And it is for this reason the members of the band addressed the Virgin Mary: they were literally begging her to become a feminist.

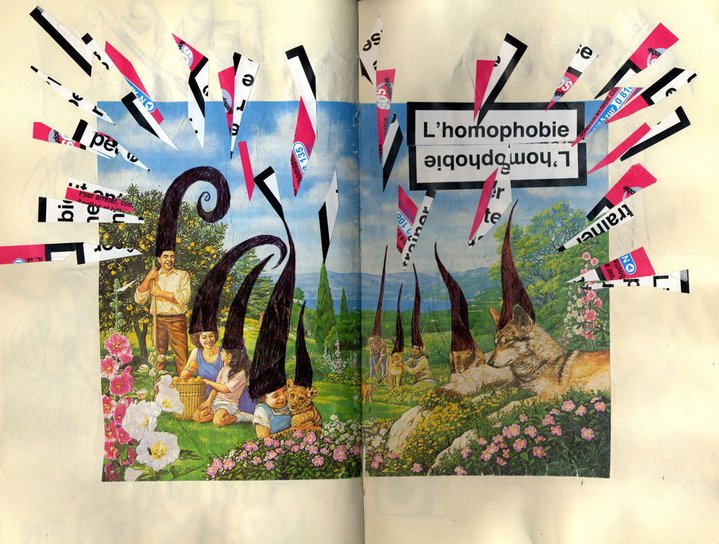

From 2012-2015, two parallel processes emerged: firstly, an ethical and socially tuned art activism, which threw out the heroic figure of the artist and moved towards more horizontal interactions with others. And secondly, there was a boom in new feminist art projects and exhibitions. There was the 2013 ‘Feminist Kitchen’ project curated by Oksana Sarkisyan and Victoria Begalskaya; a series of exhibitions and projects: ‘Feminist pencil’ curated by Victoria Lomasko and Nadya Plungian between 2012 and 2015; ‘The Kitchen’ and ‘A for Art, F for Feminism’ by Marina Vinnik and Mikaela, as well as group shows ‘And What About Love?’ (2015) curated by Anastasia Vepreva, Anna Tereshkina, and Polina Zaslavskaya. They were elaborating their own language and aesthetics, creating a space for self-reflection and emancipatory practices. Mostly, these initiatives were not hosted by museums or galleries, but by organizations with a human rights agenda, such as the Sakharov Centre (recognised as foreign agent by the Russian authorities) in Moscow, or the House of Equality in Murmansk. Some criticized them for showing a lack of quality over the selection criteria of participants, while others felt that an overly academic language alienated the artists from their real experiences.

The core of these shows, however, was the idea of art as both an emancipatory practice and a means of self-advocacy. They were about encouraging people to express their own female experience and to help others speak out through art. So, for the creators of the ‘Feminist Pencil’, the participants’ desire to be heard was more important than their professional standing and the curators of ‘Feminist Kitchen’ decided to collaborate with sex workers. Often ridiculed by both high brow art critics and the media alike and out of favour with art institutions, it was as if feminist artists took up the invisible work that women are so used to doing.

As a result, against a background of increasing repression in their homeland, specifically the decriminalization of domestic violence in 2017 and the risk of being declared a foreign agent introduced in 2021, a growing and significant number of small media (zines, Telegram channels and podcasts) has emerged, where feminist artists discuss common topics and critically analyze each other’s work. As Holland Cotter rightly observes, “one of feminism’s great strengths has been a capacity for self-criticism and self-correction.” But, at the same time, it provokes a great number of heated debates within the community. Many artists are profoundly engaged in social work and care. Daria Apakhonchich (b. 1985, recognised as foreign agent by the Russian authorities) was teaching Russian to migrants and lost her job at the Red Cross, due to being included on the state list of “foreign agents”, which put her under constant state audits and the risk of unemployment. Daria Serenko (b. 1993, ‘Quiet Picket’, ‘Extraordinary Communication’) created an online course on feminism, activism and gender and co-organized the ‘Femdacha’ project, a country retreat for burnt out activists. Katrin Nenasheva (b. 1994, ‘Don’t be Afraid’, ‘Punishment’) regularly cooperates with psycho-neurological and teenage support centres. Their social work is so tightly bound with their artistic work that, for many people, their artistic projects are often mixed up with social projects of other activists. This is how Time Magazine illustrated an article about Anna Rivina, head of the centre Nasiliu.net (organisation recognised as foreign agent by the Russian authorities), with an uncaptioned photo of the art action ‘Quarrel With Me’ by Katrin Nenasheva, that has nothing to do with this centre.

Being rejected by institutions, feminist artists didn’t wait long to self-organize and create their own. FemInfoteka, a DIY feminist and queer library in St. Petersburg has been collecting and sharing feminist books, art catalogues and zines since 2016. The feminist publishing house NoKiddingPress, which grew out of a blog, publishes the work of both Western and Russian artists. The cultural and music festivals LaDIYfest (2016), Moscow Fem Fest (2017-2021) and the Festival of feminist writing (2021) work closely with women artists.

The growth of micro media has developed an entire new field of media feminist activism. Media strike #forYulia in defense of artist and activist Yulia Tsvetkova (b.1993) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) from Komsomolsk-on-Amur, who was accused of producing pornographic material, became an unprecedented act of solidarity. Artistic performances such as Vulva-ballet by Darua Apakhonchich (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) in solidarity with Tsvetkova expanded the support offline. Feminist illustration is another trend that has grown over the last few years: from Victoria Lomasko’s (b. 1978) invisible portraits of women and graphic reports; illustrations by Nixel Pixel (Nika Vodvud, b.1993) for social projects, to everyday-life illustrated self-reflective documentation by Masha Katarsis (b. 1997). Some artists focus more on their national identity and roots, body, rituals and their relations with nature. Alisa Gorshenina (b. 1994) explores traditions of her native Urals and other regions. Taus Makhacheva (b. 1983) inscribes female heroism into everyday life in Dagestan with her alter ego ‘Super Taus’.

Being rejected by institutions, feminist artists didn’t wait long to self-organize and create their own. FemInfoteka, a DIY feminist and queer library in St. Petersburg has been collecting and sharing feminist books, art catalogues and zines since 2016. The feminist publishing house NoKiddingPress, which grew out of a blog, publishes the work of both Western and Russian artists. The cultural and music festivals LaDIYfest (2016), Moscow Fem Fest (2017-2021) and the Festival of feminist writing (2021) work closely with women artists.

The growth of micro media has developed an entire new field of media feminist activism. Media strike #forYulia in defense of artist and activist Yulia Tsvetkova (b.1993) from Komsomolsk-on-Amur, who was accused of producing pornographic material, became an unprecedented act of solidarity. Artistic performances such as Vulva-ballet by Apakhonchich in solidarity with Tsvetkova expanded the support offline. Feminist illustration is another trend that has grown over the last few years: from Victoria Lomasko’s (b. 1978) invisible portraits of women and graphic reports; illustrations by Nixel Pixel (Nika Vodvud, b.1993) for social projects, to everyday-life illustrated self-reflective documentation by Masha Katarsis (b. 1997). Some artists focus more on their national identity and roots, body, rituals and their relations with nature. Alisa Gorshenina (b. 1994) explores traditions of her native Urals and other regions. Taus Makhacheva (b. 1983) inscribes female heroism into everyday life in Dagestan with her alter ego ‘Super Taus’.

Many artists are re-evaluating traditionally female crafts like a renowned group ‘The Factory of Found Clothes’ (1995-2014) by Gluklya (b.1969) and Tsaplya (b.1968). Their followers, the creative union ‘Nadenka’ (founded in 2014) list collectivity, tenderness and sisterhood among their main interests. The co-operative ‘Stitches’ (in Russian ‘Swe-my’) was created a year later in 2015 by members of ‘What is to be done?’ (‘Chto Delat?’). Their workshops on re-stitching old clothes have been included in art biennales. They've created costumes for the theatre performance ‘The Vagina Monologues’ and a collection of queer-feminist skirts. Anya Popova (b. 1996) chose the setting of a jewelry shop for her long-term ‘Project 1406’, which is “aimed at changing society through the destigmatisation of the body”. Among the items on sale there were earrings in the shape of letters ‘N’ and ‘O’: “To me, N O is a story about many things. It’s about amendments and about the need for active consent,” the artist explains.

It goes without saying that not all female artists in Russia are, of course, feminists. Many pay only partial attention to feminist issues, as they do not want to attract labels. Thus, Julia Aleshicheva (b. 1938) creates embroideries about women. Her works, ‘The Girl Who Loved But Never Married’, ‘The Girl Who Could Not Remember’, were recently exhibited at the Sevkabel in St. Petersburg. However, Aleshicheva does not know if she is a feminist. She doesn’t know even if she’s an artist at all, because she suffers from dementia. Her work is carefully preserved and exhibited by her grandson.

Today, Russian feminist art oscillates between two poles: the furious struggle of punk prayer with its extraordinary media coverage and the daily work of quiet pickets and discrete apartment exhibitions. Let’s see which strategy wins out.

She Was as Beautiful as a Russian Landscape

Perm Museum of Contemporary Art (PERMM)

Perm, Russia

February 18 – April 17, 2022