Tarusa: the inner sanctum of the soul

The small Russian provincial town of Tarusa became a haven for artists and managed to retain its magnetism for a century and a half, overcoming wars, revolutions, changing political tides and artistic vogues.

“I emigrated from Moscow to Tarusa via Paris. In fact, I migrated to the inner sanctum of my soul long ago.” (Eduard Steinberg)

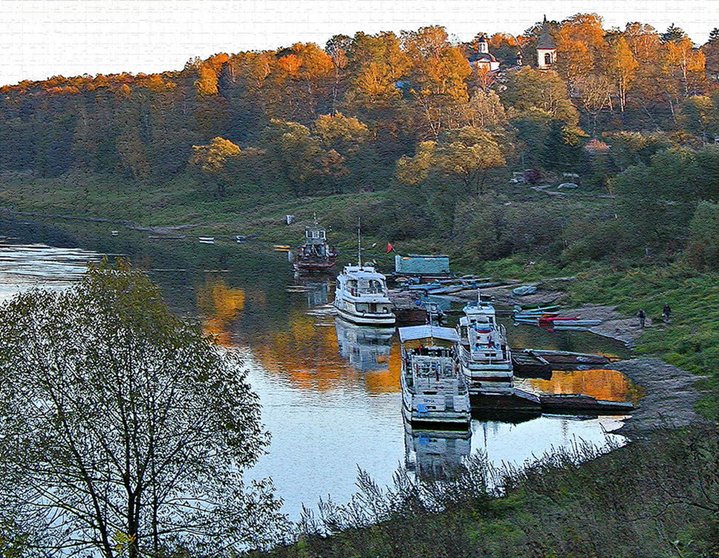

There are magnetic places on earth that offer more than just breathtaking sights. The small Russian town of Tarusa standing on a high bank above the Oka River 140 km to the south of Moscow is one such shelter.

Tarusa started attracting artists and writers in the late 19th century. “Perhaps, nowhere near Moscow could one find places looking so typically and touchingly Russian,” was the way 20th century writer Konstantin Paustovsky (1892--1968) described his beloved retreat, comparing it to Barbizon, which, in the 19th century, attracted artists to that village near Paris.

It all started when the already well-established painter Vasily Polenov (1844–1927) bought a large chunk of land near Tarusa a quarter of a century before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and planted trees along the Oka, transforming what had been empty fields into a very romantic and shady oasis. His goal was to turn it into an artists’ commune. The estate, named Polenovo, was nationalized by Stalin after the founder’s death, but the family was exceptionally allowed to remain there.

What greatly contributed to turning Tarusa into a thriving artists’ commune was Stalin’s decision after the end of World War II to force many supposedly unreliable intellectuals into internal exile. That policy was also ferociously applied on a huge army of crippled wartime veterans. It was known as the 101 km rule, the minimum distance these exiles had to live from Moscow.

As the childen of those exiled intellectuals grew up, a new generation of dissidents took shelter in Tarusa. It was there that the future Nobel Literature prizewinner Iosif Brodsky (1940–1996) lived while waiting for permission to leave the Soviet Union, which was finally granted in 1972.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), another exile and winner of that same Nobel prize, often visited Tarusa. Pianist Svyatoslav Richter, one of the first collectors of independent Soviet art, built a house in the town’s vicinity.

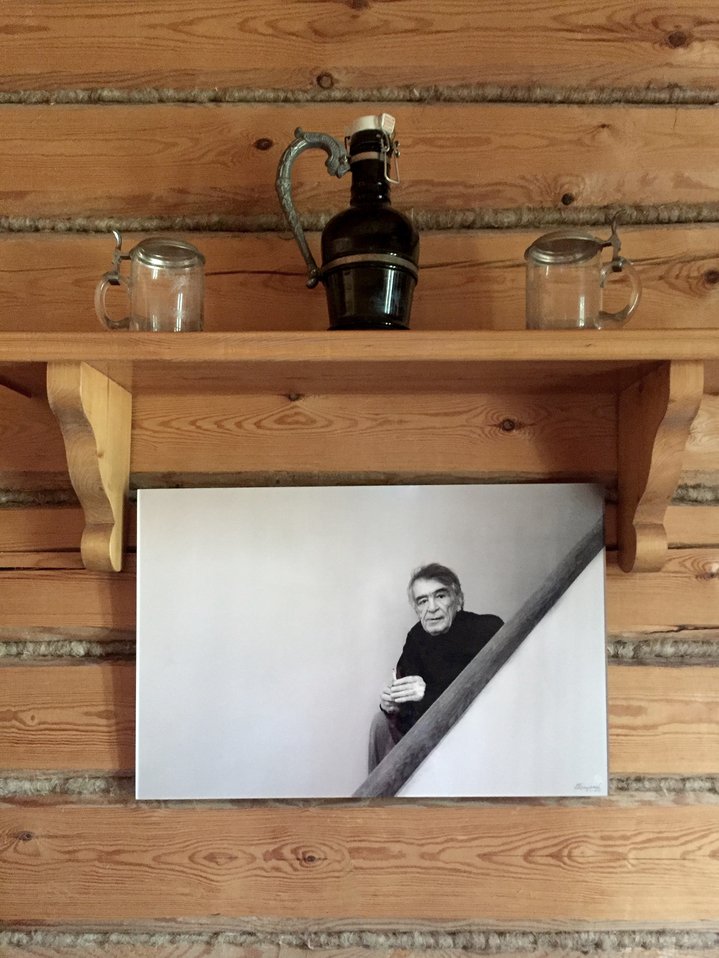

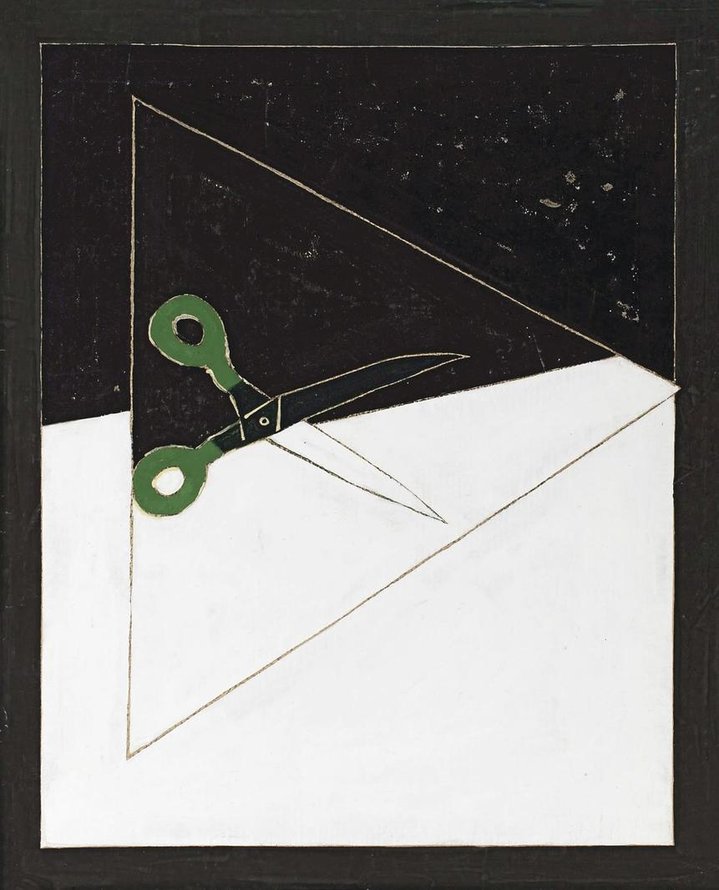

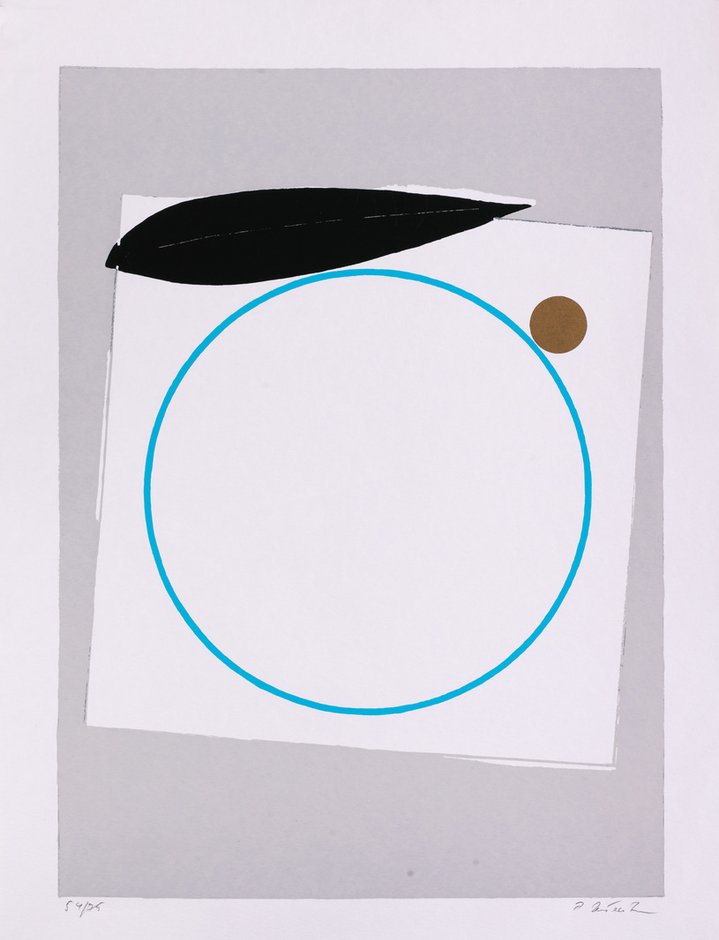

“I emigrated from Moscow to Tarusa via Paris,” said Eduard Steinberg (1937–2012), a Russian nonconformist in one of his interviews. The artist, who was part of the second wave of the Russian Avant-Garde, became famous outside Russia. He studied drawing and arts from his father Arkady, a political dissident, poet, translator and artist. For his son Eduard, the traditions of Russian the Avant-Garde were not only a chapter in the history of arts, but a family tradition handed down like a secret knowledge from father to son.

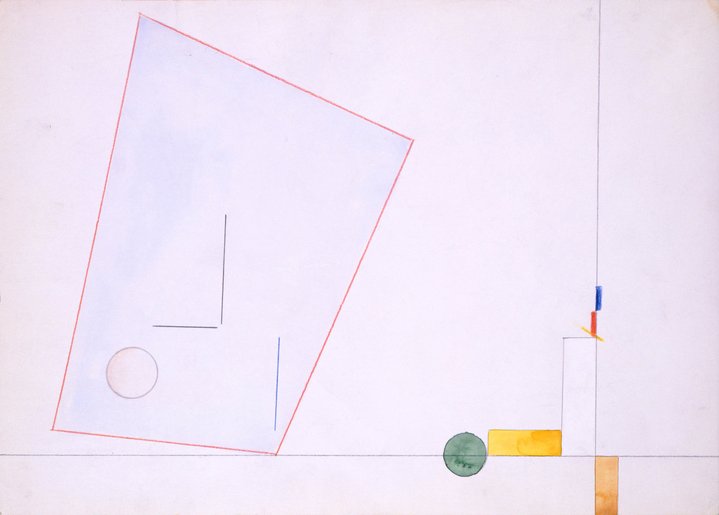

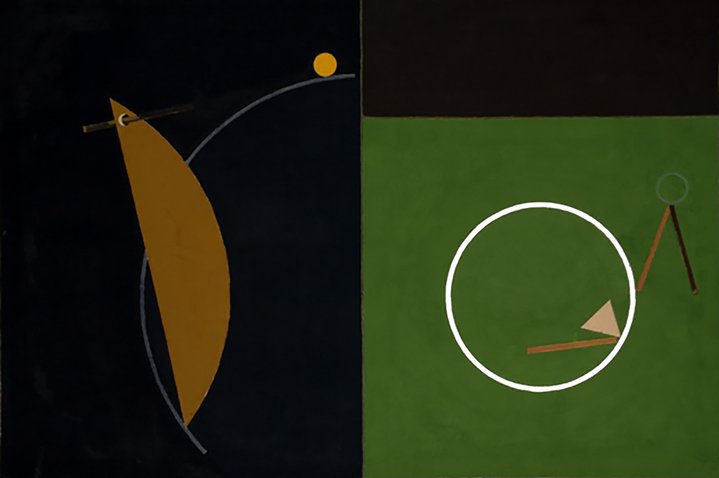

The Russian Avant-Garde that was completely erased from the history of art in Soviet times. This partially explains why Eduard Steinberg could produce Suprematist abstraction in the 1970s without feeling at all out of date.

Having finished public school in Tarusa, the artist had to spend his youth taking odd jobs. In 1961, one of the first unofficial art exhibitions in Soviet history took place at the Tarusa House of Culture, which, apart from the paintings of Steinberg, featured the works of Mikhail Grobman (b. 1939), Vladimir Yakovlev (1934–1998), Mikhail Odnoralov (1944–2016) and other “leftist” artists.

In 1962, Eduard Steinberg’s first personal exhibition took place in Tarusa and with it came the Soviet Underground’s acclaim. Steinberg soon became a member of the Sretensky Boulevard art association, the most advanced art group of those years, led by the artist Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933). He started working in Paris in 1988, where he collaborated with the Claude Bernard Gallery for many years. However, he did not emigrate. He always spent half of the year in Tarusa and the other in Paris. “Tarusa is my home,” he used to say. He died in Paris, but was buried in Tarusa. His severe and very pure abstractions hang on the walls of his simple cottage, surrounded by orchards in a quiet street. It has since 2017 become an annex of Moscow’s Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts.

Steinberg attracted a whole constellation of unofficial artists to Tarusa, including Dmitry Plavinsky (1937–2012), Anatoly Zverev (1931–1986), Alexander Kharitonov (1932–1993), Boris Sveshnikov (1927–1998) and many others.

Plavinsky, a Russian artist and illustrator, one of the key figures of the Moscow art underground and the creator of his own symbolic philosophy, wrote of that house in his memoirs: “The room was so filled with the bluish cigarette smoke that we could hardly recognize each other. Spengler, Kierkegaard, Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre – over the chasms separating these personalities, bridges of associations were built, forming a single mushroom cloud of thought… We often lingered until morning. I could not imagine my life without Tarusa anymore, so I decided to find a large room for the winter, bright enough for work.”

Plavinsky brought his comrades, artists Anatoly Zverev and Alexander Kharitonov, to Tarusa. Zverev had to produce a large number of works for his personal exhibition in Paris, and as soon as possible, so they stocked up paints, paper and canvas and started to work together.

“Zverev worked swiftly. Armed with a shaving brush, a table knife, gouache and watercolours, he threw himself at a sheet of paper with a jar and doused the paper, floor, chairs with dirty water, throwing buckets of gouache into the puddle. He then smeared this nightmare with a rag or even with his own shoes and then scratched two or three lines with a knife. The unexpected result was a fragrant bouquet of lilacs, or a church, or an old woman’s face,” Plavinsky recalled.

Zverev became a landmark of Russian unofficial art, not because of his social protests, but because he demonstrated freedom in the way he lived. He turned his very life into art and into an endless performance.

This idyll ended sadly and abruptly during a fight between Moscow artists and local hooligans. According to some reports, what caused it was Zverev pinching a barmaid’s bottom. Others say the fight began because he won a game of checkers played with a man who hated losing. Zverev was so brutally beaten that he only came round in a Moscow intensive care unit.