Russia’s Private Art Institutions Celebrate Metaphysical Art

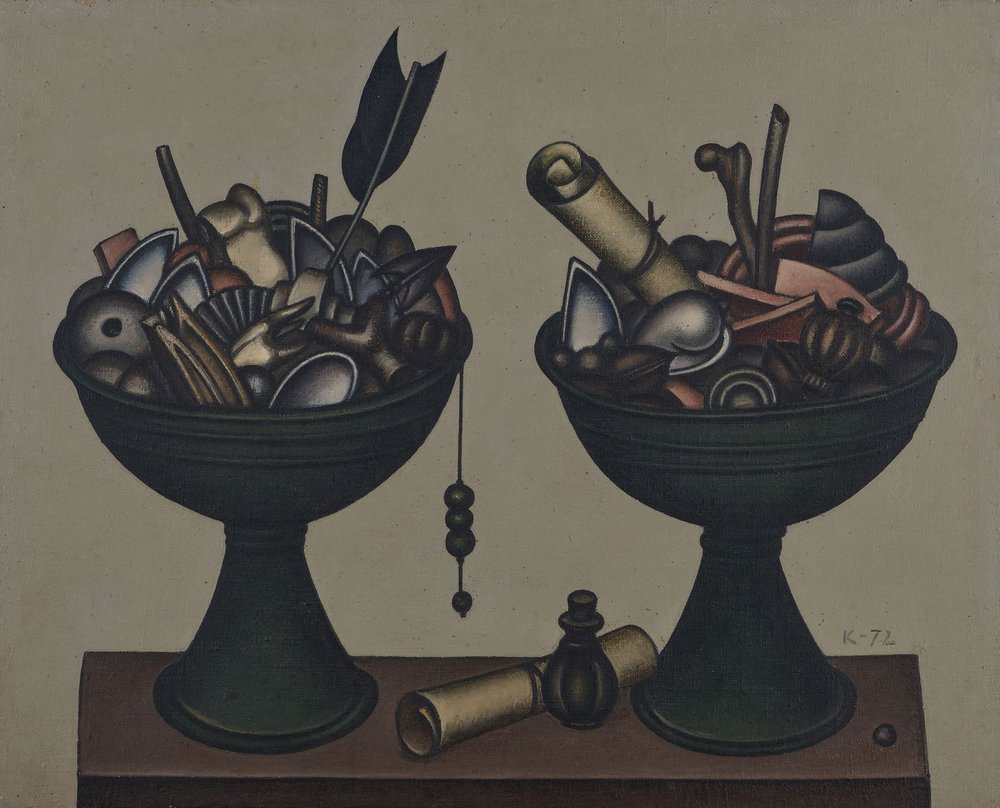

Dmitry Krasnopevtsev. Two green bowls with objects, 1972. From Prometheus Foundation's collection. Courtesy of AZ Museum

Three concurrent exhibitions in Moscow and St Petersburg draw our attention to a spiritual dimension in the art of the Soviet non-conformists. When the times are out of joint, can metaphysics be a cure?

The strong metaphysical trend in the art of the non-conformists is already a well-known and well-studied phenomenon. However, this aspect of art history, which for many years was only of niche interest to academics and artists, has now entered the public consciousness. The question of how to present this esoteric, meditative art to today’s adrenaline-hungry audiences with ever-shorter attention spans has no simple answer; curators are responding to this challenge in a variety of ways.

The highlight of this impromptu metaphysical jamboree is a huge, museum-quality exhibition curated by Anna Romanova at the Ekaterina Foundation in Moscow. Based on loans from over two dozen private collections, it features works primarily from the collections of Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin, as well as the Prometheus Foundation in St. Petersburg. In a sophisticated, succinct way, it highlights key themes in artists’ spiritual exploration: the symbolism of light and darkness in the paintings of Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013) and Erik Bulatov (b. 1933); Dmitry Krasnopevtsev’s (1925–1995) inventive interpretation of the vanitas subgenre of still life; and the disembodiment of objects in the almost monochromatic paintings of Vladimir Weisberg (1924–1985). The works of art are grouped in such a way as to highlight numerous subtle, barely perceptible visual connections. The curator builds imaginary bridges, for example, between Eduard Steinberg’s (1922–1986) ‘metageometry’ and semi-abstract canvasses by Viktor Pivovarov (born 1937). Vladimir Nemukhin’s (1925–2016) sculptures, dedicated to Steinberg and Krasnopevtsev, are strategically placed to complement their paintings. This exhibition bucks current trends: there are no long-winded labels with biographical details, eye-catching exhibition design elements, or digital special effects, the focus is on the artworks themselves, rather than their context. There are two halls dedicated to Krasnopevtsev and to Steinberg, while Vassiliev and Bulatov share another. Rather than avoiding monotony, the curator embraces it, hand-picking similar works from many different collections to create a sense of continuity, emphasize subtle differences, and highlight visual similarities which might otherwise not be obvious to the viewer.

The exhibition transports visitors into a state of trance-like meditation. As you wander through the space, you move deeper into the illusion of ascending an ivory tower where the underground artists ignored the harsh and ugly Soviet reality around them and immersed themselves in aesthetic and philosophical problems, yearning for solid truth and eternal beauty. Of course, the reality was very different. The artists of this generation came of age during Khrushchev’s Thaw, when the crimes of Stalin’s regime were openly admitted for the first time. “After the 20th Communist Party Congress, [where the ‘personality cult’ of Stalin was first admitted – Ed.], people were totally lost and did not know how to carry on. Bulatov and Vassiliev did not even sign their early works because they were confused and unhappy about what they were doing”, the curator told Art Focus Now. However, she carefully avoids the socio-political context, choosing a more generalised, philosophical approach. The exhibition focuses on the artistic and mental crossroads where the non-conformists found themselves. It demonstrates how their spiritual pursuits and visual experimentation were intertwined, showcasing the symbolic rethinking of still life and landscape, wanderings between figuration and abstraction, an uneasy relationship with the rediscovered heritage of the avant-garde and a keen interest in ancient religious traditions, ranging from Eastern to Christian mysticism (although, of the artists presented here, only Steinberg converted to Christianity). The non-conformists’ paintings are interspersed with works by contemporary artists who, while not sharing the same aesthetic, exhibit a similar yearning for purity and integrity. Examples include the iconic and mesmerizing black-and-white animated video ‘The Lake’ by the Blue Soup group, the geometrical abstraction in motion by multimedia artist Platon Infante (b. 1978), and star-studded skies painted by Alexandra Paperno (b. 1978). In times of chaos and uncertainty, it seems that the quest for the Absolute becomes increasingly common. “The contrast between light and darkness is highly relevant today,” says Romanova.

The independent AZ Museum has taken an alternative curatorial approach to celebrate Dmitry Krasnopevtsev’s centenary with a solo exhibition in its new AZ/ART space. The exhibition reveals how his otherworldly and cryptic art was rooted in reality and time. The artworks on display also come from private collections, primarily that of Natalia Opaleva, the founder of AZ, as well as the Prometheus Foundation. Titled ‘The Balance of the Unbalanced’, the exhibition begins with Krasnopevtsev’s early, traditional Flemish-style still lifes and progresses to his instantly recognizable signature pieces. The artist is renowned for his meticulously balanced compositions of assorted junk, including broken ceramic vessels, pottery shards, shells, stones, ropes, and sticks. These are painted in subdued, earthy tones on sheets of hardboard. Curator Natalia Volkova likens him to an alchemist in search of the Philosopher’s Stone. The exhibition attempts to explain how this magic was created. Documents, magazine exhibition reviews and artefacts from the artist’s studio are displayed in large glass-covered niches designed by artist and curator Katya Bochavar. There is even a soundtrack: Krasnopevtsev’s diaries read aloud by an actor. Here, the context competes with the artworks for visitors’ attention and often wins. Is the meditative silence of Krasnopevtsev’s airless world too profound for today’s audience?

Most of the non-conformists featured in these exhibitions have long since passed away. Yet those who are still alive remain true to the same lines of thought. Commissioned by A Room and a Half, the private museum of the late poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996), Viktor Pivovarov illustrated the poet’s famous piece ‘Speech over Spilled Milk’ (1967). This album is the first in the museum's recently launched series of limited-edition artists’ books based on Brodsky’s most famous literary works. In this poem, 26-year-old Brodsky laments the lack of money and prospects in the Soviet Union, where poets who do not produce material wealth are ostracized by society. In his drawings, the octogenarian artist eliminates mundane details that make the young man’s lament disturbingly realistic. Pivovarov evokes images from his early career: human and geometrical figures inspired by de Chirico’s work. The destitute lyrical hero of the poem is transformed into a symbolic being, an Eidos. Rather than focusing on the personal trials and tribulations of a young poet, the artist considers the futility of human actions in general. The album, printed in an edition of 58, is now on display in the exhibition at ‘A Room and a Half’.

Reason and Sentiment

Moscow, Russia

10 September – 16 November 2025

Pivovarov-Brodsky. Speech over Spilled Milk

A Room And a Half Museum, Flat 7 exhibition space

St. Petersburg, Russia

7 September – 15 October

Krasnopevtsev. The Balance of the Unbalanced

Moscow, Russia

25 September 2025 – 8 January 2026