Russian Herstory as an Animated Cartoon

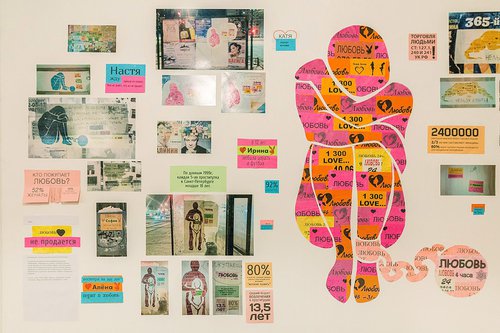

I’m Coming to Look for You. Exhibition view. Krasnoyarsk, 2024. Photo by Alena Rotenberg. Courtesy of Ploschad Mira Museum Centre

Two female artists from different generations are reconstructing Russian history from authentic narratives harvested from personal stories and family heirlooms and have found a receptive audience among Russians across the nation who have discovered a new taste for exploring their own origins.

Over the past five years artist Natasha Shalina (b. 1966) scoured flea markets, across numerous countries, to put together a collection of over two hundred vintage objects which she has now assembled in her latest installation work, ‘I’m Coming to Look for You’ currently on view in Krasnoyarsk at the Ploschad Mira Museum Centre, a multi-media work which combines painting, video and audio together with these found objects. There is also a collage made out of old wedding photos from the late 19th century to the 1980s that she found by advertising on social media. Among these photos is an image of newlyweds from Siberia and when the couple found out that Shalina had chosen to include their photograph, their entire family of six bought tickets from Omsk to Krasnoyarsk to attend the exhibition.

For Shalina archive photographs, antique lace, vintage dresses, headdresses and bridal veils may be the material of her artistic statements yet they are destroyed at the end of the exhibition because as a matter of principle Shalina does not keep any of the artefacts she uses in her artworks. Conversely, for artist Yulia Andreeva (b. 1996) folk costumes have the ultimate cultural value as objects of memory and museification as seen in her project ‘Reflections of Tikhmanga’ in the Kargopol Historical, Architectural and Art Museum.

By chance, both artists have shows on concurrently, Shalina’s in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk and Andreeva’s in Kargopol in the North-West of Russia, and despite the geographical distance between the two, they have much in common. Both explore and attempt to understand individual destinies in Russian history, or as Shalina puts it “genetic family trauma.” While in Krasnoyarsk Natasha Shalina’s artistic statement is the culmination of several years work where she looks for historical material to fit her theme, in Kargopol Andreeva and her curator took a collection of folk costumes as their starting point which they then went on to research, the fruits of which are the current exhibition.

It seems that both exhibitions tap into something latent among the public, a growing collective yet individual need to explore one’s own origins. Yulia Andreeva is a third-generation artisan from Kargopol who makes folk toys and during the exhibition she has been holding masterclasses where she teaches various techniques of painting on wood and collage using different materials and objects. The participants in her masterclasses fully embraced the script, visiting the museum again and again, writing Andreeva personal letters and continuing their own creative searches, further developing the works they made during the masterclass, and telling stories about their own families. Shalina and Andreeva both feel a deep need to help other women reconstruct, record and document their own family histories.

In 2018 British sociologist Elisabeth Schimpfossl published ‘Rich Russians: from Oligarchs to Bourgeoisie’ compiled from interviews with numerous ultra high net worth Russians and she identified a trend. Their success could be explained by genetics and their origins were often to be found in the Soviet intelligentsia and nomenklatura, widely considered to be ‘good families’. Today in Russia, interest in understanding one’s origins is no longer just the preserve of the über wealthy, there is a growing desire among people everywhere to study and understand their family background. In the small Northern Russian town of Vologda a museum called ‘House with Stuff’ opened last year in a pre-revolutionary era wooden house packed to the rafters with vintage antiques and Soviet household items, old photographs from the 1920s depicting the inhabitants of communal flats after the nationalisation of private housing after the Bolshevik Revolution and until the late 1980s, when the authorities finally gave them their own flats in another part of the city. “People from Vologda enthusiastically brought in photographs of the house” says the guide, “Working class descendents from the same families who lived in Vologda before the revolution are still living in our city today. Everyone wants to tell their own story”.

The Kargopol exhibition ‘In the Reflection of Tikhmanga’ was the result of researcher Ekaterina Perova’s indepth study of Kargopol Museum’s holdings. “In 2008, the museum acquired more than thirty pieces of clothing including a tablecloth and curtains from the dowry of a peasant woman who lived in Kargopol at the beginning of the 20th century”, says Perova. “We were thinking about how best to present it and we did a lot of study in the archives”. We discovered that it had been the dowry of Maria Mikhailovna Artyomova who came from the village of Tikhmanga on the Tikhmanga River in Kargopol region, and whose story was written down in 1977 by one of her neighbours in notebooks which were handed over to the museum by a local historian Gennady Durasov. The main body of memories are stories about childhood, family life, and the life of the fishing village where Maria was born in 1906. She got married in 1925, the wedding ceremony took place in the church in Tikhmanga. “I had a big dowry. Thirty-two pairs and sundresses,” Maria Mikhailovna recalls in her story. “Thirty-two pairs mean a blouse and a skirt,” explains Ekaterina Perova. The marriage went on to last all but six months and her father, who had forced her to marry in the first place, took Maria back home. According to old Kargopol tradition which dates back to the 18th century, a wife’s dowry (which might include valuable, pearl-embroidered kokoshniks and golden headscarves) remained as her property and did not pass into the ownership of her family and husband so Maria fought for the return of her dowry and spent many years suing her ex-husband. She left her hometown travelling to Leningrad, where finally she married for love and in 1939, she gave birth to a daughter. But in the early days of World War II, having said goodbye to her husband who went to the front, Maria Artyomova returned to her parents’ house in Tikhmanga.

In 1990 brief excerpts from the memoirs of a daugther of Moldavian landowners were published in the form of a comic strip in Ogonyok magazine which became an overnight sensation across Russia, ‘The Life of Efrosinia Kersnovskaya’, who was imprisoned in a Gulag in Norilsk and Mikhailova’s story strikes a similar note as an engaging authentic historical account written down from a female and personal perspective. St Petersburg exhibition designer Yuri Suchkov was impressed by the well-preserved folk costumes that had been sitting for a century in the attic of the house in Tikhmanga, and having heard Maria Artyomova's story, suggested the curators model the exhibition on the Kersnovskaya chronicle in Ogonyok and draw Artyomova’s life story in the style of a comic book. Yulia Andreeva’s ten acrylic on wood paintings depict the most dramatic episodes from Artyomova’s diary. During her preparation for the exhibition Andreeva travelled to the village several times, she looked at the bridge over the river where young peasants used to party and socialise, at the fishermen, whose trade has changed little over a hundred years and at the social structure of the village. It has inspired Andreeva herself to restore the history of her own family, studying the generations of folk artists of Kargopol region on her mother’s side.

In the end, for Krasnoyarsk-born Natasha Shalina who now lives in St Petersburg her project ‘I'm Going to Look for You’ is a path towards her own self, an attempt to accept herself, her biographical and biological transformation. “As an adolescent girl, a woman is constantly experiencing crises of transformation and change and a coming-to-terms with each new period of her life,” says the artist. And at the same time, it is an acceptance of her ancestry, the history of one family that endured Stalin’s repressions, that were evicted to the north of Krasnoyarsky Krai, who saw shootings, experienced famine, her “genetic trauma,” Shalina says. “When the curator proposes that I go through my exhibition once again, I experience fear,” says the artist, “I have already lived through it once before”.

I’m Coming to Look for You. Natasha Shalina

Krasnoyarsk, Russia

21 March – 28 July, 2024

In the Reflection of Tikhmanga

Kargopol, Arkhangelsk region, Russia

12 May – 31 December, 2024