Russian Artists Searching for a New Identity in Georgia

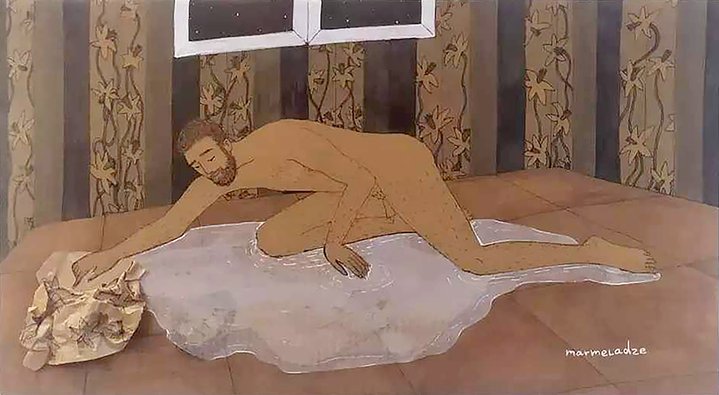

Alisa Yoffe. Bodies #4, 2022. Acrylic on canvas. 320x148 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Over the past year numerous Russian artists have found refuge in Georgia. Moscow curator and art historian Katerina Jurbina moved to Tbilisi with the recent wave of Russian emigrés and she explores how they are trying to reinvent themselves in their adopted homeland.

Since the 19th century Georgia - or as the locals call it, Sakartvelo - has inspired many Russian-speaking artists. After the 1917 Revolution it became a haven for artists and this left its mark on Georgia’s cultural life. Despite the arrival and imposition of the academic traditions of Socialist Realism in the 20th century, there was always a place for free art, which you see clearly in Georgian art of the second half of the 20th century.

Georgia’s domestic art market may be limited in size with works selling at a far lower price range than in Russia, but it is very active. There are a lot of wealthy collectors and galleries supporting national artists and giving them a helping hand onto the world stage. Since the conflict they have been collaborating with Ukrainian artists.

When it comes to cancelling Russian culture, although this impulse is not felt so keenly in Georgia where many people speak Russian, exhibiting Russian expatriate artists in major galleries or even public spaces does bring with it some difficulties. After the conflict began, Sakartvelo was swamped by émigrés not only from the cultural sector, attracted by the favorable conditions which enable Russians to stay up to a year without a visa. Now a year on, many have left, however some are putting down roots, building a new sense of self-perception, with hopes and plans for the future.

Alisa Yoffe and Xanax Tbilisi

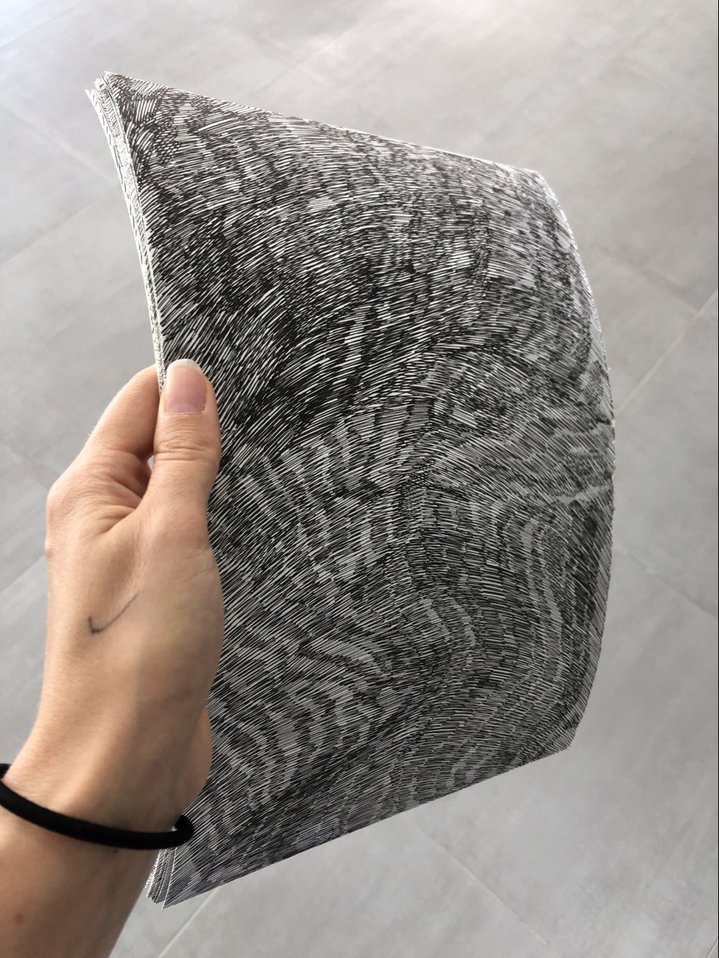

Her huge studio is hidden in the womb of a 1970s Soviet modernist building, like a pearl in a beautiful, fossilized shell. Tall windows, a concrete floor, bare grey walls and Alisa Yoffe's (b. 1987) large-scale white-and-black pictures in an empty and seemingly no longer-empty space. She has been working here for almost a year, taking part in exhibitions, events and residency projects in Georgia and Europe, preparing a joint VR project Xanax Tbilisi with Arseny Morozov, a musician from St Petersburg, and Andrei Aranovitch, a game designer from Kursk.

Yoffe left with her mother in early March 2022 and never returned to Russia. Unlike many expats in Georgia, she does not spend her time making catastrophic predictions and looking for mistakes in Russian history, but rather she immerses herself in the Georgian historical context from the ancient times to the present. Her solo exhibition ‘War Crimes’, opened in September 2022 at the Baia Gallery and focused on the tragedy of the war in Abkhazia. She literally had to immerse herself in the events of 1993 before creating a series of works called ‘Bodies’. “Rhythmically arranged black lines in the paintings organize the composition of the standing and lying figures, while spots mark the heads. The composition of the central painting is constructed in such a way that at a distance a multitude of lines and a spot of a head in the centre form an image of a crucifixion”, Yoffe explains. The exhibition was a great success, but the artist revealed anxieties that she might be criticized by the Georgian art community because of her Russian citizenship.

Her virtual art project Xanax Tbilisi, to be unveiled in March, was born because of the constraints of real space. It is the world of Tbilisi through the eyes of expats, a space you can walk around which is constantly in a state of expansion. The content will eventually include Alisa Yoffe's virtual studio, spaces where you can donate to charity organizations, street where you can see the work of local young graffiti artists, and staged concerts.

Russian artists in residence at Ria Keburia Foundation

The Ria Keburia Artist Residency and Foundation is exceptionally active in Georgia’s artistic community, inviting international art professionals and welcoming Russian artists. Throughout the past year more than fifteen artists from Russia have stayed here, including Alisa Yoffe, Ustina Yakovleva (b. 1987), Polina Zaslavskaya (b. 1984), and Gosha Elaev (b. 1989).

Moscow artist Ustina Yakovleva came to Ria Keburia in May 2022 at a time when the horrors of the conflict were unfolding and it was hard for artists to find their own voice. The residency in the picturesque landscapes of Sakartvelo helped Yakovleva to gather her strength to move forward. “I ended up at the Ria Keburia Foundation residency in Kachreti thanks to artist Nastia Omelchenko, who invited me to join their group. There were seven of us in what was like a summer camp there was a warm family atmosphere. For me, it was like rehab, where I could relax, recover and even produce new work. I felt safe here.”, says Ustina Yakovleva.

The group exhibition ‘Contemplating Dogs’ which is on view until 5th of April has recently opened in the exhibition rooms at the Foundation. It summarises research by its residents into the possibilities of contemporary Cynicism (an ancient Greek philosophical teaching based on union with nature and the simplicity of life, as well as the importance of asserting one's lifestyle). Five young Russian artists who are taking part in it looked for possible links between the modern tradition of hospitality, so prominent in Georgia, and ancient Greek philosophy.

The group exhibition ‘Contemplating Dogs’ which is on view until 5th of April has recently opened in the exhibition rooms at the Foundation. It summarises research by its residents into the possibilities of contemporary Cynicism (an ancient Greek philosophical teaching based on union with nature and the simplicity of life, as well as the importance of asserting one's lifestyle). Five young Russian artists who are taking part in it looked for possible links between the modern tradition of hospitality, so prominent in Georgia, and ancient Greek philosophy.

Polina Zaslavskaya, artist, curator, coordinator of feminist and queer feminist initiatives, and a participant of the exhibition, noted among the pros of the residency that absolute freedom was given. As one of the residents, Gosha, said, 'We are like ripe grapes for which the necessary conditions have been created. And then... well, either we will succeed, or we won't. Creating a cultural policy at the time of an armed conflict is a very complicated and thankless task, and even more unnecessary now (this is purely my opinion). But to give an artist the opportunity to survive for a few months and think about what to do next, or what not to do, seems like a worthwhile thing to do.

Mayana Nasybullova and her Hospitable Garden gallery

Novosibirsk artist Mayana Nasybullova (b. 1989) came to Georgia six months ago. On 9th of March, she unveiled her second open-air exhibition project “At home and near home”. It took place in a small garden adjacent to her house in Tbilisi, which has become “a refuge for my creations that are forever migrating from place to place, a place not burdened with longing for the past and hopes for the future”, as Mayana Nasybullova puts it. The leitmotif was Dasha Goffman's work – graffiti on the wall with a Georgian proverb, an analogue to the Russian folk saying “At home even walls themselves help you”, posing the question “What to do if the walls do not help and there is no home anymore?”.

The wholesome spirit of the open-air gallery allows participants to feel safe and undergo the experience of re-assembly through a reflection on the year lived. This journey is inevitably individual: in the form of Nino Chechelashvili's urban 'hieroglyph' – a counter-relief made up of recognizable elements of Tbilisi's everyday street culture (skateboards, Soviet signs, wires and metal rods perpetually sticking out from everywhere). Or a performance, during which washed pictures of the city are hung on ropes like the laundry in ordinary Georgian courtyards.

Nasybullova invited all interested artists to participate. Members of the new Tbilisi-based self-organized group Ponichala, named after the district, also took part in the exhibition. These are free workshops located in an old warehouse building. At the moment there are fifteen independent artists practicing performance, sound, fashion, sculpture, video, photography, painting, tattooing and jewellery art.

Speaking about Russian expatriate artists, Nasybullova noted a change in the way they define themselves, the destruction of the imperial colonial base. “It seems to me that this concept of Russia and Russianness is now as if it is in a phase of deconstruction or even complete destruction. I think a lot of people will experience a powerful redefinition of themselves. I can already see some signs of this process. It will not be a union of Russian artists, but an appearance of artists from Siberia, from Ichkeria, from Tatarstan and the Urals.”

The cultural life of expats

There is no art gallery in Georgia yet that would exclusively support Russian émigré artists. Neither is there an established community of new collectors and art connoisseurs among the newcomers. However, many co-working spaces are being opened by expats, where various cultural events, including exhibitions, are planned – for example, the DUST project with its evocative name referring to the myth of creation of man from dust, and the possibility of rebirth.

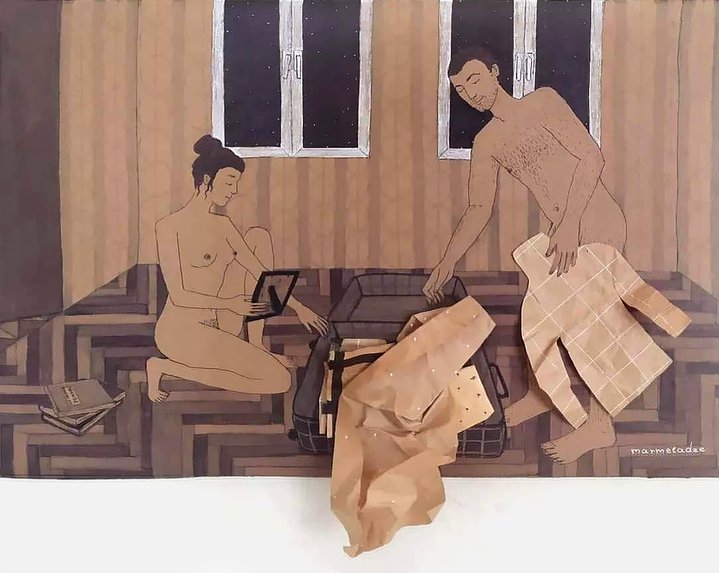

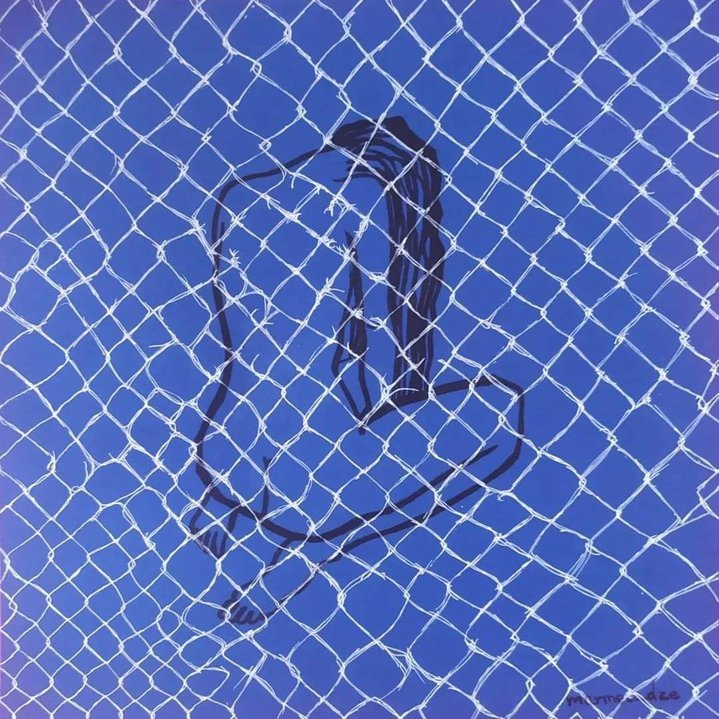

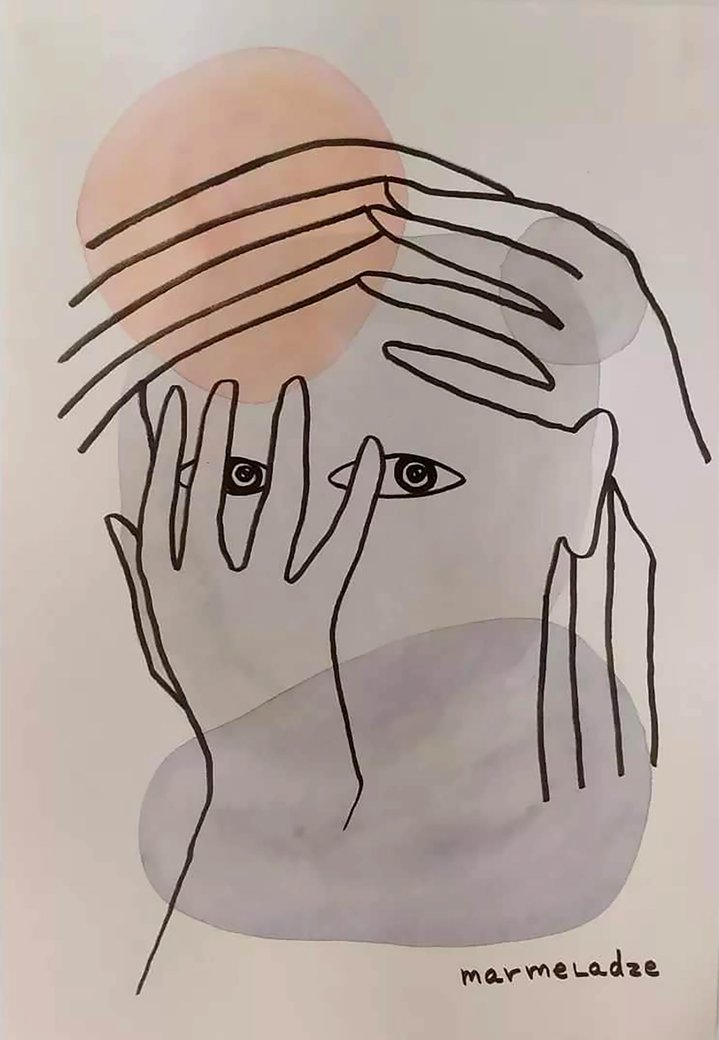

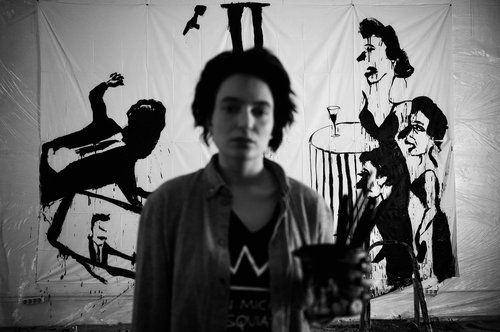

Another small space in Tbilisi where you can see the work of expatriate artists is the bookstore and lecture hall Auditoria, opened by the founders of the Russian project ARHE. Last November it hosted an exhibition of Russian graphic artist Mar Meladze, who also came to Georgia after the war started. To say that this space is perfect for exhibitions would be an exaggeration. Yet here one really can experience the creative vibe of émigrés, drink a glass of Georgian wine and read new books in Russian.