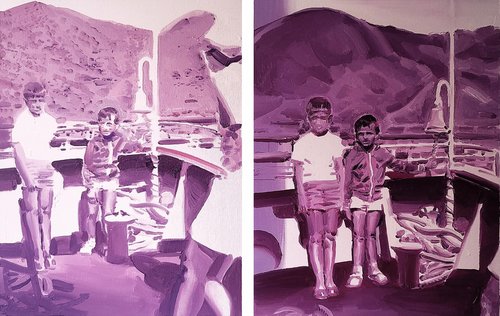

Katya Granova. Posing for a photograph, 2019. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of grart.net

Russian Artists in Transit in Flux in Exile

There has been a dramatic change in the Russian art scene over the past year with a mass exodus of artist movers and shakers leaving Moscow or St Petersburg, or other cities from all across the nation. Where are they now and what does the future hold for them?

The dire geopolitical events of the past year have created the biggest wave of emigration from Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union, and as many as up to one million have left the country since February 2022, and there is no sign of this stopping any time soon. The root cause may be one and the same, but individual reasons vary from the political to the emotional or just the practical. The first wave left right after 24th of February 2022 was mainly for personal, moral and political reasons. A second wave happened after partial mobilization was announced in September that year – men, and their families fearing army conscription. Those leaving the country are young, educated professionals, those working in IT, however, migration among cultural workers is also high, and especially artists.

Politically engaged artists have left because of repression or persecution for their artworks. Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina (b. 1988) escaped house arrest in a notorious stunt disguising herself as a food delivery courier. Photographer and activist Danila Tkachenko (b. 1989) also made the headlines for his attempted protest action planned to intervene in the state celebrations of Victory day on the 9th of May. Hidden distance-controlled smoke bombs were supposed to cover Red Square in blue and yellow smoke during Putin’s victory day speech but the action was intercepted by the authorities. Tkachenko had preliminarily left Russia to avoid repercussions, but once he was away he was shocked to discover that his friends and family were still subjected to repressions on his behalf. Tkachenko is now in Europe working on a large photography and performance project with the working title “inversion” bringing the plight of refugees to the attention of the EU and collecting donations to support Ukrainian Armed Forces.

A police search of their home and confiscation of property triggered the immediate departure of Dmitry Vilensky (b. 1964) and Olga ‘Tsaplya’ Egorova (b. 1968), founding members of the Chto Delat’ collective which has been active since 2003 in connecting the fields of art, activism and political theory.

Egorova explains: “Because in this nightmarish molasses where we try to breathe, live and find one another, you never know what will make this sticky substance bubble, suck and squelch. Any given word spoken by us can become food for this sprawling substance that turns everything inside out, making even simple things indistinguishable: left and right, life and death, everything is volatile and false. I’m sick of everything. We don't know who we are. Witnesses? Suspects? Today we might be witnesses, and tomorrow already suspects.”

Having made it to Germany receiving humanitarian residency (a status allowing victims of repressive politics to seek refuge), they later managed to extend this to twenty-five ex-students and other participants of their activities by including their names in their criminal case, offering an inverted lifeline by incriminating them in Russia.

For other artists the immigration process was less traumatic, many had a second citizenship (in many cases Israeli); artistic connections with institutions abroad, often travelling for residencies and projects; or had been previously living between two countries. Many confess they had already thought about emigrating, with the events of the past year becoming the straw that broke the camel’s back. A commune of such Russian artists exists in Hungary, among them Ivan Plusch (b. 1981) and Irina Drozd (b. 1983). But the latter does not consider her departure final, neither does it solve existential problems: “I am a Russian artist, it’s a fact, I will be Russian no matter where. […] It’s a tough time. Us Russians are still f***ed wherever we are. Here, and back in Russia, because we left.”

Yet often the choice of country seems random. Many took decisions quickly based on whatever flights were available or based on visa restrictions. Georgia became a top destination, according to estimates there are some 100,000 new Russian migrants living there. Among the many artists are Ivan Dubyaga (b. 1980), Dagnini (b. 1987), Alisa Yoffe (b. 1987) and Liza Morozova (b. 1973).

Through this experience, Yoffe is now re-connecting with her Georgian ancestry, her sharply critical laconic works which had always carried an activist message back in Russia are now shifting focus onto the Russian-Georgian relationship. Her new virtual world project ‘Xanax Tbilisi’ contains a Putin avatar kneeling in front of the Georgian parliament “two regions of which have been occupied by Russia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia’” says Yoffe “this is an homage to Maurizio Cattelan’s Him [a sculpture of Hitler as a little boy kneeling in prayer].”

One of Russia’s best known performance artists Liza Morozova has also found herself in the Georgian capital. With a PhD, participation in 150 international exhibitions and 17 biennales under her belt, her current worldview is depressing: “My plans are modest. Not to die of starvation, not to go insane, to adapt at least somewhat and accept this reality, but so far I can’t. For now, absolutely everything is difficult, unexpected and new.”

Visa-free destinations such as Armenia, Georgia, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey and Central Asian countries are often temporary stop overs for people waiting to get permits for further travel. Brothers Stepan (b. 1987) and Vasily (b. 1991) Subbotin, members of Krasnodar’s ZIP art group, stopped off in Yerevan on their way to Berlin and a third member Egenii Rimkevich (b. 1987) is still there. Since 2009 the artists were instrumental in generating Krasnodar’s grassroots art scene, founding various local festivals, an art centre and educational institute, with almost no external funding or help. These self-organisational skills are helpful in these difficult times. A flat in Yerevan has been made into an artists’ shelter, curated by Marianna Kruchinski of Krasnodar’s Typography Contemporary Art Centre (now closed down and pronounced to be a foreign agent in Russia).

Many artists have turned to activism, charity work and mutual support schemes in emigration. In London, painter Katya Granova (b. 1988) who has been part-based in the UK capital for some years since her studies at the RCA has set up a helpline for artists and other cultural professionals to apply for the UK’s Global Talent visa and 200 visas have been secured to date with her help. She sees it as rescuing Russian culture, her project called the ‘Philosophers Steamboat’ referring to the exodus of intelligentsia from the Soviet Union by ship from Petrograd a century ago.

Pavel Otdelnov (b. 1979) has relocated to the UK where he has had a solo show at Pushkin House. Yet even with a visa and some recognition, it is hard to relocate and re-build your career in a new country: “The difficulties are: living in a place where you know almost no one and no one knows you. After a well-established life in Moscow, you have to start again from scratch. There are financial difficulties, there is anxiety about the future, typical I think.” A sentiment, which to lesser or greater extent seems universal.

For some these difficulties eventually amount to tipping the scales to push them back to Russia. Alexander Povzner (b. 1976), happened to be in Germany for an exhibition when the mobilization was announced in September, and he didn’t intentionally flee, his current exhibition Berlimbo (Gotisches Haus Spandau, until 5th March) shows groups of hanging, wilting, anonymous paper figures, evocative of his own state of mind. Now he is considering a return: “Perhaps I will go back to Moscow, because all my closest friends are there, common language and the possibility to survive through work. Although it was unbearable to live and work there over the last year, I have no idea how to survive here. For me, all this is a strange, very difficult but incredibly interesting period.”

In many cases artists prefer to stay in a constant state of transit. Sergey Bratkov (b. 1960) spent several months in Frankfurt, followed by Paris, then Berlin, Frankfurt again; Belgrade and Montenegro, during which he has had three solo and five group exhibitions. Konstantin Benkovich (b. 1981), Victoria Lomasko (b. 1978) and Marina Koldobskaya (b. 1961) are others who have travelled and exhibited extensively in this period, presenting a very public face and renouncing the alleged tendency to cancel Russian culture.

The type, genre and medium of art being produced over this past year must also be considered as well as its intended audience and any cultural and linguistic component. Two artists who found themselves in Montenegro have diametrically opposing approaches. Slava PTRK (b. 1990) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) is a renowned street artist, he finds ruined buildings in Montenegro, making laconic additions in black paint which imbue these environments with new, poignant meaning “it’s about my internal feelings and emotions in response to what’s happening, but quite abstract.” Ivan Tuzov on the other hand, creates predominantly digital pixel artworks to be disseminated to the public back in Russia as memes.

“Artists are among those few who can express their experiences publicly, in many cases speaking on behalf of people who feel the same way but cannot be heard. I think artists and curators are responsible for what happens to the refugee identity” writes curator and critic Alexander A. Burganov who is researching the field. He has coined the term post-Russian artists to describe the phenomenon and has created a dedicated Instagram account [https://www.instagram.com/post_russian_artists/ ]

Nonetheless, many are choosing to keep a low profile. Many won’t talk unless in anonymity and did not want to be mentioned in this article for a number of reasons, mainly out of fear and mistrust as well as the fact they are struggling emotionally, psychologically or creatively. These silent ranks are also sizeable if invisible.

It is an incredibly interesting phenomenon, pertinent, difficult to study and quantify. The processes are still in flux, information is haphazard, the artists are under stress, and any information can also be used as a weapon or a threat. But time will come when we look back on this period in the history of Russian (or post-Russian as Burganov would have it) art, detangle and evaluate it, but for now we are in the thick of it, and much is still to come.