Russian artist Danila Tkachenko has recently shown a project he photographed in Syria

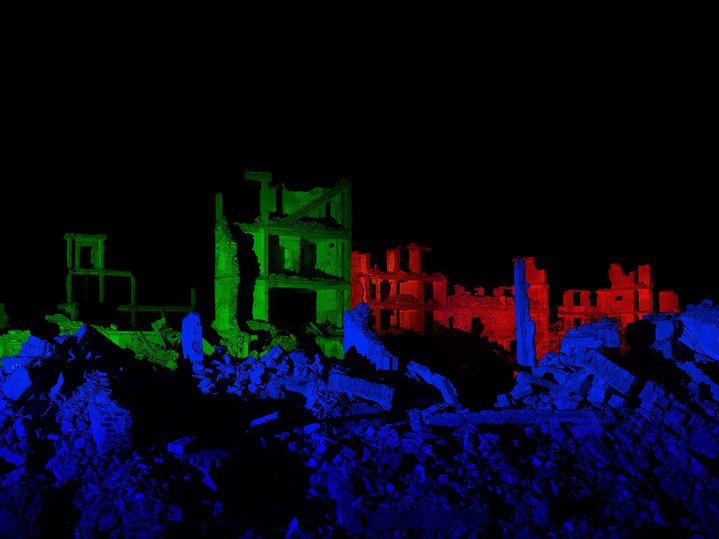

Danila Tkachenko. Bomb Shelter, 2022. Photography

An exhibition called Bomb Shelter was put up for just one day in the basement of a residential building opposite the Kremlin. It included striking images of disfigured victims of the conflict against a background of brightly lit ruins, and a live stream from Maidan Square in Kyiv.

In the dusty, scarcely lit basement of a large residential building, old-fashioned television sets glowed ominously in the semi-darkness. They showed unsettling images of ruins bathed in rays of unnaturally bright, multicoloured light, as if a concert or a dance show was about to take place. But no entertainers came to bask in the limelight. Instead, the heroes were survivors of the Syrian war who had lost their limbs in the conflict. Young men, dressed in nothing but loincloths, stare calmly into the camera. The images look both surreal and eerily topical. The exhibition opened just four days after Russian troops entered Ukraine. It was unveiled in total secrecy: no signs on the door, no ‘event’ page on Facebook. Invitations were sent by direct messages to a selected few. Organized by the artist-run Artpogost gallery and curated by Alexander Evangeli, a well-known curator and professor at the Rodchenko School, the show had the air of a carefully prepared impromptu event. Tkachenko’s projects, enormous in scale, complicated in production and thought-out to the most minute details, never leave much space for spontaniety.

Danila Tkachenko (b. 1989) won the prestigious World Press Photo award in 2014 for his series Escape where he captured on film present-day hermits. These were people who had left society for various personal reasons and led a harsh and solitary life in the woods. Often Tkachenko physically transforms reality before photographing it. He built temporary structures in front of half-ruined Russian churches to change the look of their crumbling facades, turning them into abstract compositions with a Suprematist twist. He set an abandoned Russian village on fire and photographed the roaring flames for his most famous (and controversial) project Motherland. Back in 2014 he traveled to Syria carrying coloured filters and projectors in his luggage. In the impenetrable blackness of African nights, he lit up ruined buildings with rays of brightly coloured light. He invited local men who had been disabled during the war to pose in front of ruined buildings for a fee. “I tried to hire some women, too, but they refused to pose naked”, he explained. The project was called ‘Theatre Sets’. Tkachenko showed it in the Athens National Museum for Contemporary Art and had put it aside for a while.

“When I was first asked to mount an exhibition in this basement, I refused,” the artist told Russian Art Focus. “Yet, after the events in Ukraine began, I was shocked, as well as everybody else, and felt the need to react somehow. It’s impossible to sit and do nothing in such moments as these. This project seemed like a perfect analogy, since most of the damage in that part of Syria was caused by Russian bombs”. Streamed live from a publicly accessible surveillance camera on Maidan, the central square in Kyiv, reminded visitors of the present, yet the streaming stopped abruptly during the course of the opening.

Tkachenko points out that his aim was to convey a sense of how unreal violence is, that there is some distance between it and us. “War is something that happens to someone else somewhere far away. We try to avoid any thoughts about it, in order not to become traumatized. There is a distance between our society and violence. Constantly flowing images transmitted by the media turn it into something illusory, some kind of a film, and we get used to it quickly.” Tkachenko used coloured light in order to make horrible reality look like a theatrical illusion: this was his way to show the blurred borders between the realms of real and unreal. “It used to happen quite far away, in Syria where a lot of people suffered and died. Now it is happening much closer to us. Could it happen here tomorrow?” he wondered, as did many Russians at the same time. “The location worked very well in the end of the day,” he observed. “Who are in the bomb shelters now? Us or them?”

P.S. The exhibition was initially supposed to last for three days, however, it was dismantled on the morning after the opening. “Some guys came in and asked the gallerist to take it down. I was not there and don’t know who they were”, says Tkachenko, who has recently left the country. “There are a lot of ‘siloviki’ (Russian term for employees of security, defense and law enforcement services) living in this building.”