Raise your heads

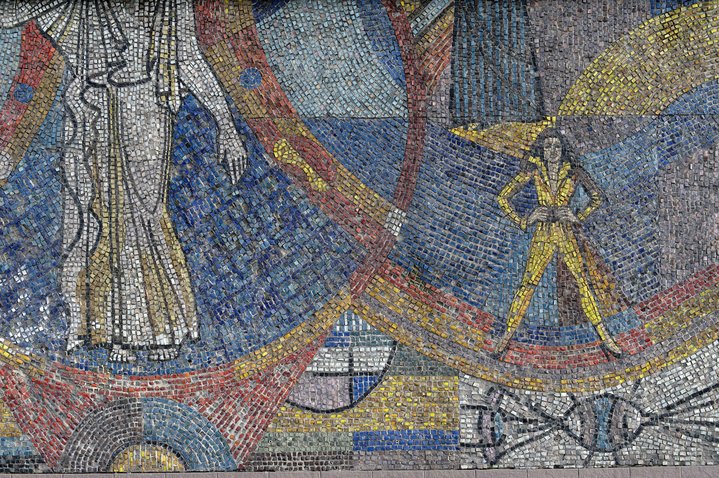

Yuri Korolyev. Cosmos, 1965–1969

What do we know on the brightest medium of Soviet monumental art

I came to live in the Soviet Union in October 1991, a few months before its official existence came to an end. Having never previously visited any of the communist countries in Eastern Europe, I was immediately struck, in a visual sense, by what I couldn’t see – the advertising – and how the streets were adorned instead with mosaics, bas-reliefs and muscular statues.

While Lenin and slogans such as “We are building Communism” were omnipresent, as I had expected, another surprise – since my childhood in England had been punctuated with dire warnings about the possible arrival of Warsaw Pact forces in London by tea-time – was that the most common phrase appeared to be: “Peace to the World.”

When I think back to the colours of that winter, they are overwhelmingly shaded grey, which is probably why the mosaics struck me as being so extraordinarily vivid. The first mosaics that I saw, and indeed amongst the very first that were made in the Soviet Union, were from a series of 35 oval panels decorating the ceiling of Moscow’s Mayakovskaya metro station. Opened in 1938, as the Stalinist purges were winding down, the mosaics depict “24 hours in the Land of the Soviets.” The artist, Alexander Deineka, imagined moments from the everyday lives of the citizens of this new country, barely twenty years old, a portrayal very far removed from the actual and far more torrid history of the 1930s in Russia. His figures are invariably athletic and drenched in both sunshine and innocence – as if shouting a last hurrah of the Russian Avant-Garde. “Raise your heads, citizens, and see the sky,” Deineka urged, “In mosaics, bright and illuminated.” Though for much of the brightness he was indebted to Vladimir Frolov, one of the Tsarist era’s most accomplished religious mosaic artists, who would die of hunger a few years later during the siege of Leningrad.

That upward gazing or heroic stance was to remain a constant for Soviet mosaics. A few years later, during the war, at the Novo-Kuznetskaya metro station, Deineka would create another set portraying Soviet workers as the war raged all around. Amongst the designs is a scene from a tractor factory in which male and female workers are dressed in blue dungarees, the women not dissimilar in style to America’s “Riveting Rita” and this reverence of the worker was to remain a steadfast motif for Soviet mosaics.

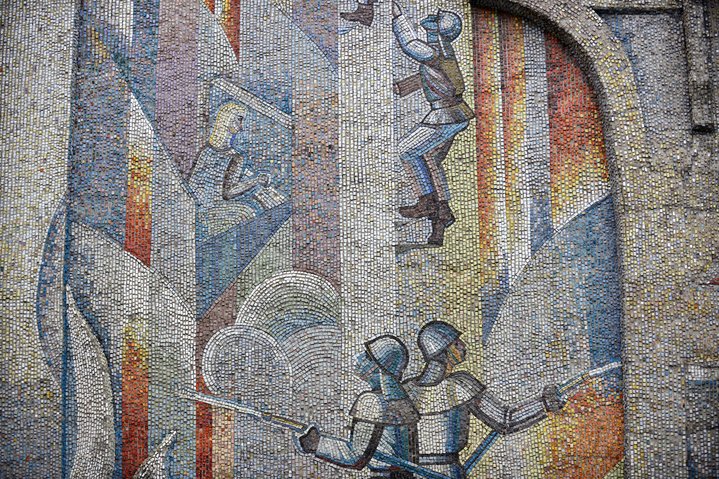

After the war, the creation of mosaics spread not just in Russia but across the republics of the Soviet Union, as a centralized system was used to approve designs and sketches. Mosaics were perceived largely as elements of propaganda rather than artistic creations of individual merit but most of all they were practical – easy to clean and resistant to weather conditions when placed outside. To facilitate their production new factories started fabricating mosaic pieces - previously the stones and pieces for the mosaics had been taken from Tsarist stocks in St. Petersburg – and so they also became much easier and less expensive to make. The mosaics themselves could be done in almost any size or complexity, chosen according to the building they were meant to decorate, whether it was showing firemen rescuing a blonde woman stranded in a tall building or technicians and workers standing next to looms at a textile factory.

There were, of course, universally revered figures, in particular cosmonauts, whose unparalleled deeds – both inspiration and proof of the prowess of the Soviet system – meant that their representation could be placed anywhere from institutes to bus stations. Indeed, from the 1960s cosmonauts were the most common figure in mosaics, their depiction either based on Yuri Gagarin, the first man to travel in space, or Alexei Leonov, the first man to walk in space. At the entrance to the Russian Meteorological Centre in Moscow, Leonov is shown parallel to the ground as if hanging to the edge of his spaceship as it spins around the earth.

But there were also other subtler messages transmitted in mosaics such at the equal role of women, a point that was indicated by making women the same height as men in the mosaics. In the new Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Gorky Park, Moscow, the Rem Koolhaas designed museum has been shaped around the shell of a Soviet building that housed a restaurant named “The Seasons of the Year” with a large mosaic depicting a long-legged, beautiful woman floating through the leafy park. There is a strange sense of liberation in this image, finished in 1968, a whiff, though probably not a very strong one, of the social upheaval shaking the world outside the USSR in the late 1960s. Even more strident is a mosaic from the late 1960s placed on the front of a women’s fashion store in the east of Moscow showing a woman in a yellow jump suit and high heels.

While there were many abstract mosaics – perhaps safer politically for the artists – most embodied Soviet ideology portraying figures who were considered examples of the right kind of Soviet citizen: hard working, team players, upright and intelligent without being overly intellectual, since these mosaics were placed mostly in places of work and social interaction. The images endeavored to symbolize messages that were easily decoded by those who saw them, just as in Tsarist times, as religious icons whose images and symbols were understandable to all.

Today, I have the impression that many Muscovites are either blind or impervious to these mosaics. Already, a large number have simply been removed as the buildings have been torn down or redeveloped. Sometimes advertisements or shops signs obscure them. When I went to the Russian State University of Physical Education I asked a student for directions to the large mosaic depicting an athletic relay team. He told me emphatically that there was no mosaic. I went around the corner of the next building and there it was; all 30 metres of it. I could only conclude that, for those born after the end of the Soviet Union, these mosaics are expressing a forgotten language.