Persistence in Flux: The Past and Present of Net Art

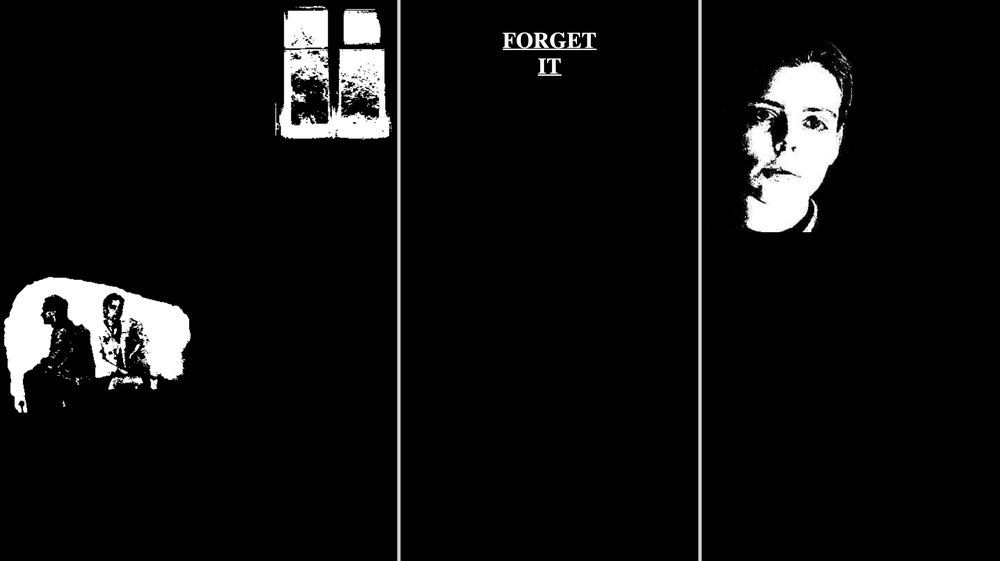

Olia Lialina. My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, 1996. Courtesy of the artist

From the earliest days of the internet artists started using this new and unfamiliar technology as a medium to comment on society as it changed around them. Surprisingly, many of them came from Russia, where access to the latest technologies in the 1990s was much more limited than in the West.

The proliferation of internet protocols and digital technologies in the early 1990s introduced new channels of communication with which to redirect discussions around societal mechanisms, identity, ownership, simulation, and other critical issues of the dial-up era. The intoxicating energy of the www-environment, where the most diverse of media from audio to gameplay could coexist, captivated early internet explorers. Artists quickly saw that local online events could bring access to global audiences while replicating methodologies once reserved for major institutions. Art created for, through, or by means influenced by the internet came to be known as net.art. The browser became its platform.

Net.art pioneer, Moscow-born Olia Lialina (b. 1971), went from being a journalist and film critic to a net-artist over a few weeks. Her seminal work, ´My Boyfriend Came Back from the War´ created in 1996, leverages cinematic montage through an interactive narrative interface, where isolated images, GIFs, and hypertext navigate viewers through the story of a couple reunited at the end of a war. As users progress, the screen gradually fractures, forming a mosaic of black squares and rectangles. It was a work that achieved iconic status, spawned numerous remixes around the world, prompting Lialina to establish the ´Last Real Net Art Museum´ in 1998, a digital reinterpretation of André Malraux’s (1901–1976) concept of the museum without walls (Le Musée Imaginaire, 1947). In her essay ´All You Need Is Link´, Lialina critiques physical net.art exhibitions as ‘the ugliest phenomenon of the contemporary art scene,’ as if asserting that net-artworks forfeit their radical autonomy when they are removed from direct web–user interaction and evaluated through the axiom of the Real.

Contextually, net.art draws a lineage with Dada practices in its aim to subvert the authority of conventional aesthetic standards. Alexei Shulgin (b. 1963), founder of the Moscow WWWArt Centre in 1995, exemplified this ethos in ´Form Art´ through the repurposing of interface elements—menu buttons and HTML boxes—as minimal compositional units that lay bare the structural syntax of the web. This work embodies an irony aligned with Guy Debord’s (1931–1994) notion of détournement, appropriating the Prix Ars Electronica application form while inviting audiences to submit their own works for the ´Form Art Competition´. Shulgin later articulated the movement in ´Introduction to Net.Art´, co-authored with Natalie Bookchin (b. 1962), as ‘a self-defining term created by a malfunctioning piece of software, originally used to describe an art and communications activity on the internet.’

The world wide web manifested as a nexus of emergent collective consciousness, populated by ethereal objects and events accessible through hyper-allusion—a system of indirect references to their physical existence. In ´Siberian Deal´, two artists, Austrian Eva Wohlgemuth (b.1955) and American Kathy Huffman (b.1943) travelled on the Trans-Siberian Express from Moscow to Irkutsk, conducting a performative exchange of Western commodities like sneakers and cassette players for local goods. They chronicled their progress in a proto-travel blog, fostering a real-time dialogic space that encouraged audience engagement via email.

´Siberian Deal´ was shown at Documenta X, which pioneered the integration of its own website as a conceptual component of the exhibition. Among the participants was the Jodi collective— Belgian Dirk Paesmans (b.1965), a former student of Nam June Paik (1932-2006) at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, and Dutch Joan Heemskerk (b.1968)—who emerged as radical reductionists of the online medium. Their lifelong project, ´wwwwwwwww.jodi.org´, exposes the internet behind the web, dismantling it into elemental components and reconfiguring them into a hyper-textual architecture devoid of practical utility. In ´Visitors Guide to London´, another dX project, leading British net-artist Heath Bunting (b.1966) presented a ‘psycho-geographical tour of London, ideal for foreign non-visitors, [which] comes with over 250 sites of anti-historical value.’

The 1999 Webby Awards which offered a $50,000 fund for internet achievements and collaborated with SFMOMA, signaled institutional recognition of net.art. At the ceremony, where Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page arrived on roller skates, controversy erupted when Jodi’s representative, upon winning over SFMOMA’s nominee Bill Viola (1951–2024) in the Art category, climbed onto the stage only to excoriate the establishment as “ugly corporate sons-of-bitches” before throwing the award into the audience.

By this time, Shulgin had proclaimed the death of net.art, while Lialina, appointed professor at Merz Academy in Stuttgart at age 27, had begun investigating ways to preserve the browsing experience of web-based artworks. The absence of centralized archiving meant that preserving the network´s heritage was crucial: web pages disappeared, and entire digital colonies risked extinction, as happened with the termination of GeoCities in 2008. Although temporality and extreme volatility are predominant qualities of net-artworks, major global institutions, including Tate and Whitney, initiated digital archives throughout the early 2000s. At the same time, credit for the preservation of net.art can be attributed to non-profit initiatives such as rhizome.org, ADA (Archive of Digital Art), and ljudmila.org.

In our fully networked society of 2025, when the singular notion of ‘technology’ no longer mediates between culturalactors, and instead of one ‘technology’ there exist multiple technologies that can make human life better or worse, the scope of issues first tackled by net.art pioneers has expanded. Zeitgeisty questions concerning the role of the subject in network society, copying and appropriation, virtual property rights, and online equality now animate a third generation of artists working within and on the network.

Among such practitioners is a Russian émigré artist living in Paris called Dasha Ilina (b. 1996) who employs varied usages of the computer environment across her practice. Her ´Centre of Technological Pain´ examines web-consciousness through a series of performances, installations, websites, DIY devices, and open-source solutions, and functions as a spoof organization aimed at addressing gadget-induced health issues. This project, received an Honorary Mention at Austria´s Ars Electronica festival in Linz, and later evolved into ´Be? Here? Now?´, a web resource designed in the style of the late 90s. Drawing its title from yogi Ram Dass’s spiritual text, ´Be? Here? Now?´it curates a collection of materials and techniques for achieving a ‘total technological detox,’ complete with viral videos, publications, and coaching sessions.

At SPAMM (SuPer Art Modern Museum), a file-oriented internet exhibition space, Ilina’s video performance ´Are You Watching?´ is showcased alongside works by digital visionaries like Canadian Jon Rafman (b. 1981) and American Jonathan Monaghan (b.1986), as well as an animation by Nikita Diakur (b.1982), a Moscow-born artist who has been living in Germany since 1992. His signature style leverages dynamic computer simulation to interrogate the boundaries between randomness and algorithmic precision, exposing the hidden infrastructures of digital environments. By subverting software tools and exaggerating processes developers seek to conceal, Diakur transmutes the physical world into an arena of visualization where logical frameworks catalyze inevitable accidents and destructions. His project ´Ugly´, which synthesizes influences from digital folklore, YouTube culture, tutorials, fail compilations, and—unmistakably—Russia’s slum landscape, has toured festivals worldwide. The project’s accompanying website, with its ‘Spiritual Wisdom’ menu tab and idiosyncratic typography, functions as an autonomous artwork, its animated background evoking—accidentally or intentionally—Lialina’s art.teleportacia.org.

Moscow-born Maya Golyshkina (b.2002), exemplifying new social net art, uses Instagram as both an exhibition space and a platform for critical discourse. Like Ilina, she adopts DIY methodology, crafting costumes and props from CDs, eggshells, cardboard, cigarettes, playing cards, and other found materials. Her self-portraits, primarily shot in her room in London, have generated attention from both network users and fashion industry arbiters. Already by the age of 23, Golyshkina had collaborated with Marc Jacobs, Balenciaga and Maison Margiela. In her anatomically nuanced performances, Golyshkina corrupts Instagram clichés, strategically disrupting the platform's aesthetic of sleekness—the norm of social networks. Through her manipulation of app-native strategies, she has actualized many net-artists’ aspirations for unmediated mass engagement.

Throughout three decades, net.art has never neatly fitted into contemporary art’s master narratives or ‘technology’ proper. Yet it persists as a quintessential medium for epochal representation, wielding tools and techniques of the computer environment that define contemporary existence. Within the contradictions and diversity of www-culture, where every individual is somewhat Marshall McLuhan, 'the most conscious media-specific activity that a person can create online’ (updating Lialina's thesis from her KIKK Festival 2022 lecture) remains the generation of their own virtual trace.