On race and racism

A new book called ‘The Wayland Rudd Collection’, a brainchild of Russian-American artist Yevgeniy Fiks, explores the representation of black people in Soviet propaganda and popular culture.

Few countries are good at tackling difficult memories. Histories of war, genocide and social and racial violence are more often minimized than taught, let alone made the topic of political conversation or memorialized in a public space. This is one reason why projects like ‘The Wayland Rudd Collection’ are essential: as a medium that gathers personal recollections and reckons with collective failure, but also one that produces space for critical reflection and change.

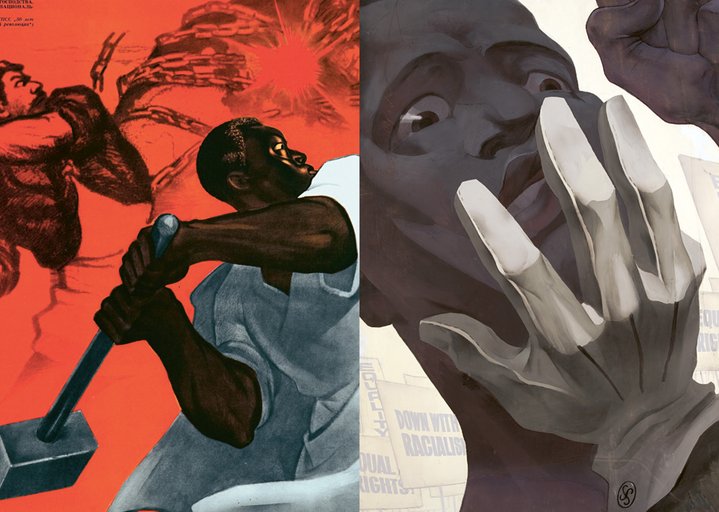

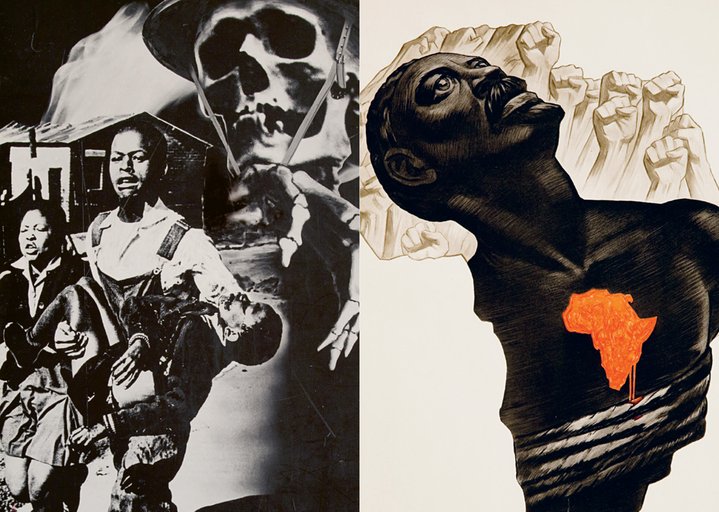

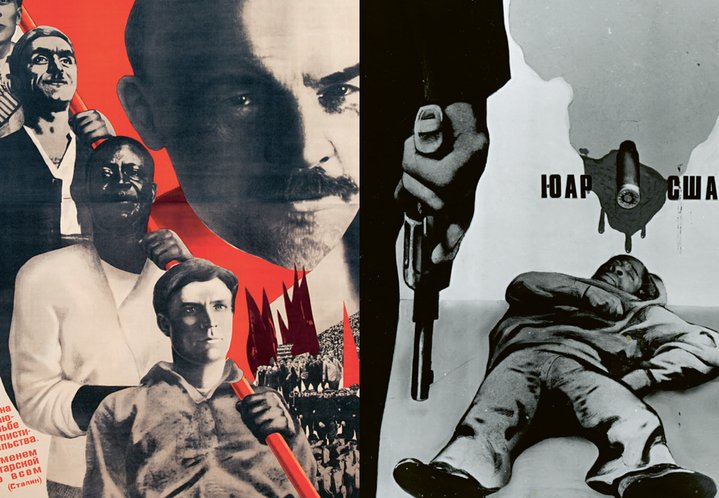

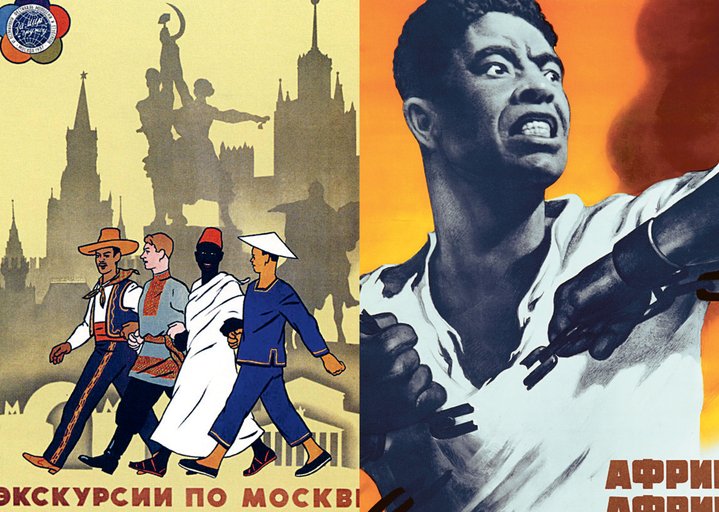

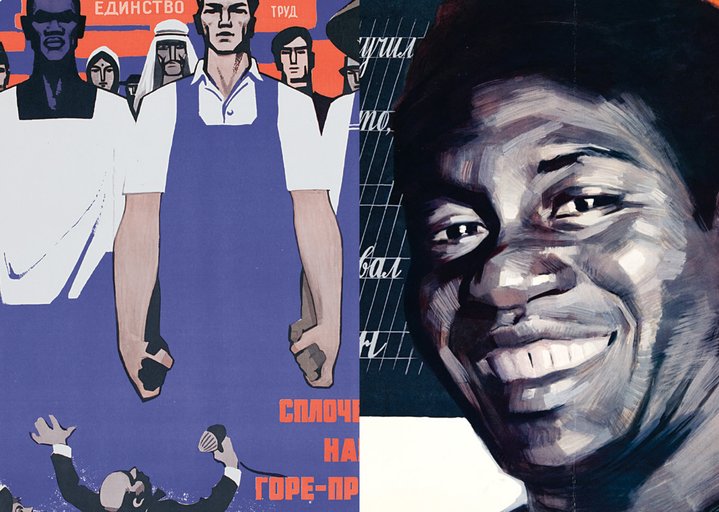

Initiated in 2014 by Moscow-born, New York-based artist Yevgeniy Fiks (b. 1972), the project began as a collection of representations (paintings, movie stills, posters, and graphics) of Africans and African Americans in Soviet visual culture. Fiks then enlisted contemporary artists and scholars to intervene in the collection, creating works that responded to the images from American, post-Soviet, and post-colonial viewpoints. Now, the collection has been collated into a publication. It features stunning colour reproductions of the images, interviews and several new essays that tackle racial politics and representation.

The collection’s namesake, Wayland Rudd, was an African American actor, who expatriated to the USSR in the 1930s. Fiks named the collection in his honour, noting that Rudd, who “defin[ed] in many respects the image of the ‘Negro’ for generations of Soviet people”, also lived a life that epitomizes “the complex intersection of twentieth century American and Soviet narratives”. (pp. 5) While Rudd often posed for propaganda posters and drawings and acted in films and theatrical performances before his death in Moscow in 1952, it is not only his image that fills the collection. Instead, it offers a panorama of Soviet visual history, spanning the Russian avant-garde’s montaged posters, to Stalinist Socialist Realism, through explorations of abstraction and the Soviet anti-colonial agenda in the postwar period.

The book includes essays by leading commentators of Soviet art and the Soviet experience. Art historian Christina Kiaer demonstrates that an aesthetic of anti-racism among Soviet artists and institutions emerged in the early 1930s, contemporaneous with broader attempts to align visual culture with ideology. Theorist Vladimir Paperny writes about Pauline Marksity, Rudd’s Jewish-American wife, and the couple’s struggles to find acceptance in Russia. But it is philosopher Lewis R. Gordan’s text ‘Dialectics of Seeing’ that you will want to read over and over again. Reminding his audience that America is also “postcolony”, Gordan underscores that race has and continues to intersect with class; that no political system will offer freedom to Black people as long as there is white domination.

The media in the publication illuminate the contradictory aspects of Communist internationalism. A stark graphic of the Statue of Liberty with a noose and a black man dangling from its torch presents a brutal reality: that American freedom has served a white future at the expense of coloured death. Other images, like Viktor Koretsky’s (1909–1998) poster in homage to Patrice Lumumba (1925–1961), a Congolese politician and pathbreaking independence leader in post-colonial Congo, convey unconditional dignity: eyes turned upwards, shoulders bound, and a heart that bleeds brilliant red. Such images stand in contrast to the numerous multiracial posters included in the volume, which almost invariably privilege a white Slavic or Caucasian man as the leader or instructor of other Soviet nationalities.

‘The Wayland Rudd Collection’ provides an essential resource to scholars of race and decolonialism, particularly those interested in the minority experience in an ideological context other than American capitalism. The media images collected in the book are powerful criticisms of American racism, European colonialism/imperialism, and South African apartheid. At the same time, they confirm that a Soviet “friendship of nations” could never be realized within the systemic hierarchies of ethnicity and race upon which it too was based.

Nevertheless, the images also revive a Marxist dialectical view of human relationships — one in which Lewis Gordan finds potential. “Non-dialectical thinking,” he writes, “leaves ideas and people trapped in the binary logic of contraries produced by universal positives and their absence, universal negatives… But the human world is dialectical and interactive. This is evident in touch, speech, love, and culture. Combined, these sensory and social actions build human worlds that enable us to transcend our physical space… To be denied these pushes us into ourselves and away from the human world. That inward movement is a form of withering to a point of implosion… Where air is lacking, we must go elsewhere to breath.” (pp. 10)