New layers of self-portrait genre

The self-portrait genre has been favoured by artists since time immemorial, yet the heavyweights of Moscow Conceptualism and Sots-Art managed to weave new and surprising layers of meaning into this age-old manifesto of the artistic ego.

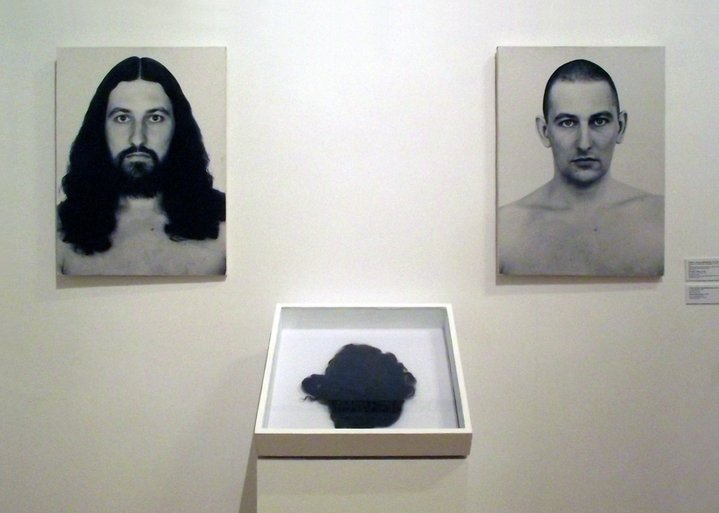

Alexander Yulikov

The Moscow artist Alexander Yulikov (b. 1943) is mostly known for his abstract paintings, which often spread into several canvasses. In his works, he re-thinks the heritage of the Russian Avant-Garde and challenges our perception of shape and balance, as well as painting as a medium. Some of his works are three-dimentional objects consisting of several layers of canvas glued together. The only performance in his career, called ‘Hair-cutting’, dates back to 1976. Within an hour, he bid farewell to his long curly mane, beard and moustache which made him look like a hippie version of Jesus. According to the artist, the resulting black-and-white “before” and “after” photographs, printed life-size, demonstrate the “transforming power of art in literal sense”. To emphasize the somewhat unsettling effect of his mesmerizing gaze, the artist had drawn identical pentagrams on both his images. The hair itself was saved for the sake of documentation and is often displayed at exhibitions, along with the photographs.

Viktor Pivovarov

The rich and surprising visual world of Pivovarov, an important artist of Moscow Conceptualism, stems from many different traditions and styles, among them the Russian Avant-Garde and Soviet children’s book illustrations. However in his ‘Self-portrait as a young man’, Pivovarov (b.1937) pays an unexpected and somewhat tongue-in-cheek homage to Albrecht Durer and Lucas Cranach the Elder. It belongs to the series ‘Lost Keys’ (2015), which was inspired by the works of Northern Renaissance artists. These eight paintings were first exhibited at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art, which holds Moscow’s biggest hoard of the European art of different epochs. The artist plays with the poetic and mysterious symbolism of Old Master paintings, which makes their hidden meaning obscure for us. Pivovarov, who is approaching the age of 80, ponders over his life in art, staging his youthful figure as St. Hieronimus. The artist is surrounded by this saint’s faithful companions, a lion, a hare and other wild animals and birds, transferred from the ancient hermit’s cave to Pivovarov's studio by force of his own imagination.

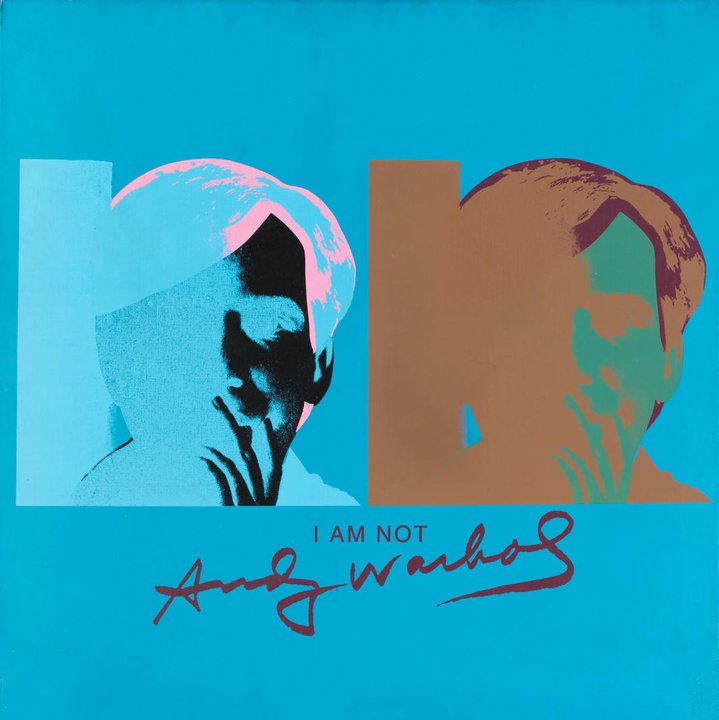

Yuri Albert

A younger protagonist of Moscow Conceptualism, Yuri Albert is known for his irony and sarcastic wit. His playful series of homages to the big names of contemporary art titled ‘I am not…’ is one of his best-known projects. In it, the medium and the message clash in an absurd and humorous way. Albert faithfully imitates the style of Roy Lichtenstein or Andy Warhol and at the same time proclaims that he is NOT either of them. He thus manifests his own creative identity in opposition to them. This seemingly jocular post-modernist game raises very serious issues of appropriation, artistic individuality and reproducibility of art. The selection of artists he chooses to contradict is certainly not random. Albert picks the ones who are widely known for some easily recognizable stylistic trait, but are at the same time important for his own artistic development, such as his mentor Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) or his peer Vadim Zakharov (b. 1951).

Komar & Melamid

The founding fathers of the Sots-Art movement, Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945) conquered the global art scene by mocking Socialist Realism and its hollow propaganda, dated visual language and blatant hypocrisy. In their famous ‘Double self-portrait as pioneers’ (1982), the duo poses as members of the Soviet youth organization whose rituals and uniforms were largely copied from the Boy/Girl Scouts' movement. Membership in the organization was obligatory for all the schoolchildren in the USSR. Mass-produced sculptures of a young pioneer blowing his horn at summer camps and parks, were a staple of the country’s landscape for many decades. The cult of Stalin had long been crushed by his successor Nikita Khrushchev and these two artists are ridiculing the shattered, but still ominous idol. The bearded youth blows his horn into the ear of the late tyrant’s bust, as if heralding the approach of Perestroika.

Boris Orlov

Moscow artist Boris Orlov (b. 1941) has been exploring the idea and mysterious allure of Empire for several decades. His primary medium is sculpture, yet in his whimsical ‘Self-portrait in Empire style’ (1995–1996) he chose to experiment with photo-collage. The result is a mosaic of seemingly incompatible cultural references. In the first panel, the artist represents himself in the style of an 18th century portrait, dressed in a fancy uniform hung with military decorations. However, in the following parts the illusion of pathos and grandeur is shattered. The subject shakes off his clothes and reveals a body tattooed all over with the same military decorations. This is a clear allusion to prison tattooes and, generally, to the criminal sub-culture which surfaced and blossomed in Russia during the what is now called the wild 1990s. At the same time, it is a subtle reminder that ideological clichés and the cult of power are not so easy to shake off.