New Jersey, USSR

Sergei Sherstiuk. The Cosmonaut’s Dream, 1986. Oil on canvas Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers. Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. Photo Peter Jacobs, 2014.

Norton Dodge, the American collector of underground Eastern European art, and the journey that led to world’s largest collection of Soviet Counterculture landing in New Jersey.

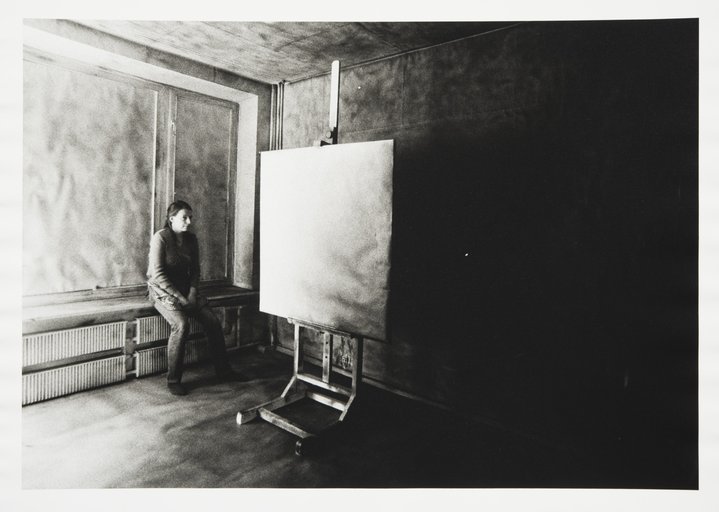

A generous slice of Russian culture from the last century can be found in an inconspicuous university town about an hour from Manhattan. New Brunswick, New Jersey, is home to the world’s largest collection of nonconformist Soviet art.

Its unwieldy name might have come straight from a Soviet archive: ‘The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University’.

Julia Tulovsky, associate curator at the Zimmerli, has a pithier way of describing the collection: “It’s a klondike,” she says. But of some 20,000 works by more than 1,000 artists, spanning from the 1950s to the early 1990s, “we unfortunately can exhibit only a few hundred pieces at a time,” she adds.

The Zimmerli acquired the vast majority of its Soviet collection through donations made by Norton and Nancy Dodge in 1991 and 2017. Fuelled by Norton’s nine trips to the Soviet Union from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, the Dodges amassed a huge amount of works revealing the diversity and intensity of art created not only in Soviet Russia, but also in Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus.

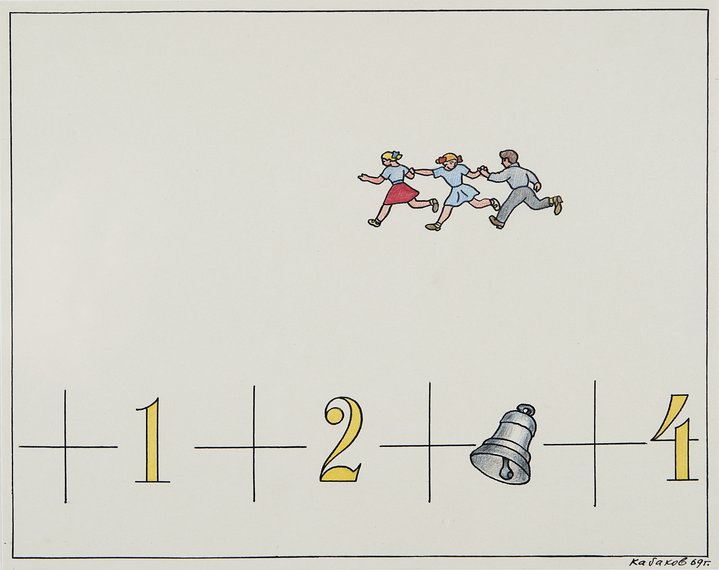

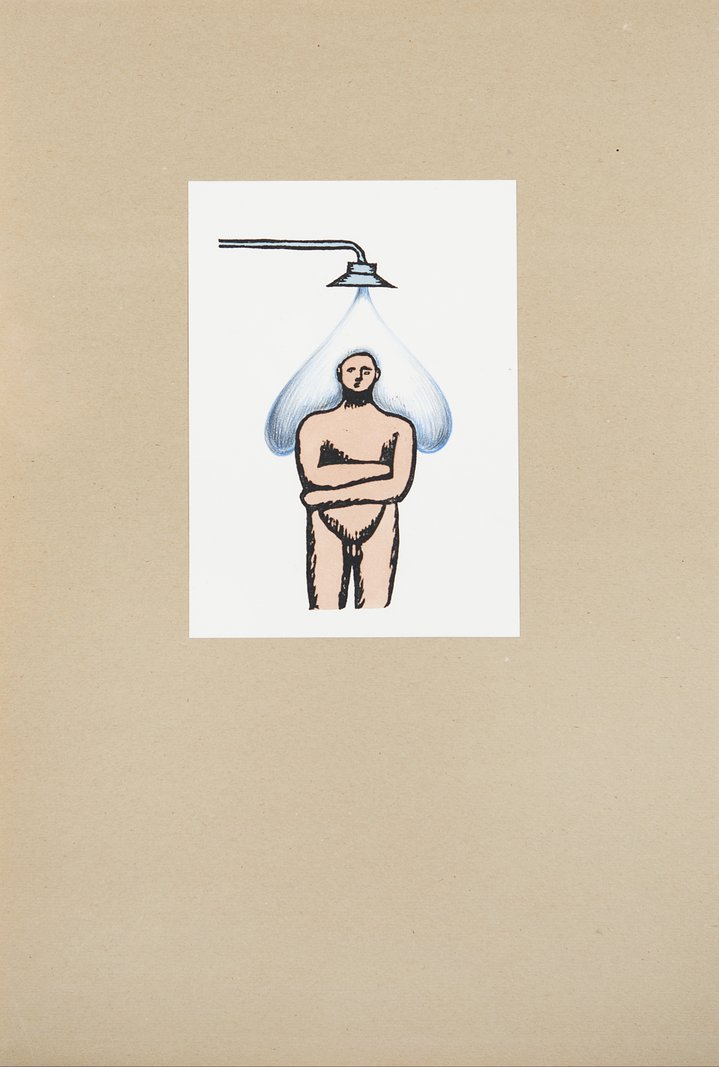

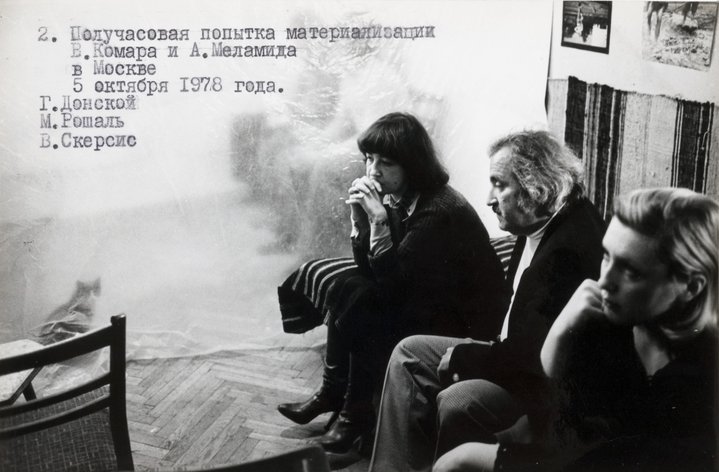

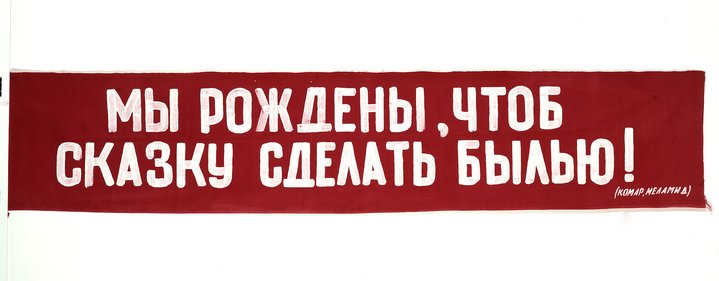

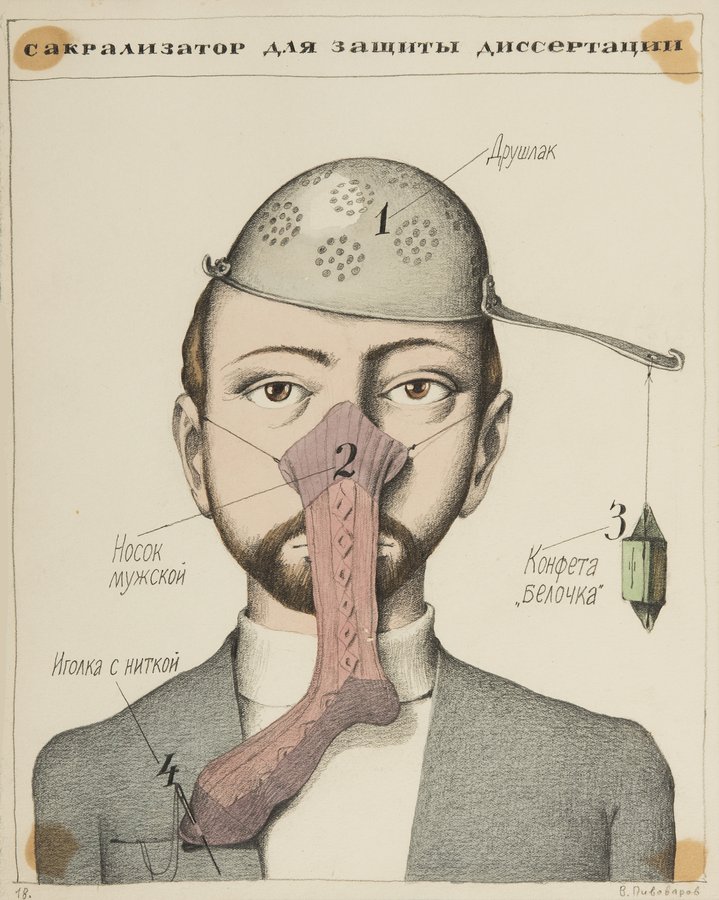

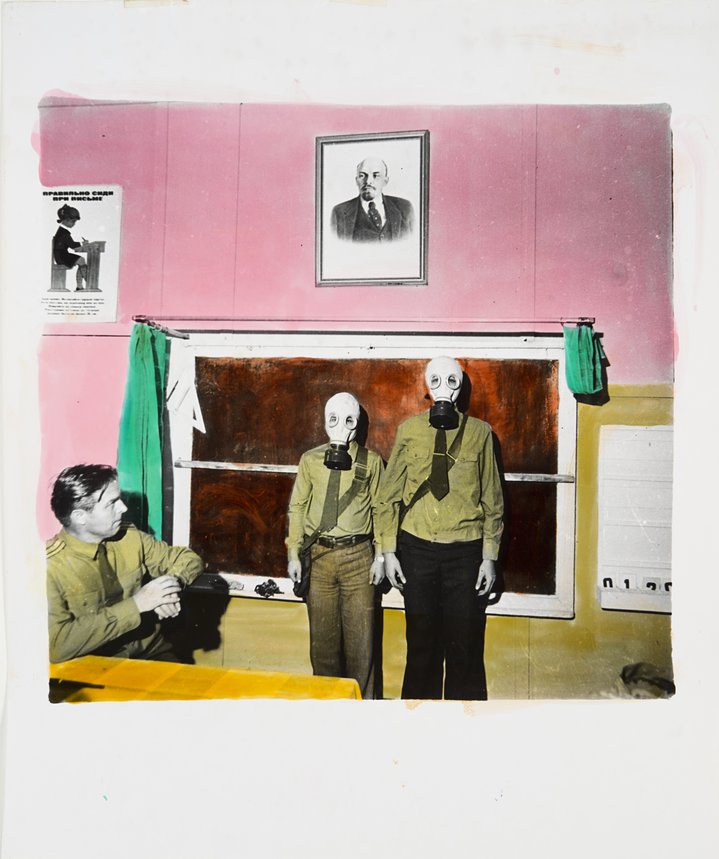

The collection boasts an almost embarrassingly rich swath of touchstone pieces by Moscow Conceptualists Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) and Viktor Pivovarov (b. 1937), as well as Sots-Artists Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), Vitaly Komar (b. 1943), and Aleksandr Melamid (b. 1945). One will also stumble upon the occasional icons of Socialist Realism, such as a copy of Isaak Brodsky’s (1883–1939) painting ‘Lenin at Smolny’, the aristocratic girls’ school the Bolsheviks turned into their headquarters during the 1917 Revolution in St. Petersburg.

The museum also contains a robust collection of post-Perestroika works donated by Claude and Nina Gruen, and of religious icons and 19th century Russian arts and crafts, donated in 1990 by George Riabov, who encouraged the Dodges to bring their collection to Rutgers.

Born in Oklahoma in 1927, Norton Dodge worked as a professor of economics at the University of Maryland. His father, physicist Homer Dodge, made a modest fortune through investment with the young Warren Buffet. In photographs, Dodge is easy to spot. His rumpled jackets and impressive walrus mustache do not fit the standard portrait of a risky and radical art collector. Still, by most accounts, that was what he was. According to a Russian artist quoted by James McPhee, who wrote a novel about Dodge, “His appearance may have saved him. He didn’t look American. He was sloppy. He was more like a Russian. If he was Russian, he would have been normal.”

Although Dodge expressed interest in art as a youth, he later studied economics and the Russian language. He graduated from Harvard and its Russian Research Centre. He first traveled to the Soviet Union with his father in 1955, amassing materials for a 900-page dissertation on the Soviet tractor industry. U.S. News and World Report published his snapshots of street life from this trip as photo-essays in 1955 and 1956.

Crucial to Dodge’s interest in Soviet art were such connections as the great collector George Costakis (1913–1990), whose collection of Russian Avant-Garde is now one of the crown jewels of Moscow’s State Tretyakov Museum. Clandestine purchases and smuggling them out of the Soviet Union were made possible by Dodge’s network of foreign diplomats and the trust he built with local artists. Until his death in 2011, Dodge declined to go into details as to how his enormous collection of Soviet art managed to reach his farm in Maryland.

Ars longa, vita brevis—life is fleeting, art is eternal— is one way of explaining Dodge’s passion. There was undoubtedly a political aspect to promoting Soviet counterculture, but of all the feelings that might have motivated Dodge, passion and hunger for knowledge played a much greater role than money or prestige.