New Indigenous Voices: Contemporary Art from Buryatia

Typomania in Buryatia, 2021. Photo by Nima Khibkhenov

Artists from this remote region in the southeast of Russia are increasing the international visibility of their culture, exploring questions of identity, language, racism, memory, and human relation to the land and environment. Timur Zolotoev, a curator from Buryatia overviews the emerging art scene of his homeland.

Far from the maddening crowd, located in Eastern Siberia, the Republic of Buryatia is home to the Buryat people. It is not only part of Russia but the broader Mongolian-speaking world, and Buryatia has an exceptionally rich culture shaped by indigenous Shamanic beliefs, Tibetan Buddhist traditions, and Russian and Soviet influences. Among the many talented new voices coming from this region and working both at home and internationally are new media artist Aryuna Bulutova (b.1993), performance artist Natalia Papaeva (b.1989), and artists Mila Balzhieva (b.1991) and Amgalan Rinchine (b. 1987). And alongside such strong individual voices, there are also exciting new independent cultural initiatives, notably Kheb-Hub in the capital of Buryatia Ulan-Ude and its partner Bargujin Tokum in a small village on Lake Baikal.

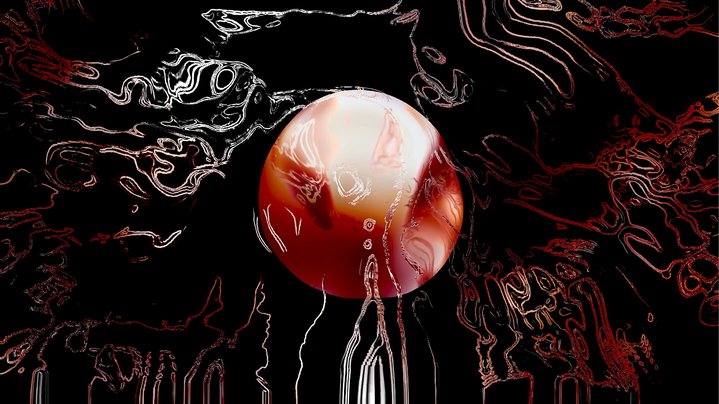

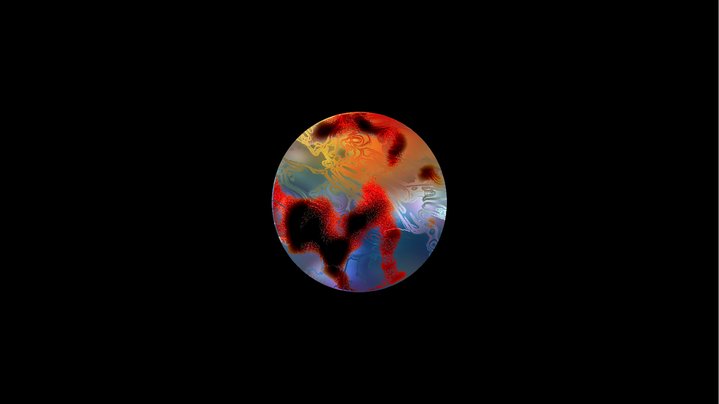

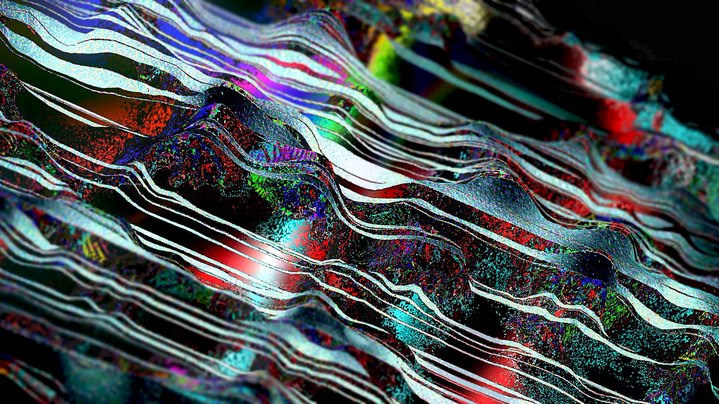

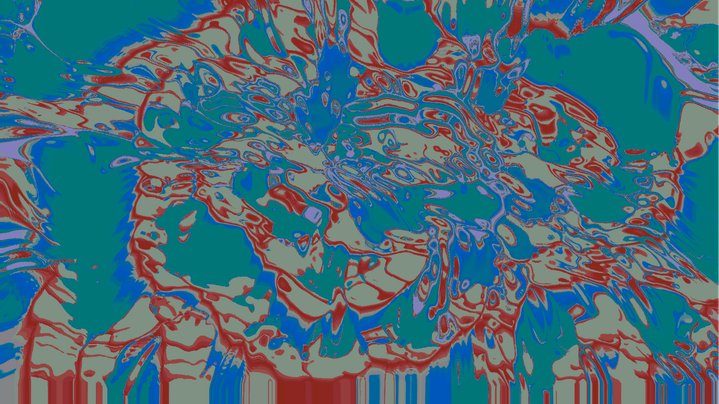

Artist Aryuna Bulutova explores the Buddhist and Shamanic legacy through the lens of digital and generative art. Her most recent video work called Dying was included in the group show The Endless Knot (which I co-curated with Dr. Christianna Bonin for the Lkham Gallery in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, and is on view until the 28th of February). It brings together Mongolian and Buryat artists to explore shared cultural imaginaries and spirituality. Bulutova’s interactive video artwork interprets the process of dying from the Buddhist perspective and walks the viewer through the eight stages of a fading mind. Colours and shapes morph and pulsate along with the meditative rhythms of Mongolian sound artist Davaajargal Tsaschikher and the presence of viewers within the installation.

Lake Baikal dominates the landscape in Buryatia and features in the work of many artists from this region. In her series Dream, Bulutova interprets dreams she had about this sacred lake and captures its serene and mystical magnificence. Ribbons flying over the water refer to the Shamanic tradition of tying pieces of fabric in sacred places to show respect to the spirits. The image of a circle, which often appears in Bulutova’s work, alludes to her grandmother’s embroidery hoops. Taking digital forms these hoops translate the craft that her grandmother passed on into a new medium connecting her with the family memories.

Natalia Papaeva. We are not from here, 2021. Video, cut from the performance. Courtesy of the artist

Born and raised in a mountainous region in the west of Buryatia, visual and performance artist Natalia Papaeva (b.1989) has been living and working in the Netherlands since 2013. Buryat oral tradition is central to her practice, helping her create poignant artworks that address such themes as loss and mourning, land and climate, language, racism, and identity. Drawing from her own memories and experiences, she creates performances, in which she combines singing, the spoken word, and storytelling. Many of her works can be understood from the decolonial perspective, but Papaeva says she takes a more intuitive approach to her practice, she aims not to over-theorize her performances.

In her 2018 performance Yokhor, she sings and then angrily shouts two lines from a famous folk song (the only two lines she remembers!) clutching at elusive words and expressing her frustration at the gradual loss of the Buryat language and culture. Grappling with the Russian word ponaehala, translated as ‘you are not from here’, Papaeva addresses the issue of racism in Russia. Analyzing, objectifying, and dissecting this word which is often said in public places to those who do not have a Slavic appearance, the artist neutralizes the effect of the word ponaehala extracting it from any social context or meaning. We have the power to give words their meaning but also to negate them.

Since the start of the armed conflict in the Ukraine, Papaeva has been writing poetry to express a sense of personal outrage. In a recent performance, Papaeva placed one of these poems in an envelope and gave it to artist Ceola Tunstall-Behrens to read it out loud, while she stood by in silence. The words were too painful for her to read them aloud with her own voice.

Born in Ulan-Ude in 1991, interdisciplinary artist Mila Balzhieva is now based in Vienna, where she is finishing her MA at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. Taking a holistic approach to her practice, Balzhieva combines conceptual and theoretical aspects of her work with a spiritual dimension. Informed by the indigenous Buryat perspective on nature, she researches the themes of multi-species communication and plant subjectivity.

In her video work In A Language We Don’t Understand made in 2020, Balzhieva roots consciousness deep in the woods, reminding the viewer that the forest itself is a living being full of mysteries where everything is interconnected. Reflecting on traditional Shamanic beliefs, she asks what would happen if you went into a forest with quiet respect seeking harmony with the creatures and nature living there. Would the forest share its hidden life and secret messages? In another work, inspired by a Basho haiku, Balzhieva collaborated with artist Sasha Shmeleva to create Blossoming Field, a series of textile and embroidery works that deepen perceptions of nature, writing, and womanhood. HYMYYN BICHIG Human Writing, is a typography artwork that explores the traditional vertical Mongolian script that the Buryats and other Mongol peoples used up until the beginning of the twentieth century. Addressing the endangered condition of the Buryat language, Balzhieva observes that with language you also lose very unique ways of understanding your land, and you can eventually lose connection with it.

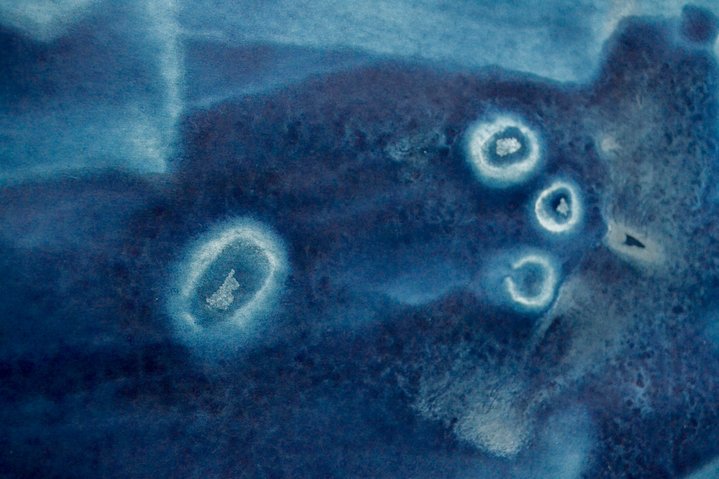

Amgalan Rinchine (b. 1987) is a multidisciplinary artist based today in Ulan-Ude. His practice is centered around researching Buryat identity. Working across diverse media, Rinchine explores the themes of family memory, Buryat mythology, and Shamanic cosmology. Born and raised in a Buryat-speaking community, he is particularly interested in the preservation of the Buryat language which is disappearing. In His Tongue is Broken, he placed 14 sheep tongues in jars filled with formaldehyde to symbolize the 14 dialects of the Buryat language; and recorded eight Buryats who already could not speak in their native tongue to read a contemporary novel in Buryat. The stumbling voices of people who wished they knew the language of their ancestors documents with poignancy the current state of the Buryat nation. The Sun of Buryatia is Rinchine’s manifestation of his love for his native land. He used cyanotype to record the solar light of Buryatia, claiming that this was the only way he could find the exact deep shade of blue which is evocative of the Eternal Blue Sky, the supreme force of the Shamanic pantheon. In another work, Dotor, Rinchine attempts to reach inside the Buryat culture. Sheep intestines are a crucial part of the traditional nomadic Buryat cooking tradition, where every part of an animal is used as sustainably as possible. Working with real animal gut, Rinchine made ceramic casts and bowls, looking for a kind of idiosyncratic beauty.

Alongside these strong new voices, there is a nascent artistic and creative infrastructure in Buryatia. In recent years, the capital city of Ulan-Ude has seen a grassroots creative boom, with independent cultural initiatives, such as Kheb-Hub creating spaces for self-expression and the cross-pollination of ideas. Located in the spacious building of a Soviet-era printing house, Kheb-Hub accommodates artists, architects, graphic designers, photographers, and calligraphers. A unique cultural space in the city, it plays host to exhibitions, festivals, concerts, lectures, and workshops, including international events such as the Typomania in Buryatia festival of graphic design and calligraphy, the Istvan Orosz exhibition as part of the Days of Hungary in Buryatia, and the Mors-UU book illustration festival. At Lake Baikal, in the village of Ust-Barguzin, another independent initiative called Bargujin Tokum has been supporting artists and hosting art-related events and festivals which are organized by Kheb-Hub. Operating as an art residency, it regularly puts on plein air painting sessions for local artists and calligraphy workshops.