Natalya Nesterova: My work is about what you see

Natalia Nesterova. Courtesy of artinvestment

Emigrating in the late 1980s, Russian painter Natalya Nesterova’s extraordinary talent found a receptive audience in the USA. Gallerists Hal Bromm and Alexandre Gertsman promoted and represented her there, staging many exhibitions across the USA over three decades. They write about their memories of her, and how her work needs no explanation to be understood.

Hal Bromm

Meeting at Kennedy Airport in 1988, somehow finding each other without benefit of mobile phones, Natasha arrived with a painting in hand. It was a gift for me, a thank you for bringing her to the USA for our first exhibition together at my gallery. The exhibition was a big success; the introduction of Natasha’s work to America was well received.

Through Natasha I was honored to meet many important Russian artists who were her close friends. What was interesting to me was that she was nearly the only woman among a distinguished circle of men including Grisha Brushkin (b.1945), Alexander Kosolapov (b.1943), Leonid Lamm (1928-2017), Vasily Komar (b.1943) and Alexander Melamid (b.1945), Ilya Kabakov (b.1933), Leonid Sokov (1941-2018). It was obvious that Natasha had enormous respect among her male peers.

In August 1991, Natasha and her son Lev were staying in my New York apartment just as communist hardliners and military elites tried to overthrow Gorbachev in failed coup. Terrified as to what might happen, they watched the turmoil unfold on TV. That moment seemed to signal a dramatic change that left Natasha rather shaken. Our planned visit to Moscow together was put off and has sadly never happened. This drama may have led her to acquire a New York studio near Carnegie Hall, where she could enjoy concert performances and savor the sophistication and magic of the city.

Natalya had her first Chicago exhibition in 1991, and the following year an exhibition in Madrid. In 1992 a major retrospective organized by Louise D'Argencourt, guest curator at the Musee des Beaux Arts in Montreal opened. Natasha and I travelled to Montreal for the vernissage, and I remember at the Press Preview one of the reporters asked Natasha a question, seeking to know what her work was ‘about’. Her reply stays firmly in memory: “My work is about what you see”. Indeed, art invites us to bring our own response to what artists create. Art should be allowed to speak to us without always needing an explanation.

When Natasha was asked by her mother to raise her grandson David, she brought him to New York, and they came to stay at my country home. I remember David as frightened small boy, perhaps seven or eight years old. Time flies, and recently we joined Natasha to attend David’s university graduation, where his grandmother proudly watched as he received the highest honours in his class. Now a brilliant young man, David faced Natasha’s hospitalization and death with strength and courage. That serious ordeal forced him to accept full adult responsibilities far too soon.

Over many decades working together, Natasha has been a beloved family member and very dear friend. As we mourn the death of a brilliant artist and loving friend, Natasha will be deeply missed in ways that words cannot express.

Alexandre Gertsman

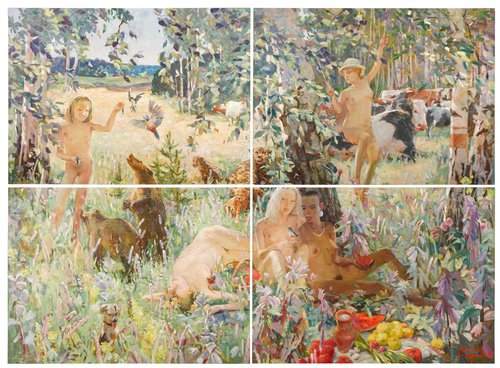

I saw Natalya as a brilliantly coordinated orchestra with an array of instruments obeying the conductor's magisterial hand. She was both a luminary and a maverick, who emerged amidst the world of rapid cultural change of Perestroika of the late 1980s but whose imaginative works imbued with an unapologetic reactionary nostalgia of an ideal past, works refreshingly void of political and aesthetic rhetoric, unusual for Russian art of the era.

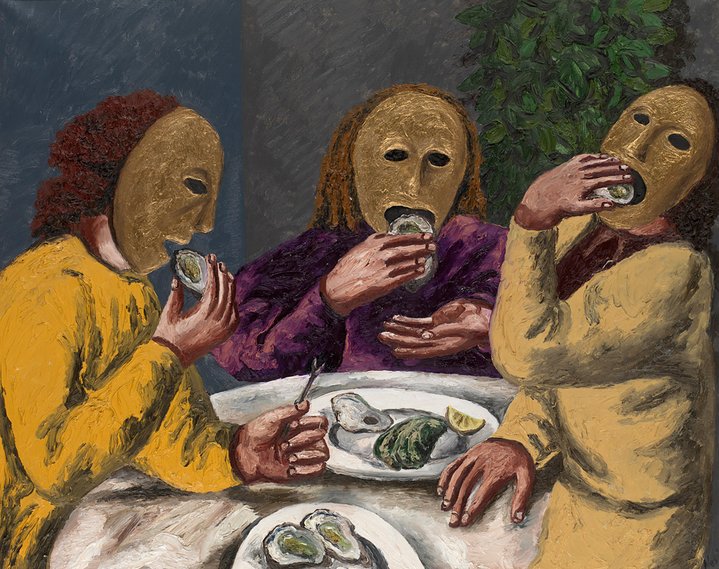

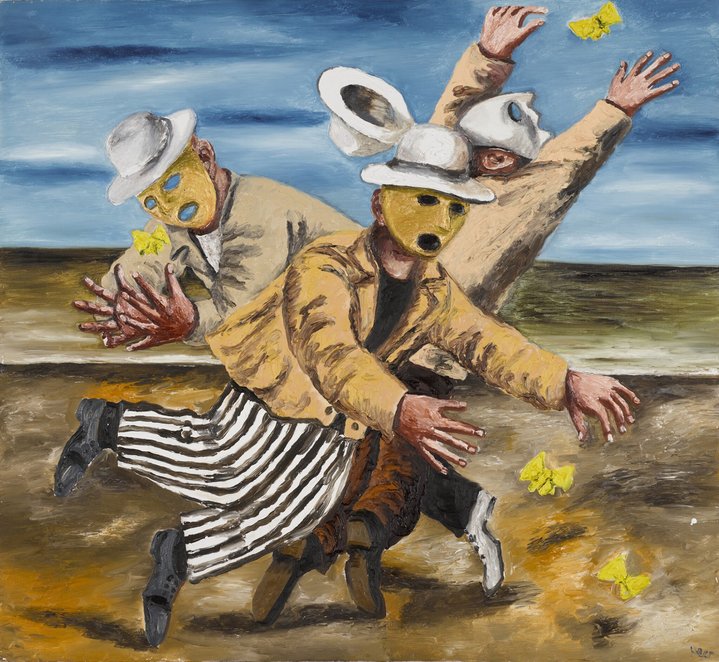

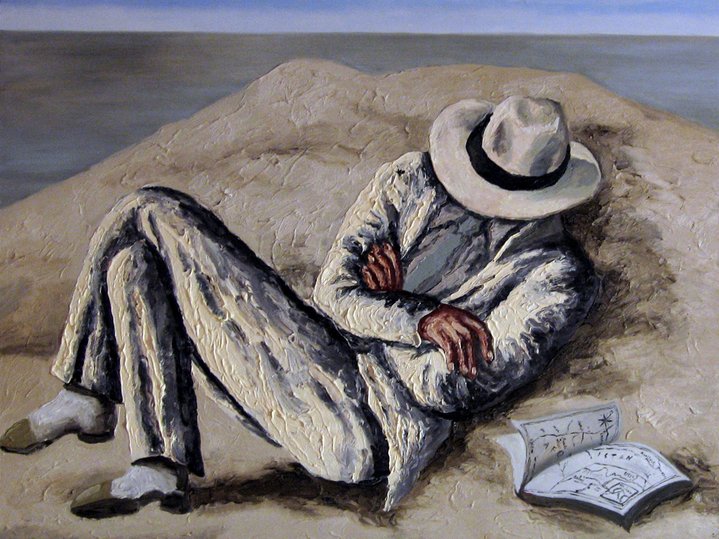

There are artists whose works are literal and transparent, which makes them easy to read by viewers. In Natalya’s case, her ideas were only known to her, which in turn made her work even more intriguing. Sometimes collectors of her work would tell me that they discovered new meanings in her paintings years after they had acquired them. Mystery is something which defines art in general, and her art fully represented it. There was always a twist, a little joke, a hidden motive. Besides, her work is highly theatrical. One single painting may contain not just a plot line but an entire story.

Natalya loved working, she painted every day, and home for her was any place where she set up her easel. From 1994 until 2009 we would travel around the United States together for the exhibitions of her work I organized in different museums and universities, and when she was separated from her canvases and paints for more than a few days, she became anxious. For Nesterova making art was as natural as breathing. Although you can find some of her deepest feelings in her paintings, she did not care to show her emotions in public. She often experienced feelings of despair, she used to talk of living with hell inside her, but that she would never share it with anyone. Natalya was extremely critical of herself. She disliked attending her exhibition openings, she didn’t like looking at her own paintings on display. She rarely talked about her work and after saying a few words to the public assembled at an opening, she always asked me to take over and talk about her and her art. She also detested being asked what she had painted. She found such questions strange, for it meant perhaps that the person did not understand her paintings at all, or that she herself was not able to say and deliver anything she had meant, to her disappointment.

She painted very fast, but when she was working, I sometimes saw her spend most of her time just looking at the canvas, figuring things out in her head. In later years she felt that she had been painting for so long that she no longer needed to try out her ideas on the canvas. She could just look at the canvas and would know instinctively whether something was going to work or not. She would say that when she sat in front of the easel looking at a canvas, this was also work. She was constantly engaged in a creative process, each one of her paintings was a finished artistic product of an integrated, lengthy, internal creative process. Natalya also believed that painting itself, done quickly, with impressions still fresh in the mind can make a painting more alive, more thrilling. Once she finished a brush drawing on canvas, at that stage she considered the work pretty much compete. What remained was the colour, which she often had thought through ahead of time, but which could change along the way. And what I called, in our conversations, a rare gift – to be able to say and define everything in a sketch – she modestly called nothing but a craft and skill.

Nesterova’s first public exhibition in a young artists’ group show was in 1966, but she dated the start of her independent artistic career to 1969, when she graduated from the Surikov Art School in Moscow. She always said the most important teachers in her life were her grandfather, an artist, who drew beautiful amusing pictures for her and who taught her everything, and her parents, who were architects. Her best, closest, most sensitive and respected of all her critics was her mother Zoya, and probably nobody understood Nataya’s work better.

Natalya was never part of any art group or movement, but a free spirit, surrounded by a group of artistic friends, united by similar philosophical and cultural ideas. At first critics threw her together with primitivists and realists, and for many years, this was how she was classified as an artist. Later, critics would just say: ’This is Nesterova’, and then put her into whatever category they chose. She always ‘classified’ herself as ‘Natalya Nesterova’. It is not surprising that national recognition followed her; she was nominated an Academician and Honorary Artist of the Russian Federation. She received the National Award in Fine Arts, the Triumph Award and the Gold Medal of the Academy of Fine Arts in Russia. Her artistic accomplishments have crossed social and cultural borders, since 1988, when her work was included in Sotheby’s legendary auction in Moscow. She subsequently became one of the very few female artists from the late Soviet period to have a consistent presence on the international auction market in London and New York.

Nesterova has been nationally and internationally featured in over a hundred solo and collaborative exhibitions, and remains part of the permanent collections of the world’s most recognized museums including Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and The Jewish Museum, both in New York, the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., Ludwig Forum for International Art in Aachen, The Russian Museum in St. Petersburg and The National Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of Contemporary Art in Budapest, and China National Museum of Fine Arts in Beijing.

The culmination of a life devoted to art is chronicled within her works which intimately communicates an artistic percipience and ingenuity that is truly Natalya Nesterova. She left behind an enormous body of work, which will continue to captivate us for decades to come.