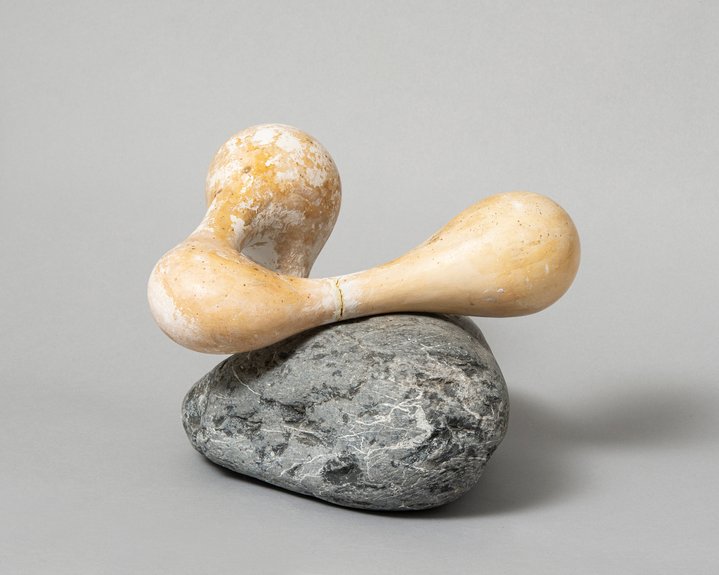

Maria Bartuszová. Folded Figure, 1965. Collection of Amy Gold and Brett Gorvy. © The Archive of Maria Bartuszová, Košice

Maria Bartuszova, the artist who makes broken eggshells

The rediscovery of long forgotten female artists today is a top priority for both international museums and auction houses and an exhibition of Slovak sculptor Maria Bartuszova has just opened at Tate Modern in London. Her fragile forms are the perfect expression of art for our unsettled times and show us how to reconnect with nature.

This first ever international solo exhibition of sculptor Maria Bartuszova (1936–1996) had a few false starts. Initially slated to be shown alongside the Tate’s Rodin exhibition in 2020, it was postponed because of the pandemic. At the opening night, also postponed due to the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, Tate Modern’s director Frances Morris mentioned that even the exhibition space had to change on several occasions because of the rescheduling, a nightmare for any curator. This may have been why the works were placed mainly in tall cabinets under Perspex covers clustered around in a few large rooms. However, this also gives visitors the chance to look through and survey a whole room full of works in one gaze. Just how does this body of work stand such scrutiny?

What collectively could easily produce a sense of monotony with the artist’s persistent use of white, and repetition of forms created often on a modest scale gives way to an almost mystical experience. I did not know which way to look, and left to my own devices, wandering through this light, airy space the works invited me to engage with them. ‘Shapes capture psychological states’ wrote Gabriela Garlatyova curator at the Bartuszova archive in the catalogue essay and Bartuszova’s emotive biomorphic forms undoubtedly stir and move those who stop and look. The artist herself liked to show them sitting on the floor or on low wooden tables which could have been created in this exhibition by way of a smaller, internal constructed space within a space.

The curators refrained from a lot of geographical or art historical contextualising, perhaps surprising with an artist who people have not heard of, yet this crucially showed just how universal Bartuszova’s art is. I went away with the impression that this body of work could have been made not half a century ago but today and anywhere. Bartuszova is certainly not yet a household name even for art historians, and Tate Modern has led the field in introducing little-known artists from the periphery into the mainstream. This is a liberating cultural experience not only for the artist’s legacy giving it a new platform, but also for exhibitiongoers who can approach great art with a blank slate and few expectations.

During my visit on the opening night, I learnt that Tate’s REEAC committee which previously included Russia in the acronym has recently refocussed more on Eastern and Central Europe in a direct response to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The word of the moment at Tate is now ‘transnational’: an approach focussing less on art from specific nations, but on broader trends and movements which cross borders. Although an insistent focus on geography which started at the beginning of the noughties to address national imbalances in art history has in part resulted in bringing the Maria Bartuszova show to London, her work surely expresses something far more deeply in tune with our times than just the rediscovery of another little-known female artist from Eastern Europe.

In postponing the exhibition until now, there is a sense that there is something familiar in Bartuszova’s life story which unfolded during the period of immense political turmoil in Europe in the middle of the 20th century. She was born in 1936, her mother was of German descent, problematic during the Nazi occupation of what was Czechoslovakia and her Fernhill coincided with the horrors of WWII. Later she moved to Kosice in present day Slovakia close to the border with Hungary and the Ukraine, and as a teenager she witnessed the Soviet occupation which was to remain until close to the end of her life. It is hard not to see something of these huge social and political shifts of her formative years in her preoccupation with the fleeting nature of life, of its fragility and how she turned to look at what is immutable in life: the very essence of mutability.

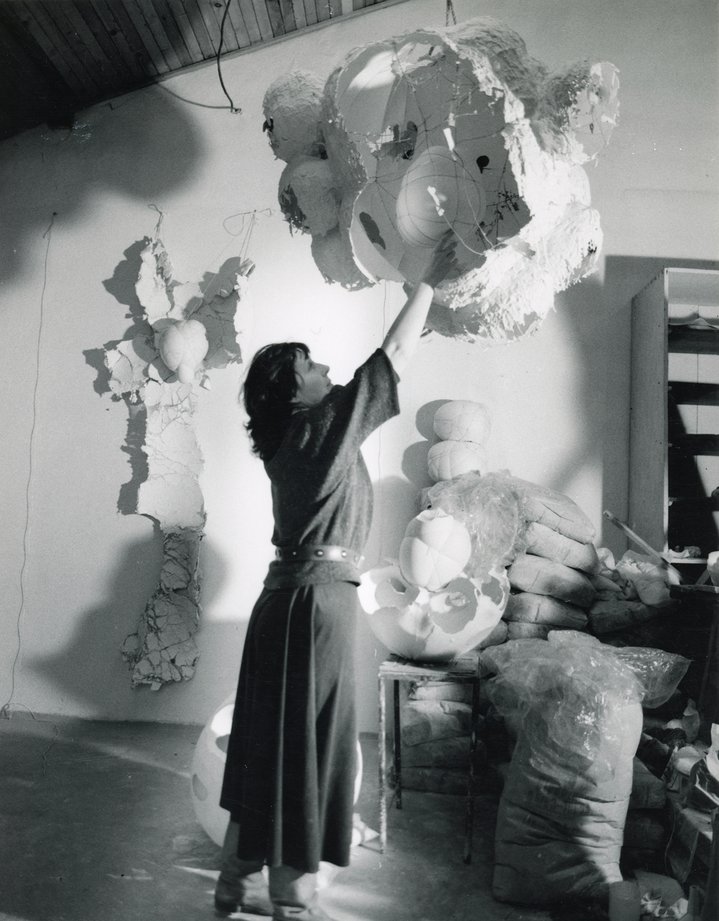

Through Bartuszova’s mature work, which the Tate show bookends from the early 60s till the late 80s, you can trace the natural dynamics of growth and decay in organic forms drawn from nature. In some of her egg sculptures, such as Endless Egg (1985), she tries to capture both forces in one: with pieces of broken eggshell bursting out of an otherwise nearly intact egg, appearing to multiply and grow out of the cavity. More simply put are those works which imitate fragile husks of broken eggs, which give the suggestion of life having been lived and left. These she would create as bas-reliefs to be displayed on the wall, with no titles, such as the work from 1985 which the artist’s estate presented to Tate in 2016. This use of empty shells also represents a key strand through her work where she explores and plays with voids. There is a series of small and medium scale sculptures in which she has blown air into a balloon, covered it in plaster and bound it with something as simple as string; the results no longer containing her own breath, trace and leave us with the processes of creation in atrophied form.

The great modernist sculptors such as Henry Moore (1898–1986) and Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) were pioneering in creating biomorphic art into a style to which today most people can all now relate. What Bartuszova does is take this a step further making works recalling forms and shapes found in nature by using processes which themselves are subject to forces of nature, whether using her breath or experimenting with gravitational pull. This feels very much of our time where there is an ever more urgent need for us and our communities to reunite with nature. Bartuszova’s art practice reaches out inviting us to reflect on our own relationship with nature and its laws. We are as much bound by them as the string tied around her white plaster husks.