Andrei Pokrovskii. MM Realm, 2020. Oil on wood. Courtesy of andreipokrovskii.com

It’s a surreal life for young Russian artists

There is a taste for surrealism today among millennial Russian artists. Art critic Sergey Guskov explores the roots of this phenomenon.

It was eighty years ago that the sun set on the art movement known as Surrealism, yet this historical and cultural phenomenon with its charismatic figureheads and distinctive aesthetic has endured a continous legacy since then throughout the world. A more recent wave of interest internationally started around a decade ago, and is now on the wane, but its traces can still be seen everywhere, and it has peaked in the main project of the current Venice Biennale, curated by Cecilia Alemani inspired by the work of Leonora Carrington (1971–2011).

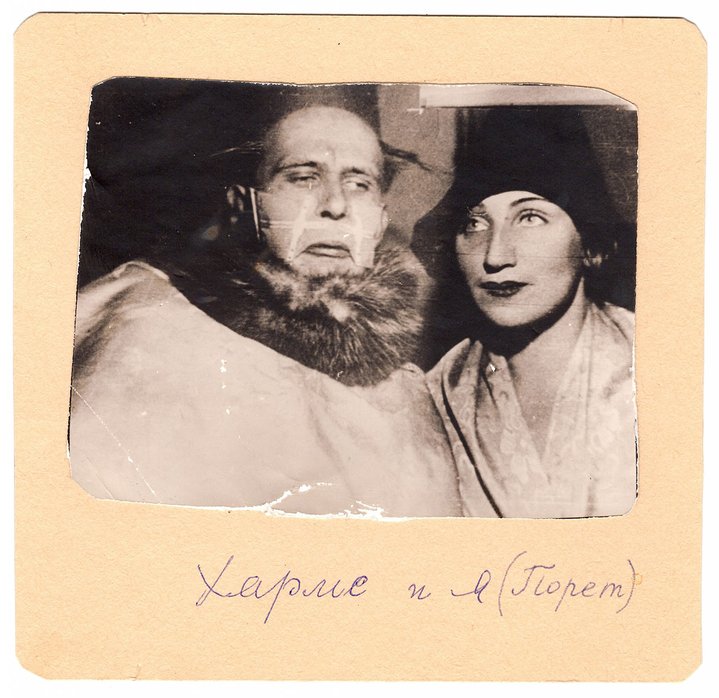

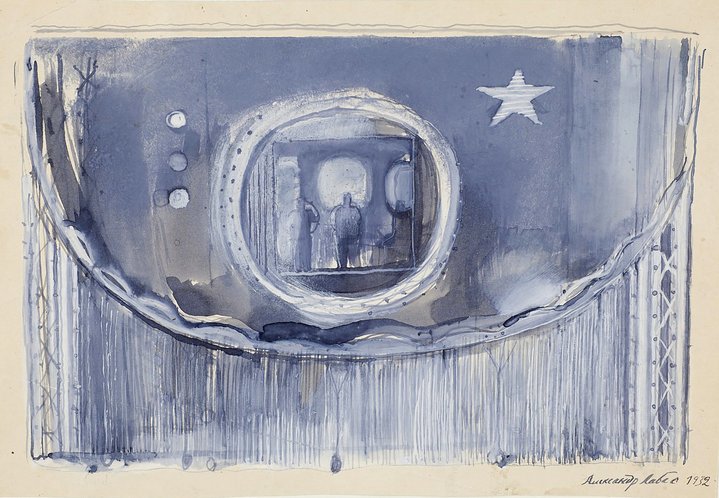

This fascination for surrealism started in Russia later, in a watershed moment in 2016. A manifesto by critics Alexandra Novozhenova and Gleb Napreenko called ‘Weak Resistance’, was published in the 11th issue of the online magazine ‘Divergent’. The writers flagged up the the liberating and pacifist potential of Surrealist artistic strategies and revealed its paradoxical presence in both Socialist Realism and late-Soviet unofficial art. In Spring of the following year, gallery ‘Na Shabolovke’ in Moscow held an exhibition called ‘Surrealism in a Bolshevik Country’ curated by Aleksandra Selivanova and Nadia Plungian, which, according to its organizers, raised the question of the existence of an artistic language close to Surrealism in the unofficial Soviet art of the 1930s and 1940s. The work of Meer Eisenshtadt (1895–1961), Boris Golopolosov (1900–1983), Vera Ermolaeva (1893–1947), Pavel Salzman (1912–1985), Alexander Labas (1900–1983), Alexei Pakhomov (1900–1973) and Alisa Poret (1902–1984), and many others were examined from a new perspective.

These two references to Surrealism, a movement whose influence had never before been accounted for in Russian art of the period, set in motion a discussion with is still running today. And one other consequence of this discussion was a growing interest among contemporary Russian artists for Surrealist aesthetics.

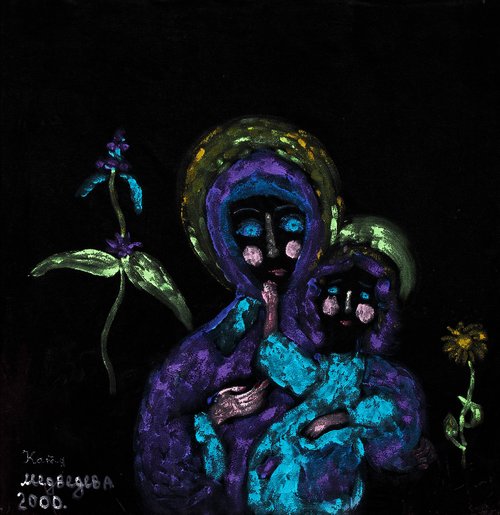

Artist Anton Kushaev (b. 1983), graduated from an icon painting school, and working with various forms of religious art, was inspired in parallel by the visual traditions of metaphysical painting and Surrealism. ‘My first illustrated album was a history of Surrealism’, the artist explained to Russian Art Focus. ‘At 13 I read 'Diary of a Genius' by Salvador Dali. When I was 14, one of my favourite poets was Paul Éluard. Surrealism for me was something of a school, and from it I gradually began to understand the contradictory nature and enormity of the world of images. Iconoclasm as well as apophasis are part of the other side of this understanding. Now we have a new wave of Surrealism, and it has a different artistic agency: it is technogenic and there is a preoccupation with the nature and spirituality of materials’. Kushaev's recent paintings can be read as deconstructed icons, where faces consist of architectural elements and even have crutches borrowed from Dali.

Diana Kapizova (b. 1993) creates videos that may be short but are monumental in mood and composition, in which she refers to a wide range of images, symbols and legends. ‘In her works created with the use of 3D graphics, poetry, singing, music, dance, and animation, she creates an original form of psychoanalysis with classical roots’ explained curator Svetlana Taylor, who has been working with the artist for some years. ‘Finely attuned to the meta era with a grasp of virtual, unreal, and hyper realities, she combines all kinds of different digital aesthetics, conceiving her works as theatrical shows. She plans out the scenography and dramaturgy carefully yet viewers are given space for their own interpretations’. Kapizova's work weaves together Freudian and Jungian notions with psychedelic patterns. There are shells, caves, fish playing musical instruments, underwater journeys, exploration of life-after-death states, a deer that magically appears from a rug; birth and rebirth. The protagonist is usually the artist herself, and she goes through constant transformations.

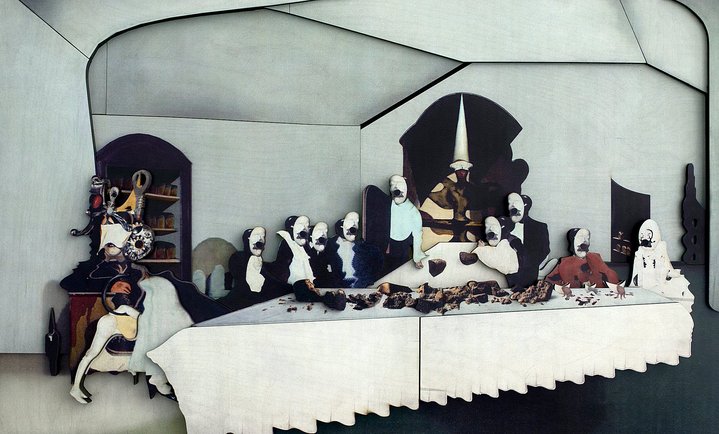

Painter and graphic artist Andrei Pokrovskii (b. 1996) employs with classical subjects from art history. His works are reminiscent of textbook illuminations, like fine Renaissance paintings, which have undergone fantasmagoric mutations: the colour scheme is distorted, the actions of characters, once bound by a canon, are divested of their original meaning. Pokrovskii particularly likes using wood for its mobility and its reliability as a material. At times, he literally falls under the spell of a particular image which he reproduces in different guises. One series, for example, is dedicated to beehives. It is an approach which is partly reminiscent of the automatic writing of the Surrealists.

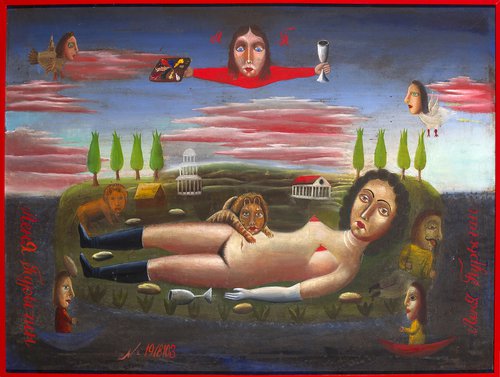

Katerina Lukina (b. 1995) also turns to a pure, classical heritage for inspiration. Her disturbing doll like images a la Rembrandt involve multi-figure compositions, as well as the light and colour solutions typical of 17th century Dutch painting and she ‘imposes’ a surrealistic ‘filter’ on the resulting images.

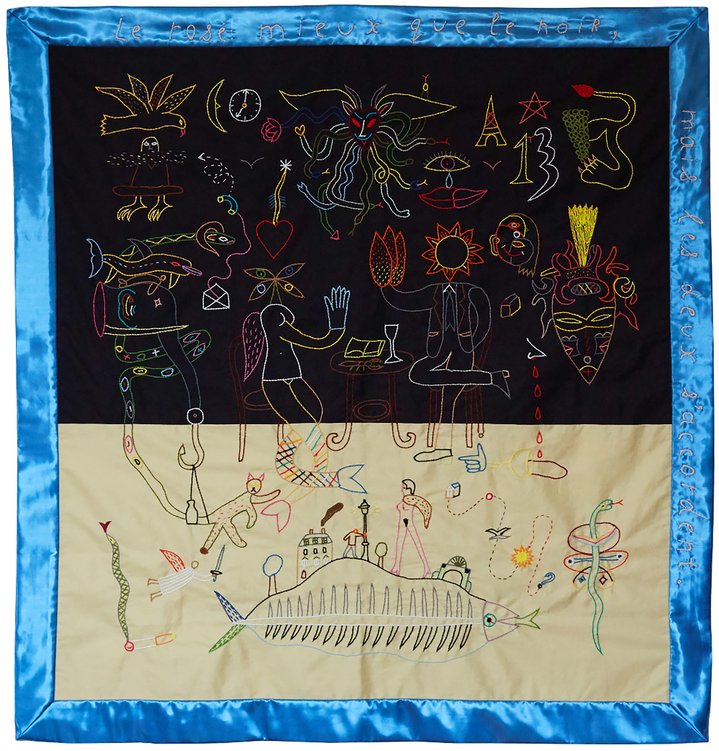

Rodion Kitaev (b. 1984) has also been influenced by the legacy of Surrealism, particularly artists such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo (1908–1963) and Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012). There are several figures in his paintings, drawings and embroidered fabrics, who are interacting with one another, engaged in copluating or devouring one another. These characters do not represent one particular biological or anthropological species, but rather are embodiments of desire with its effect.

‘We can talk about a renaissance of Surrealist aesthetics,’ Gleb Napreenko told Russian Art Focus. ‘I would centre this trend as follows: in each of these artists, the question of the human body, in plastic form and with its libido, is key. It is not a body we know from the classical tradition of representation where it is depicted in a specific discipline. In Surrealism, the body knows how to enjoy itself. In each of these artists the body, as it is portrayed, is not perfectly shaped, it is blurred, split up into fragments, sub-bodies, organs, which in turn grow and are each filled with their own particular pleasures which interact and intermingle. It is a strange existence. The body fights the harmony which has been imposed with haunting and amusing effects. Either way, this is a body which is fulfilled in life. In the current context, one can see a political charge in these works (although without a direct statement), against the normalization of body life. And also against militarization, because war presupposes bodies that march in formation, obey orders, and are subordinated to a single impulse. Surrealist bodies rise up, driven by their passions’.