It used to be a Gulag: Artists on Memory and Forgetting

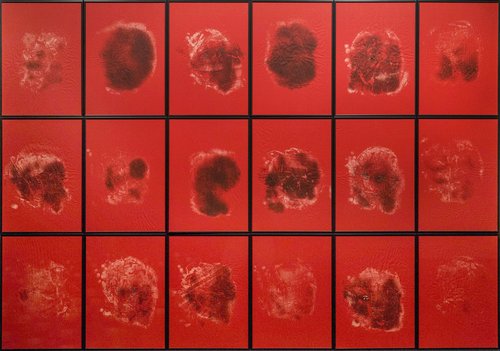

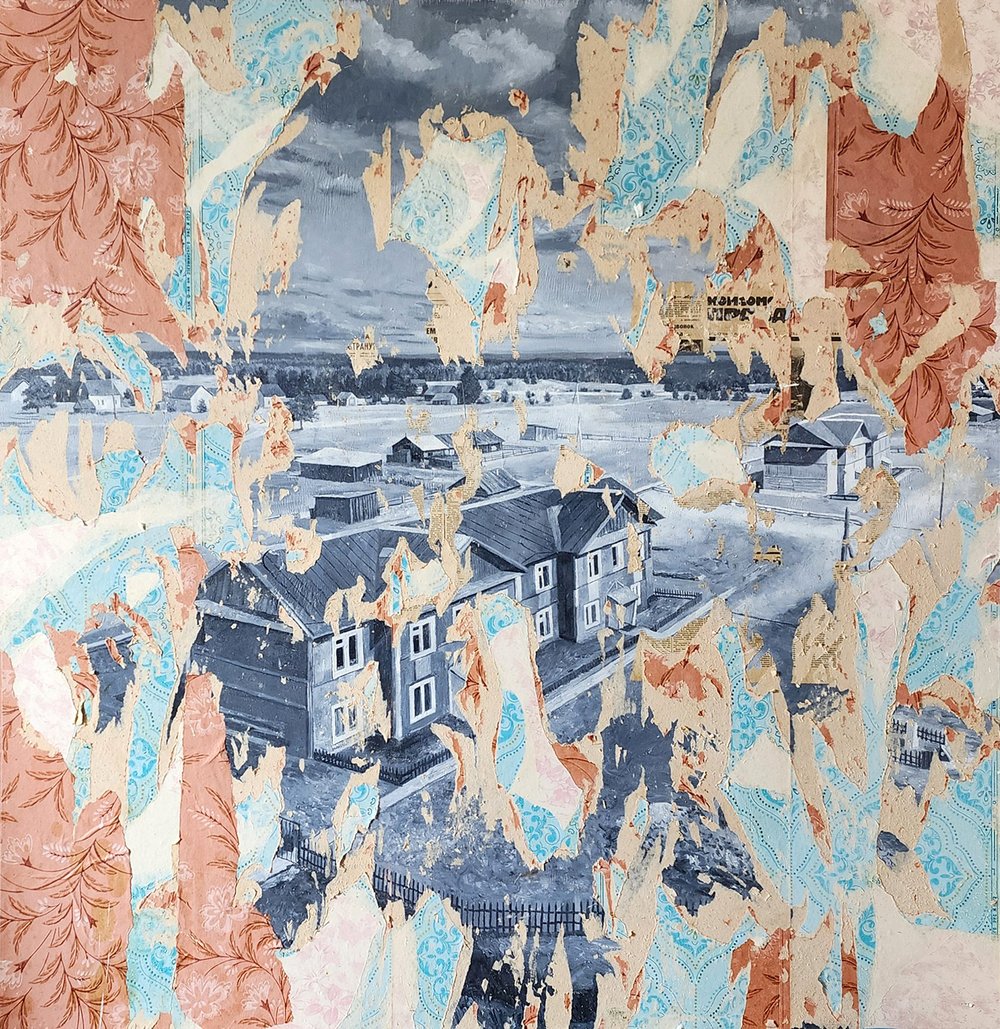

Vladimir Potapov. Adzherom. Type: Settlement. Status: Residential. Photo courtesy of Zverevsky Centre for Liberal Arts

An exhibition of Moscow based artist Vladimir Potapov tells the story of a former labour camp which was turned into a rural settlement where today numerous families of both former inmates and guards live side by side. It is part of a wider trend of contemporary artists in Russia who are revisiting the sites of Stalin’s mass repressions, wrestling with the difficult legacy of memory and forgetting.

When the Gulags closed down, most were left abandoned. Their ruins crumbled and the unmarked graves of the victims were taken over by the taiga. However, Adzherom a small, remote settlement in the Komi Republic, 1,300 kilometres to the northeast of Moscow, is a rare exception. During the 1930s tens of thousands of prisoners were sent there to chop down trees, a punishing job because they were only given hand saws and axes, the trees were huge and they did not have clothing suited to the extreme cold temperatures in winter. Many never returned, they were either shot or died of hunger, cold and hard labour. The last remaining camps in the region were closed in the 1950s, but by then the inhabitants did not want to leave and the camp buildings were converted for civilian use. Former prisoners and their guards continued to live alongside one another, even raising families together and their grandchildren still live there united today by a shared reluctance to talk about the past.

This strange and chilling history of Adzherom has captured the imagination of Volgograd-born, Moscow-based artist Vladimir Potapov (b. 1980) and he travelled to Komi to see it for himself. He walked around with local history buffs, paid his respects to the mass graves scattered through the forest and was even invited to have a cup of tea in a former prison, now a private home. “In the house there were windows between each room which were made so the guards could keep an eye on the prisoners. The current owner of the house did not seem to mind these windows at all,” he recalls as we talk together about his journey at the opening of his solo exhibition ‘Adzherom. Type: settlement. Status: residential’ at the Zverevsky Centre for Liberal Arts in Moscow

“The place tries hard to look like a normal settlement, but its uncomfortable past sticks out at every turn”, he says. The artist even invented a new painting technique to convey a sense of the sinister to his audience. He painted the village scenes in oil on large sheets of plywood covered with a special substance: the paint bursts and peels away, revealing the empty spaces underneath. Sometimes he covered the sheets with several layers of Soviet wallpaper and tore them off to reveal the former camp buildings painted underneath. For Potapov, Adzherom is a living metaphor for Russia as a whole. “This is a miniature model of a modern society where there are radical disagreements, where there are very serious contradictions,” he believes. “Unlike other countries, we have not dealt with our past, and this unprocessed past continues to affect the present. Potapov speaks from personal experience. The Adzherom exhibition was recently banned from the Museum of Gulag History in Moscow because the artist's name appeared on some blacklists, a form of censorship common in Russian state and municipal museums these days.

In Russia, buildings and places seem to have a longer memory than people. Perhaps this is why the artists of the first post-Soviet generation are drawn to such buildings and places – silent witnesses to the troubled past. This obsession is reminiscent of Romanian scholar Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory. According to her, events that happened long before we were born can haunt us like our own childhood traumas, and pain can be passed down from one generation to the next. The writer Maria Stepanova was the first to apply it to Russian material in her non-fiction family saga ‘In Memory of Memory’. Russia has always had an uneasy relationship with its past, forgetting, digging up and rewriting it. The most well-preserved Gulag in Russia is Perm-36, near the city of Perm in the Urals. Political prisoners were held there until as late as the 1980s. After the collapse of the communist regime, it was turned into a museum. Perm-born artist Anna Andrzhievskaia (b. 1989), whose maternal grandfather and paternal great-grandfather survived the Kolyma camps, became interested in the place and its macabre history. She depicted the camp's buildings in her project of 2012 ‘Fencing System’, capturing the claustrophobic atmosphere of the place in small dry-point needle prints. The fate of the museum itself is emblematic. Launched as an independent non-profit in the 1990s, it was taken over by the government in 2014, and the new management shifted its focus from political repression to the history of law enforcement. Former camp guards were hired as guides, according to journalists who visited the site after the transition.

Unlike Andrzhievskaia, Danila Tkachenko (b. 1989) did not go to the confines of camp fences but to the vast, snow-covered tundra to try to retrace the footsteps of gulag victims. There, he defied the power of time and oblivion to erase painful memories from the landscape and from history itself. For his project ‘Mannequins’, Danila Tkachenko placed mannequins covered in black cloth on the sites of former labour camps in the far north of Russia. The artist is fascinated by abandoned buildings that have outlived their inhabitants and their purpose - Soviet military bases, empty apartment blocks, ruined village churches and dachas - and has captured many of them in his photographs. But in ‘Mannequins’ he turns his camera to places where nothing remains, where the last ruins have rotted away and the landscape looks deceptively innocent. The absence of monuments and memorials in these places seems deliberate to him. “The Russian state, the immediate successor to the Soviet regime, does not want to acknowledge its guilt and tries to conceal the vestiges of the crime,” the artist says. In his photographs, the black-clad figures look like restless ghosts, trudging along snow-covered hillsides where their bones lie in unmarked graves. “Russia is a country where millions of people remain unburied. This incompleteness is one of the reasons why the recent past continues to haunt Russian politics and cultures, to divide society and place restrictions on political choice,” Tkachenko notes in the description of this project on his website.

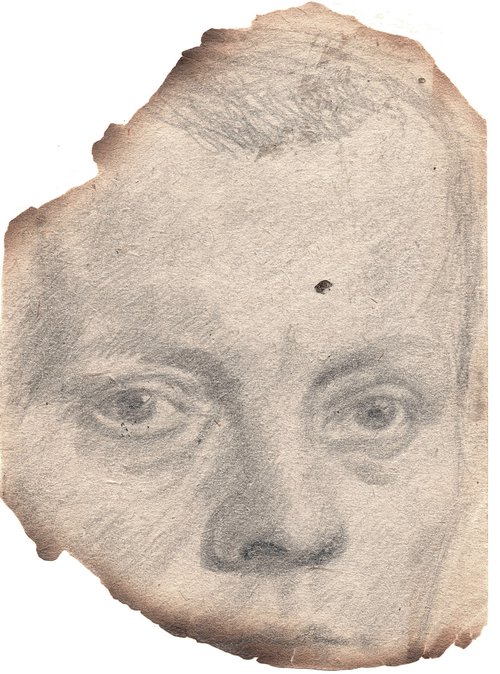

But words outlive buildings, and a poem often proves to be a more permanent memorial than a tombstone. Olga (b. 1967) and Oleg (b. 1966) Tatarintsev have based their project ‘Beyond Borders’ (alternatively called ‘Freewords’) on quotations from Russian poets and writers who spent part of their lives in prisons and labour camps. All the extracts are taken from works which were written in prison. Among them are passages by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Osip Mandelstam (who died in a Gulag) and even theatre director Kirill Serebrennikov, who spent eighteen months under house arrest. First shown in 2018 at Moscow’s pop/off/art gallery, the Tatarintsevs’ project has a strange resonance with Indian artist Shilpa Gupta’s (b. 1976) installation ‘For, in Your Tongue, I Can Not Fit’, which was presented at Baku’s Yarat Centre earlier that year and shown simultaneously at the Venice and Koichi Biennales in 2019. Gupta’s minimalist installation was simply a room full of loudspeakers playing poetry in various languages, with sheets of printed poems on sticks for visitors to peruse. The lines belonged to a hundred poets who had been imprisoned over the centuries for their writings or political leanings. The Tatarintsevs’ work also includes loudspeakers but is aimed more at the audience’s eyes than their ears. Each quote is transformed into a powerful visual statement with bold, poster-like fonts and partially obscured lines, as if scratched out by prison censors. The artists’ warning is even more relevant today – as long as we choose to ignore the past, it will keep repeating itself.

Vladimir Potapov. Adzherom. Type: Settlement. Status: Residential