In Yakutia: Postcolonialist art as Neoshamanism

A survey of Yakutia’s contemporary art scene called ‘Save Up Laughter for Winter…’ has opened at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art and will run until 9th of October 2022. This cold, remote region in the North-East of Russia has asserted its presence in the nation’s cultural landscape.

A quick search on Google in Russian for MOMA gives 1,800,000 results, for MMOMA (the Moscow Museum of Modern Art) 129,000 results, for MOMA New York about 82,100 results and for Moma Yakutia around 12,400! Moma is a river, the right tributary of the Indigirka. Even by Yakutian standards the Moma Ulus is a remote part in the north east of the republic. It stretches over a vast area some 100,000 square kilometres in size, larger than Portugal or Hungary, yet in 2021 it was home to just 4,051 people.

‘Radio Moma’ created in 2022 by artist Sardaana Khokholova (b. 1993) is a work about homophony, in which she explores how the known supersedes the unknown, or the familiar, the unfamiliar. “Radio Moma consists of recordings from a local radio station with voices of Moma residents, a mix of songs and conversations. At MMOMA, the exhibition visitors listen to the audio tracks from Moma, but they can not understand what is being said or make out the words in the songs; words turn into music, speech into rhythm. European pop takes on local colouring and all that the ‘Other’s’ ears can catch is couleur locale.”

Yakut (Sakha in the local language) culture is well known to Russian audiences. Cholbon, a band from Verkhne-Vilyuysk, conquered the scene in the late 1980s with their combination of tambourine, howls, melodeclamation and throat singing with electric guitars, saxophone and drums which gave rise to Yakut rock, triggering a wave of new ethno-rock. The Sakha Theatre named after P.A. Oyunsky, the Sakha Republic Opera and Ballet Theatre and the Olonkho Theatre are regularly seen in Moscow for the prestigious Golden Mask theatre festival. So Muscovite theatregoers have long been hearing stories about shamans and udagans (female shamans), and aware that Macbeth could be a story of the struggle between the world of the living and the world of the dead. A quarter of a century ago, Olonkho Theatre’s groundbreaking production of ‘King Lear’ directed by Andrei Borisov sparked off a revival of national theatres across Russia.

An entire issue of the magazine ‘Art of the Cinema’ was given over to Yakutia's cinema in 2021 as Yakutia has probably the most developed ethnic film industry in the Russian Federation. ‘Scarecrow’ (2020) a film about an alcoholic female healer, shot by Dmitri Davydov a village primary school teacher in just eleven days, received international acclaim and won the top award at Kinotavr, a leading Russian national cinema festival.

Unfortunately, contemporary art from this region is less well known in Moscow, and little known at all outside Russia. Neo-shamanism and reflections on postcolonialism are the two foundation stones of this new exhibition ‘Save Up Laughter for Winter…’ at MMOMA. It presents the work of a dozen artists and one art group.

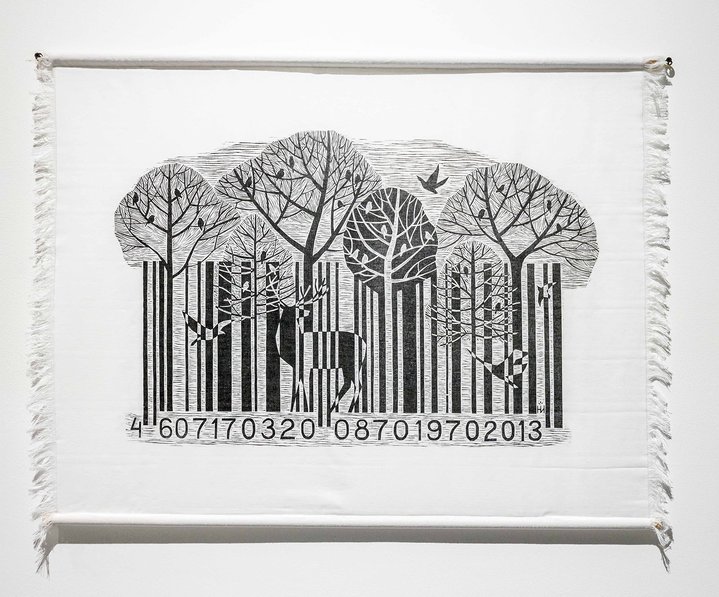

Yakut artists often use pseudonyms. For example, Anna Petrova (b. 1973) is called Karehit (meaning, Witness), or Kyunnei Ivanov (b. 1988) aka Ian Sur. In this tradition an artist is a kind of shaman requiring a special name, and where art is a sacral practice. An artist reflects back timeless feelings about human loneliness experienced in the midst of boundless nature with its eight months of winter, a world in which humans are however constantly surrounded by spirits. When contemporary Yakut artists refer to their ancestors they mean the peoples who inhabited the Eurasian steppe for thousands of years. Most artists preserve the original titles of works in the Yakut language as a matter of principle

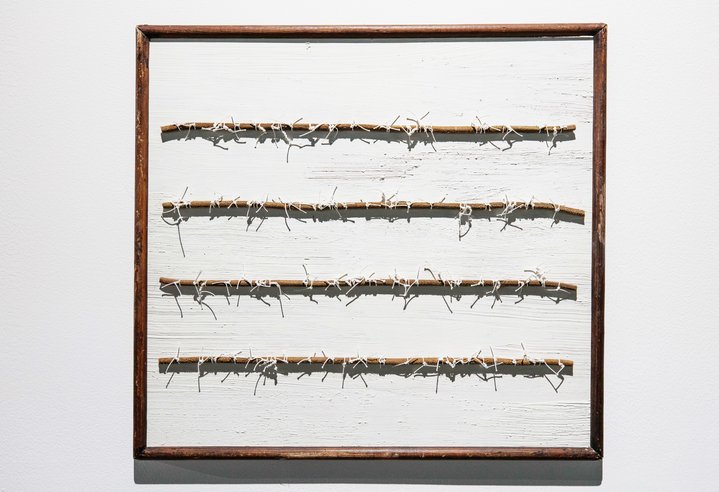

Olga Skorikova (b. 1963) makes calendars out of improvised materials. In ‘Setin-olunnu. Turgutuu’ (meaning, ‘From November to February’), produced in 2021, four leather cords are attached to a painted, organically sourced board: a cord for each month, and one knot of white thread means one day. Four winter months are turned into a landscape of knots and cords on white acrylic ‘snow’. The ancient tradition of knot-writing is a source of inspiration. ‘Beliye kun. Kulue tutar’ (meaning, ‘March 2023’) is a calendar for a month yet to exist in the future, made of coloured beads which bring positive expectations.

In her assemblages, Karehit attaches leather, metal and embroidery to pieces of cloth, reminiscent of Japanese scrolls or Timur Novikov’s (1958-2002) textile collages. Found items scavenged from rubbish dumps, such as an iron spring, are combined with a painted leather image depicting two fantastic winged animals, their horns intertwined in the spirit of the Scythian animalistic style. Rusty iron birds are stitched onto a lilac canvas next to equally rusty odd and apparently useless technical objects. When placed in a mythological context, industrial things take on new meanings and reveal dimensions which lie beyond their immediate function. ‘Yakut Povera’ art refers to both arte povera and the Japanese principle of wabi-sabi.

The neoshamanism of new Yakut culture is part of the new age ideology: it is syncretistic, drawing its inspiration from different sources. However, neo-paganism in Europe is based on a long forgotten tradition revived from oblivion. Neoshamanism in Yakutia grows out of traditions that were in fact still alive in the time of the great-grandparents of those who are today researching and following it. Because of this, it is a more active instrument of postcolonial reflection. The shaman turns out to be a figure who was destroyed under Europeanisation, but, it seems she/he can return. At least in the form of an artist.