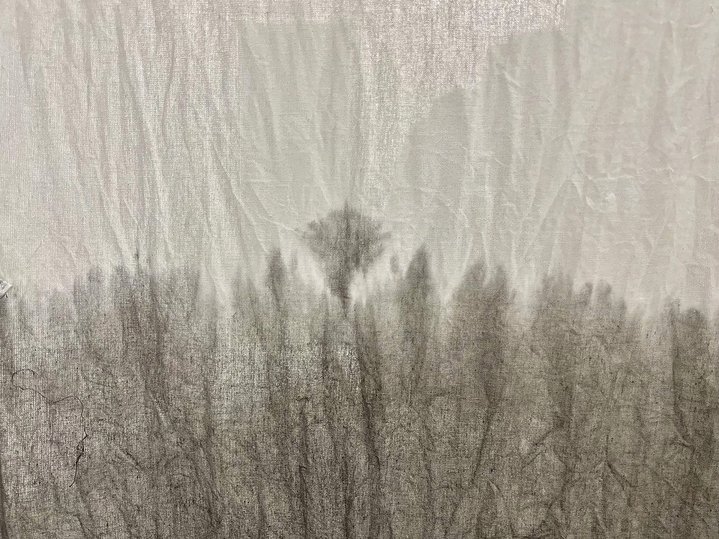

Mikhail Rubankov. 'Room 304' at the Marco Polo Hotel. Moscow, 2023. Courtesy of Nakovalnya Gallery

Immersed in Art: Artists Rethink Total Installations

There is a renewed interest in total installations among young artists in Russia. Is this a desire to escape from a depressing reality and construct a smaller but better world, built out of dreams and memories?

The genre of total installation, its origins often associated in the West with American Edward Kienholz (1927–1994) who started working in this direction in the 1960s was invented separately in the USSR by Irina Nakhova (b. 1955) and Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023). Underground artists who could not display their conceptual works in public spaces and state institutions, constrained by the limits of censorship and fed up by omnipresent propaganda narratives, won their artistic freedom by turning their bedrooms or studios into surreal, otherworldly spaces where fantasy ruled. These immersive artworks existed only for a few days and could be seen only by a small circle of friends. On several occasions Irina Nakhova turned a room in her apartment into a total installation during the mid-1980s – a series which later became known as “Rooms”. Kabakov assembled his now famous installation “A man who flew to outer space from his own room” in his studio in 1982 which was a poignant metaphor for the escape from Soviet reality, possible only in the realm of art. There’s something sincere and selfless about this short-lived medium as most total installations exist only for the duration of an exhibition before they are dismantled. They are difficult to store and nearly impossible to sell (especially if the artist is not a world star like Kabakov or Kienholz whose works are coveted by major museums). Inspite of this, there has been a renewed interest in total installations in Russian art in recent times.

A shelter, a safe place to hide and regain one’s peace of mind has, perhaps unsurprisingly, become a popular theme today. Yet, the boundary between what is a safe hideaway and what is a claustrophobic, suffocating space has become thinner. The tradition started by Kabakov’s ‘Labyrinth. My Mother’s Album’, where the viewer learns about the adversities in his mother’s life through her own handwritten confessions displayed on the walls of semi-dark and narrow passages seems to have endured with new meanings into the present. Irina Korina (b. 1977) who has worked in this genre for many years, literally put up her tent in Moscow’s XL Gallery last Spring. Her installation ‘Melting’, which was on view in March and April of 2023, was a cosy oasis of soft fabrics, old Soviet furniture and mysterious ceramic objects. Some of them depicted piles of melting snow, mushrooms or skis. “Reality is melting around us, yet never melts away completely”, XL’s owner Elena Selina commented sardonically. In this white, nurturing space, one’s mind slipped back into childhood, clinging to old, familiar objects yet at the same time aware that they were losing their shape in strange, unnerving ways. This Spring Eldar Ganeyev (b. 1977), an artist from Krasnodar and former member of ZIP art group erected a plywood structure called ‘Shell’ at Moscow’s Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries. This cramped space filled with Soviet vintage from the 1980s had a similar atmosphere of distorted reality. 1980s music was playing in the background, viewers were invited to play ‘micro–ping pong’ with tiny rackets and a ball on a small table placed in a small box-like room. Yet the walls of the structure were fragile and the cosiness of the space illusionary. Viewers were torn between curiosity and the desire to make a quick escape.

Can one actually live in a total installation? Mikhail Rubankov (b. 1983)’s project questions the border between conceptual art and marketing in an installation he has made for a room in the Marco Polo hotel in Moscow. At a time when Russia’s hospitality industry has been forced to reinvent itself, with the sudden absence of international tourists, it has refocussed its energies on the local market - perhaps the art-ification of hotels has become a budding new trend. Inspired by David Lynch, Rubankov has created an engaging environment filled with mystery and visual puzzles. On the wall in the hotel room you find a mural curiously made in the style of native art of the Northwest Coast of America; in the bathroom you find black-and-white photographs hanging from a rope and a totem-like abstract sculpture made out of an old high-voltage insulator. There’s a vintage Soviet radio sitting on the bedside table. The fascination among young artists for vintage objects from Soviet everyday life seems to have become nothing short of an obsession. Today these artefacts of an empire that has long since disappeared, look like a memento mori. These salvaged relics from the sunken Communist Atlantida remind us that empires do not last forever. For those in Moscow, on 6th July the general public can visit room 304 - just for one day – after which it will remain just for the hotel guests to enjoy, the space can be booked as a normal hotel room.

Artist Anastasia Litvinova (b. 1988) has chosen a more laconic approach in her project ‘Two Homes’, on view in Moscow until 6th of August. She has turned one of the vaulted, windowless halls in the Moscow Museum of Modern Art into a ghostly replica of her own apartment. The space has become a surreal labyrinth, whose walls are formed by light fabrics with cyanotypic prints of her own home. This 19th century technique lends the image a haunting, blueish colour, it is like a negative stripped of unnecessary details. Reality becomes unreal and what was a home becomes a strange, unfamiliar place, a distant memory. At a time when millions of people have been displaced from their homes or have left them out of fear of something bad happening in the future, the artist has captured the overwhelming and tragic feeling of the illusion of safety and stability of home rather than its reality.

Meantime in St. Petersburg, artist Piotr Diakov (b. 1983), a member of the North 7 art group has turned his total installation into a monument to destruction. In his project ‘Protected Zone’ at the Anna Nova gallery his favourite motif of human fingers detached from a body acquires ominous undertones. Wallpapers decorated with fingers cover the walls, and various objects and sculptures populate the rooms, adding to an overall sense of disintegration and decay. There is a pile of broken ceramic volleyballs and a monstrous stuffed animal, half ostrich, half fox, balanced precariously on narrow planks resembling skis. The message behind this recent glut of total installations seems much bleaker than that of the Moscow Conceptualists. Reality is falling apart, and art is not a safe haven anymore.

Mikhail Rubankov

Marco Polo hotel

Moscow, Russia

From July 6 onwards

Anastasia Litvinova. Two Homes

Moscow, Russia

28 June – 6 August, 2023

Piotr Diakov. Protected Zone

St. Petersburg, Russia

15 June – 20 August, 2023