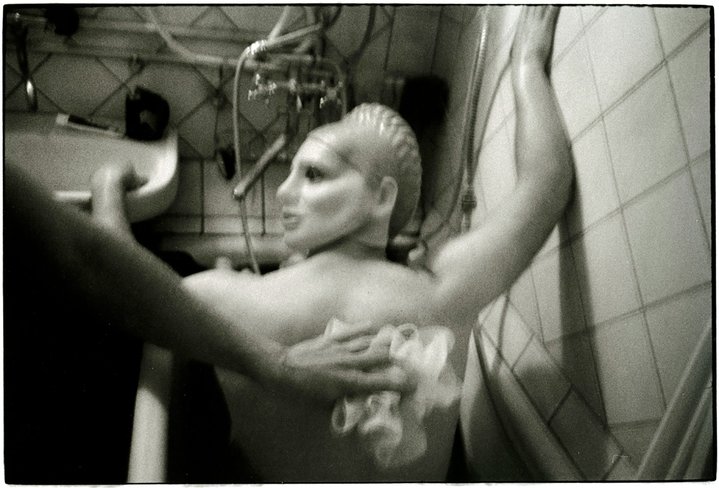

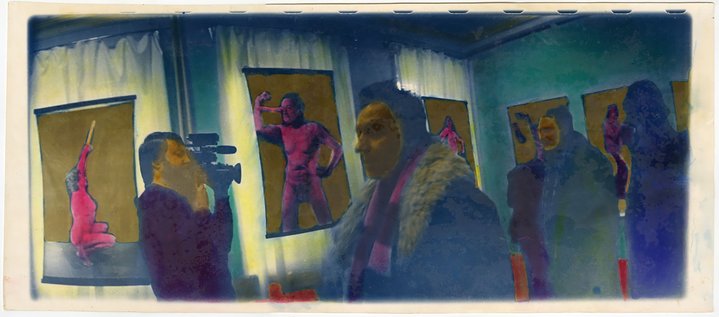

Viktor and Sergiy Kochetov. Horizontomania, 1984. Gelatin silver print colored manually. Courtesy of the artists

Global exposure for Kharkiv's photographers

The Kharkiv School of Photography is getting unprecedented international recognition, after works by members of this influential movement in Ukrainian art were recently acquired by the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

In March 2021, the Ukrainian Club of Contemporary Art Collectors announced that more than 200 works by Ukrainian artists were to be donated to the Centre Pompidou in Paris. This major donation was concluded after several years of thorough research, led by the director of the Centre Pompidou Bernard Blistene and curator Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov; Ukrainian art collector and philanthropist Zenko Aftanaziv together with Russian gallerist and collector Marat Guelman were also both involved in the acquisition. Now, a dedicated exhibition featuring these works in the Centre Pompidou’s permanent collection is in the planning for 2022.

The works which have been donated cover several decades of Ukrainian art from the 1970s to the 2000s and a significant part of the gift are by photographers from Kharkiv, one of Ukraine’s largest cities. Two of the most internationally recognized and popular contemporary Ukrainian artist-photographers, Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938) and Sergey Bratkov (b. 1960), are from Kharkiv. However, the Pompidou donation emphasizes other, lesser-known names, such as Evgeniy Pavlov (b. 1949), Oleg Maliovany (b. 1945), Jurii Rupin (b. 1946), Serhii Solonsky (b.1957) and the ‘Shilo’ group, formed by Sergiy Lebedynskyy (b.1982), Vladyslav Krasnoshchok (b. 1980), Vadym Trykoz (b. 1984).

Due to the Ukraine’s lack of visibility on the international art scene, few specialists know that in addition to Mikhailov and Bratkov (who have already long been represented in major international museum collections including the Centre Pompidou), Kharkiv has boasted several generations of outstanding photographers. They have all worked with similar aesthetics, defined collectively as the Kharkiv School of Photography. In 2019, an exhibition titled ‘The Forbidden Image’ was held by Ukraine’s largest contemporary art museum, the PinchukArtCentre. This show was dedicated not just to Boris Mikhailov, but the wider phenomenon of the Kharkiv School of Photography. It was curated by PinchukArtCentre’s artistic director Bjorn Geldhof together with Martin Kiefer, who is in charge of Contemporary Art at the Musee du Louvre, and Alicia Knock, curator from Contemporary and Research Department at Centre Pompidou. After the exhibition’s success, the international demand for the Kharkiv group of photographers grew significantly.

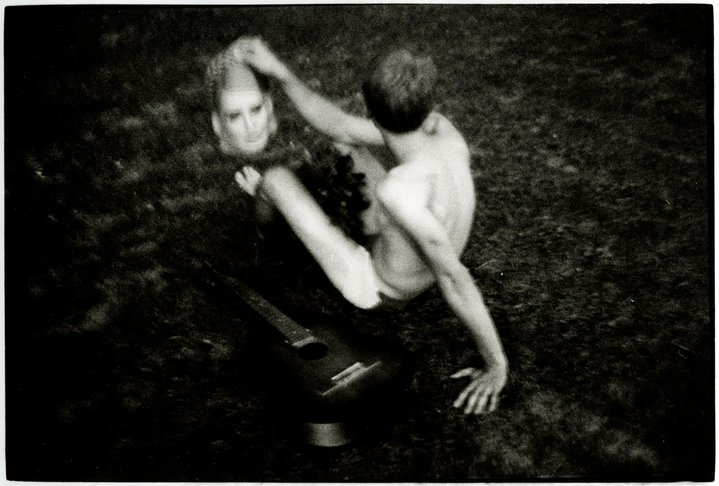

The Kharkiv School of Photography can be used as an umbrella term for several generations of artist-photographers who worked in the city from the late 1960s to the 2010s. Kharkiv was one of the largest industrial, educational and scientific centres, both in the USSR and then, later, in independent Ukraine. It had a vibrant avant-garde tradition, an active underground scene and a school of art with a strong social focus. In Soviet Kharkiv, however, there were high levels of poverty, with penniless students and poets living side by side and the Kharkiv bohemian scene developed in close quarters with those living at the bottom of the social ladder. This impacted the tenor and themes of the art produced by artists from the city.

In this context, at the end of the 1960s, it so happened that a whole host of young artists appeared who did not come from within bohemian circles, but from a local amateur photography club. The first to experiment with a series of conceptual photos was Boris Mikhailov, at the time working as an engineer. Soon, a few other enthusiastic amateurs would join this local photo club. The majority of them worked at one of Kharkiv’s numerous factories. They were not only interested in the technical aspects of the discipline, but also fascinated by the aesthetic and semantic expression that a photograph contained.

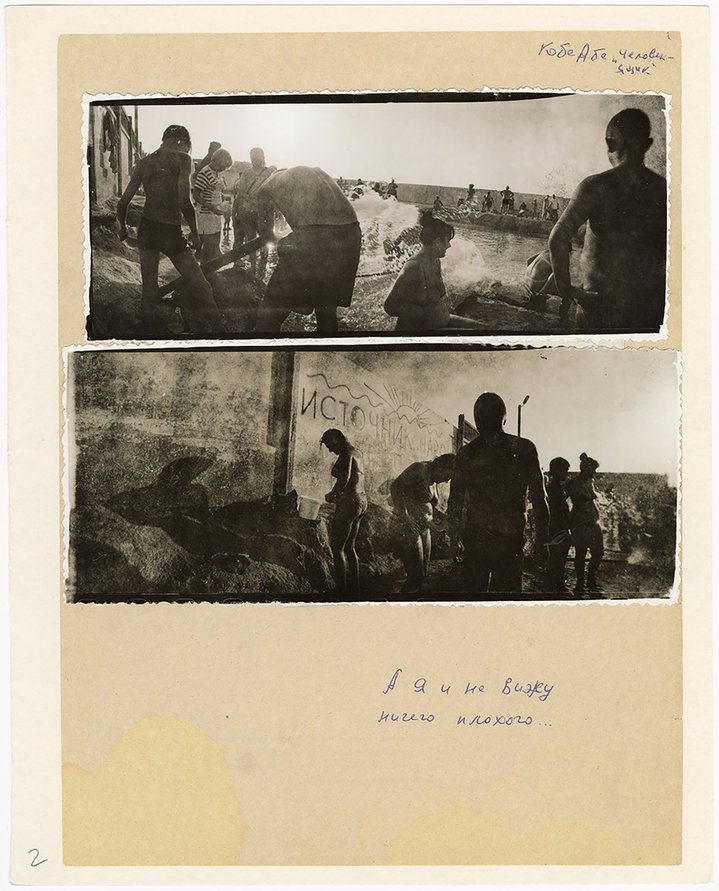

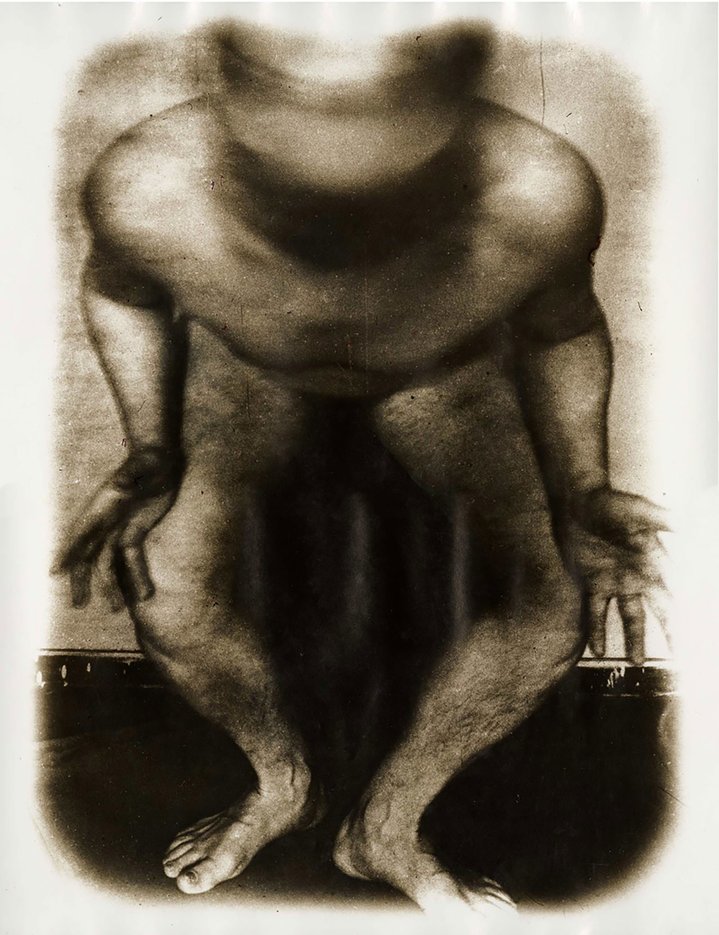

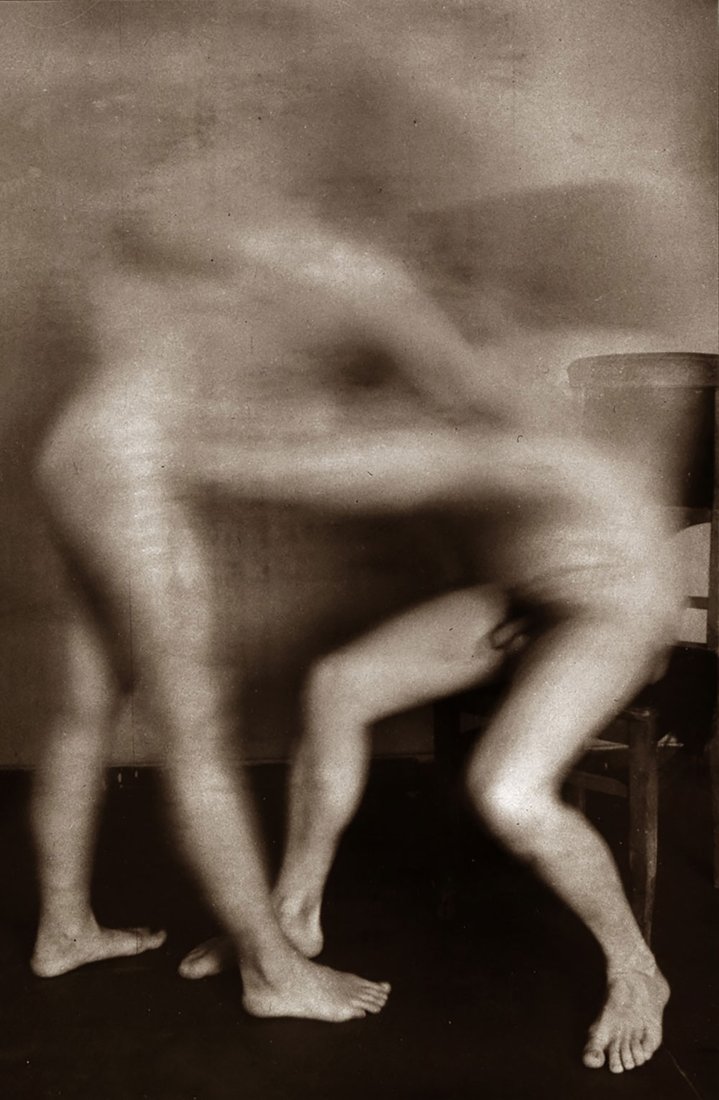

The ‘Vremia’ (“Time”) group was formed in Kharkiv in 1971. Among its most active members were Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938), Yevgeniy Pavlov (b. 1949), Yurii Rupin (b. 1946) and Oleh Maliovany (b. 1945). The photographers developed an artistic method they called the “theory of the blow”. Their photographs were meant to challenge a stagnant Soviet society through form and content. The result was a movement that became known for dragging down Soviet mythology and using shock and brutality in its art. When utopia had ossified and turned into a dismal cargo cult, the artists of this generation attempted to focus on the everyday, on the things that were not covered by the Communist Pravda newspaper. Instead, they preferred to tell the stories that lay beyond official Soviet photography’s field of vision.

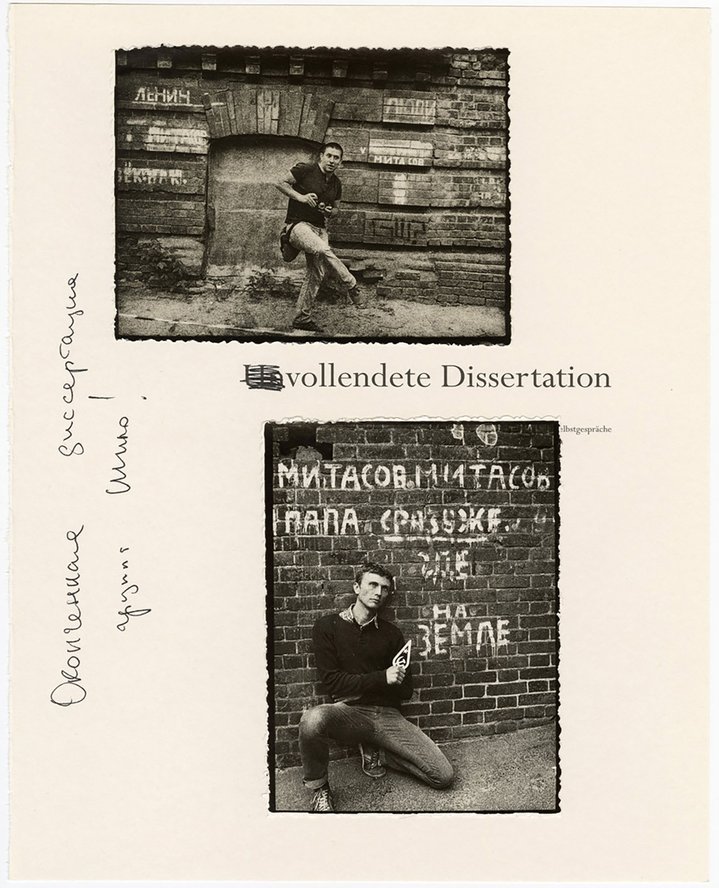

In 1976, due to the radicalism of Vremia’s members, the Kharkiv Regional Photography Club was shut down. However, even though the group no longer existed formally, its photographers continued to attend various exhibitions, using its name until the 1990s. Vremia’s only exhibition in Kharkiv took place in 1983 in the House of Academicians and it was closed on the day of the opening.

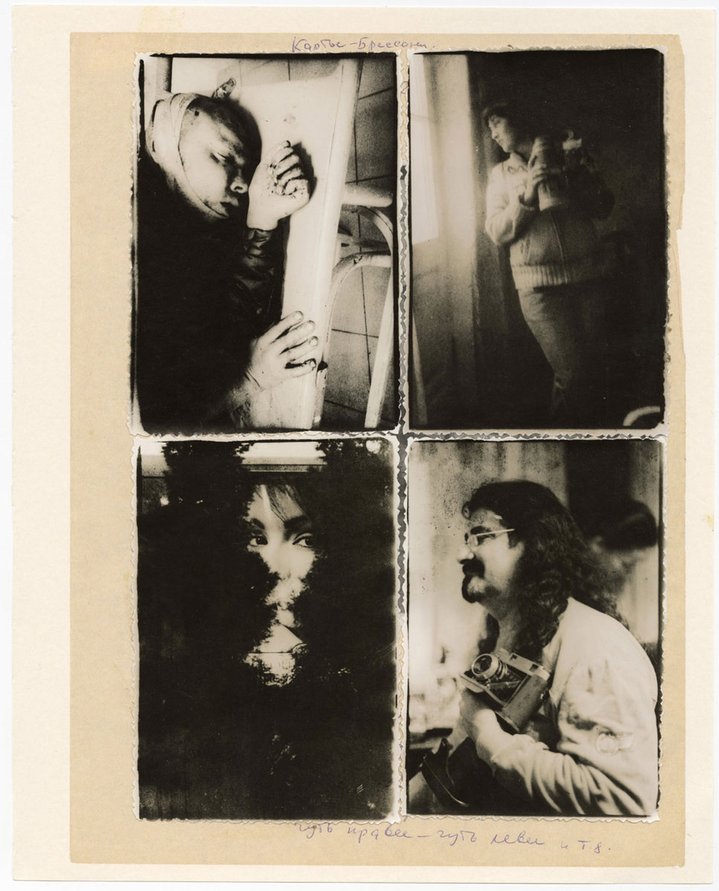

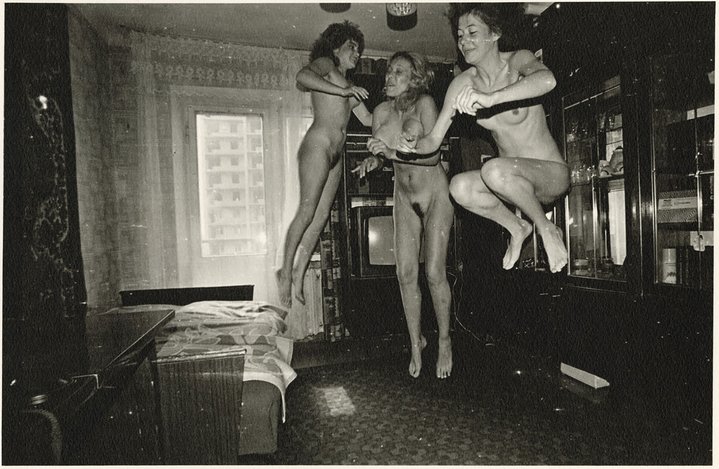

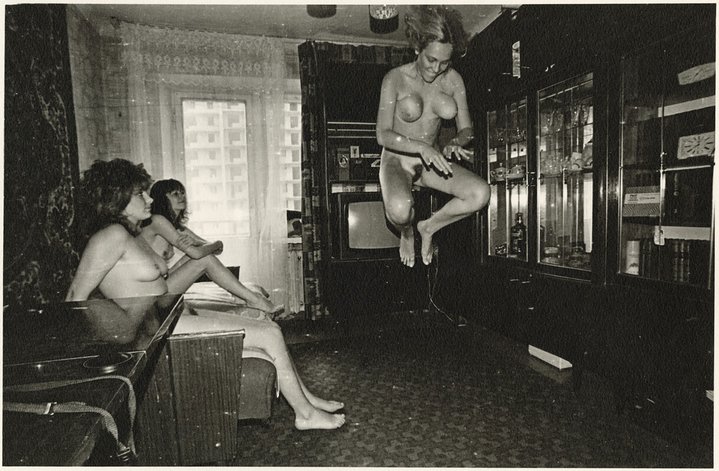

Provocative nudity, the grotesque in everyday life, the general ugliness of the urban and social fabric, especially during the last decades of the USSR, are central subjects and the Kharkiv photographers were absolutely merciless to the reality around them. The most outstanding works of this period were created by Boris Mikhailov, Yevgeniy Pavlov, Yurii Rupin and Oleh Malevany. Photographers worked both in both black and white and colour, although at the time the latter was more expensive. One of the most recognizable techniques typical of this group of artists is hand-coloured photographs. In Soviet times, professional photo studios churned such images out. They were popular, as everyone asked to see old black and white photos of their late relatives in colour.

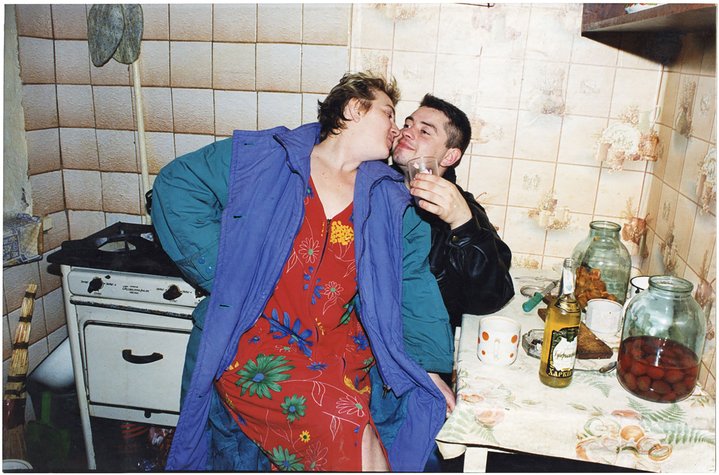

During perestroika, a younger generation of Kharkiv photographers came onto the scene, which included the ‘Gosprom’ (an abbreviation meaning “state industry”) group. It’s members included Sergey (Serhii) Bratkov, Ihor Manko, Hennadii Maslov, Kostia Melnyk, Mykhailo Pedan, Leonid Pesin and Volodymyr Starko. During a surge of interest in all things political during this period, the group focussed its attention on reportage and documentary photography. Among other outstanding photographers of the second wave of Kharkiv photography are Serhii Solonsky, Viktorand Serhiy Kochetov and Roman Pyatkovka.

The third wave of Kharkiv photography was in the late 2000s, when the ‘Shilo’ (Sergiy Lebedynskyy, Vladyslav Krasnoshchok and Vadym Trykoz) group emerged. They were far from the original bohemian circles from which the school took its inspiration. Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, for example, is a practicing surgeon, however, these artists adopted the classical features of the Kharkiv school – social radicalism, hand-coloured photography and black and white analogue aesthetics. In 2018, Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, two members of the group, founded the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography (MOKSOP), the first Ukrainian art institution and collection fully dedicated to the Kharkiv School of Photography and its legacy.

New artists who arrived on the Kharkiv scene from the 1990s onwards have actively collaborated with members of the Vremia group, or at least employed certain points of reference and ways of looking that the group had initially developed back in the 1970s. This close attention paid to passing on the group’s artistic legacy to younger artists and its consequent diffusion into more recent and present artistic practices shows the real contribution of the Kharkiv School of Photography. Thus, it is hoped, the artworks by the Kharkiv School of Photography will not only complement the Centre Pompidou’s vast collection of late Soviet art but will for the first time allow European curators, researchers and exhibition goers to understand the Kharkiv school as a complex and unique phenomenon on the international art map.