From Street Menace to Art Muse: Russia’s Gopnik Renaissance

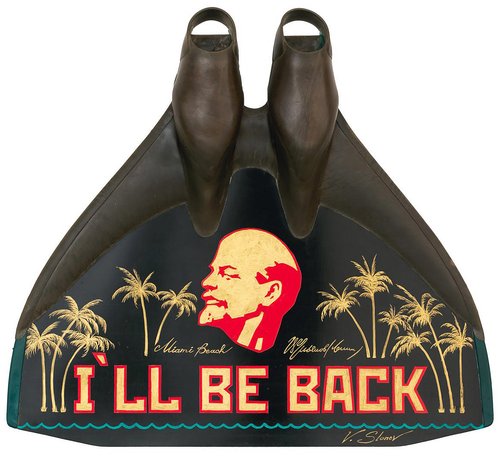

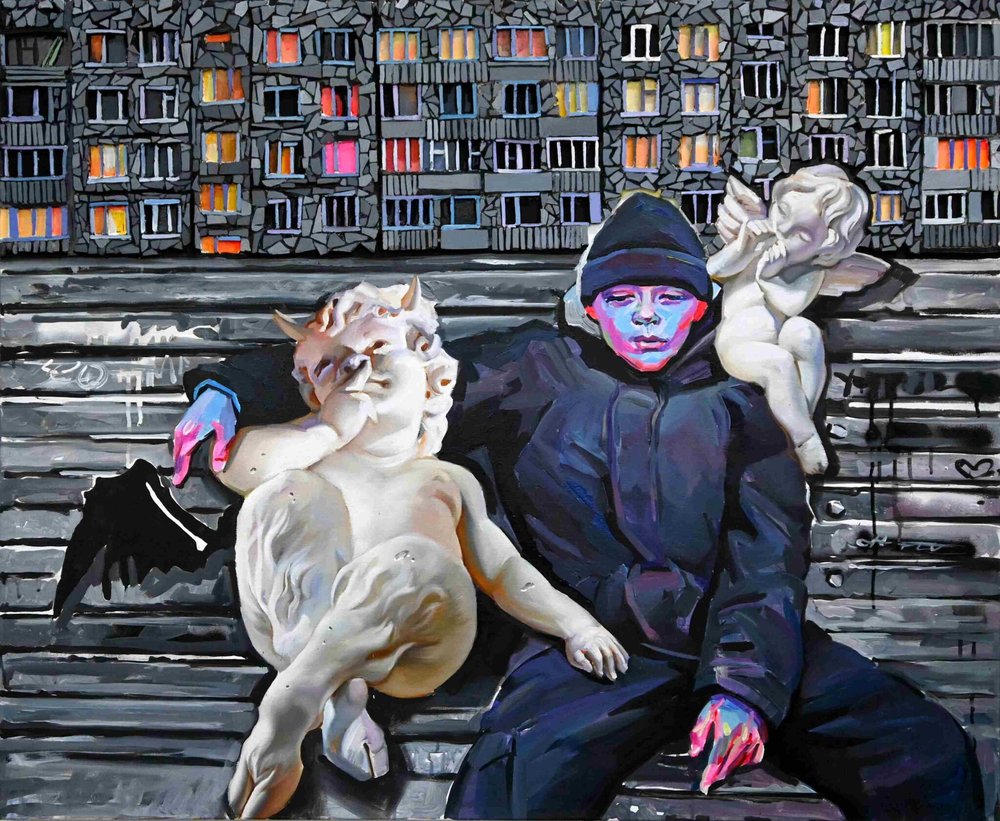

Anna Selina. Panelka (Panel house), 2025. Courtesy of 11.12 Gallery

Once symbols of street crime, gopniks have turned into artistic icons. Once feared, now glamorized or satirized, they populate contemporary exhibitions across post-Soviet states. This shift raises questions: is it nostalgia, critique, or a reflection of evolving social anxieties in contemporary Russia?

There is nothing glamorous about gopniks. They are not even likeable. It is thought that their name comes from gop-stop, slang for street robbery (or from the acronym GOP meaning the City Dormitory for Proletarians, a dormitory for destitute workers in Soviet Leningrad in the 1920s). Unruly working-class teenagers and twentysomethings from the suburbs and small towns, dressed in black Adidas suits, were a staple of the Soviet urban landscape in the 1980s and 1990s. They went around in groups and spent their time squatting in public places, smoking and chewing sunflower seeds, and engaging in petty crime. They became notorious for bullying and beating up members of youth subcultures derived from the West such as hippies and rockers as well as for their racist attitudes and habit of harassing migrants from the Caucasus and Central Asia. Yet, surprisingly, although they have disappeared there is a nostalgia for them in the art and pop culture of the former Soviet countries. ‘Guy’s Word – Blood on the Street’, a series about youth gangs in the city of Kazan in the 1980s, was a huge hit on Russian streaming platforms in 2023 and was broadcast on national television the following year.

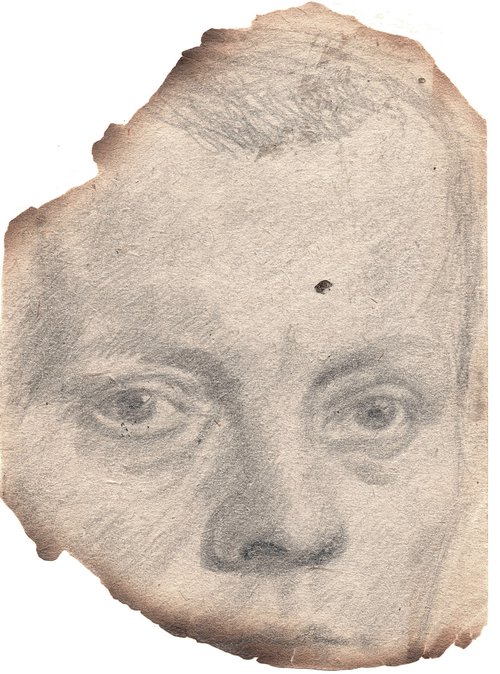

Gopniks, drunks and other fringe elements of Russian society were all important subjects for the late Dmitry Vrubel (1960–2022), famous for his 1990 mural ‘My God, Help Me Survive This Deadly Love’ on the Berlin Wall which depicts a kiss between Brezhnev and Honecker. Towards the end of his career, Vrubel’s interest in gopniks began to verge on the obsessive, "Russia is ninety per cent gopniks," he once said in an interview with Afisha magazine in 2008. In 2010, while living in Berlin as an émigré artist, he scoured Russian social media for the most striking and repulsive images and, with his wife and collaborator Viktoria Timofeeva, he used them to create monumental and unsettling paintings. Talking of gopniks, Vrubel said “they believe every problem can be solved by brute physical force. They divide the world into their own people and strangers.” According to Vrubel, this also applies to the country's political elite. “A gopnik who follows one path remains a gopnik, and one who chooses the other path becomes a politician. That is to say, if a gopnik is well fed, is well dressed, is not allowed to drink too much, goes to spas, then he will become a politician”. Today his words sound like a terrible premonition. His warnings were not heeded in his lifetime. The paintings of gopniks that the artist couple exhibited weekly at PANDA, an independent theatre and cultural centre in Berlin, were not popular with museums or collectors. Vrubel eventually lost interest in the subject. He became fascinated by the possibilities of VR technology and turned to creating virtual exhibitions and museums for himself and independent clients.

Yet younger artists have a more sympathetic view of them, finding them exotic, even exciting rather than fearful. A new exhibition by Anna Selina (b. 1990) at 11.12 Gallery in Moscow offers a far less critical approach to the subject. On her canvases, which sometimes ingeniously combine painting with mosaics, these social outcasts are glamourised and even juxtaposed with classical putti and nudes, as if the guys in black caps were claiming their rightful place in art history. At the top and bottom of the gallery walls, catchy phrases from criminal folklore such as 'A bandit is hard to love, but impossible to forget' are written in tidy, steady handwriting. The palette is mostly black and white, but the faces and bodies of the characters glow with bright pinks and blues, as if illuminated by the coloured lights of a nightclub - or the infernal flames of hell. These images have nothing to do with the real world, they seem to have come straight out of a morbid fantasy or a drug-induced trip, and evoke little emotion from the viewer, only confusion. Who are these people and what do they represent? Unlike Vrubel’s human-shaped monsters, they are not even capable of provocation – they are too glamorous for that.

TOY team, a street artist duo from Nizhny Novgorod who made the fateful transition from city streets to gallery walls about ten years ago created a series of paintings about young gopniks. In 2018, it was shown at two hip, independent Russian art venues – the Smena art centre in Kazan’ and the now-defunct Perelyotny Kabak (The Flying Inn) in Moscow. For TOY, the life of a gopnik is mundane, almost boring. The viewer feels no distance between the artists and their subjects. They come from the same background and share the same bad memories of high school. After all, graffiti artists are often considered hooligans by their neighbours. With their flattened, volume-less figures and close-up, fragmented compositions, the artists move beyond social commentary into the realm of formal experimentation. Ugly reality and high art collide in unexpected, even absurd ways, making these paintings as “impossible to forget”, as the proverbial bandit.

For many artists, the almost extinct gopnik has become a legendary, comic-like figure. Ivan Seryi (b. 1991), another artist from Nizhny Novgorod with a street-art background, has depicted a gopnik as a fantastic creature, a zombie or an alien, creating a three-metre-high squatting figure with distorted features for his 2019 exhibition at Futuro Gallery. The artist believes that in an imaginary post-apocalyptic Russia, the two ruling classes would be gopniks and policemen, as they are stronger than the rest of the population and can adapt more easily to the changing reality. There are many lesser-known artists who have been inspired by this subculture. For example, Andrey Bogatyrev from Ivanovo, who paints in what he calls the “gop style”. Or Muscovite Daniil Kudryashov (b. 2000), whose collage-style paintings are densely populated with gopniks and policemen. His solo show at the Bizon Gallery in Kazan in 2023 was called ‘Patsan and Eternity’. (Gopniks call themselves Patsans or Boys). In this city, notorious for its history of youth gangs, interest in the subject is unwavering. Some would say it borders on pride.

This interest, however, is not local as the gopnik subculture was widespread throughout the Soviet Union and flourished even more after its collapse in the 1990s. Today other post-Soviet countries are not immune. Estonian artist Alexei Gordin (b. 1989) draws inspiration from memories of his childhood in the Russian city of Tomsk when he paints life in the suburbs, populated by cartoonish gopniks. “On the one hand, it was an embarrassing blot, you could say, but now it has become our export,” he says in an interview with Estonian TV channel ERR. “It’s a visual culture that we, as Eastern Europe, are trying to sell before it completely disappears, before we completely dissolve into Western culture.”

It may seem that artists are catering to poor taste by choosing a mildly provocative subject and treating it in a caricature-like manner, without even attempting a deeper analysis of the social phenomenon. Indeed, their works are often shallow and poorly executed - but they do reflect a certain trend. The fascination with Adidas-clad mobsters is obviously a form of nostalgia – but for what? For the lawless days when youth gangs had the streets to themselves? The very idea sounds absurd. So what is it? Could it be that in an era when the monopoly on violence seems to have passed to the government, the gopniks look like the lesser of two evils?