Ernst Neizvestny, the Mutilated Titan

The Epoch of Neizvestny. For the Artist’s Centenary. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Courtesy of State Tretyakov Gallery

State Tretyakov Gallery presents a comprehensive retrospective of the renowned Russian-American sculptor Ernst Neizvestny. Marking one hundred years since his birth, the exhibition offers the first complete biographical survey of the extraordinary career of this fearless artist and Second World War veteran.

It is curious that while Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016) is widely known – one of the few Russian sculptors whose reputation extends far beyond Russia – there has until now never been a major chronological survey exhibition presenting the full scope of his work and career. To mark the centenary of his birth, the State Tretyakov Gallery, with the support of other museums, foundations, and art institutions, as well as Russia’s Channel One television network and its director Konstantin Ernst, has brought together an all-encompassing exhibition entitled The Epoch of Neizvestny. For the Artist’s Centenary.

Curated under the leadership of Elena Gribonosova-Grebneva, a specialist in Soviet and post-Soviet sculpture and researcher at Moscow State University, the project draws on the work of a large and dedicated scholarly team. Together they have created a unique and impressive homage to Neizvestny – one that not only reconstructs the trajectory of his artistic life, but also situates it within the broader historical forces that shaped it. The exhibition’s timing is particularly resonant, coinciding with the eightieth anniversary of Russia’s victory in the Second World War, an event widely commemorated across the country over the past year and one that bears directly on Neizvestny’s own biography as a war veteran.

Ernst Neizvestny was a real superhero – a fearless fighter and uncompromising champion. He survived against all odds after sustaining injuries during the Second World War that should have been fatal. A death notice had already been sent to his family, yet he prevailed in the face of catastrophe and went on to become one of the great monumental sculptors of the twentieth century.

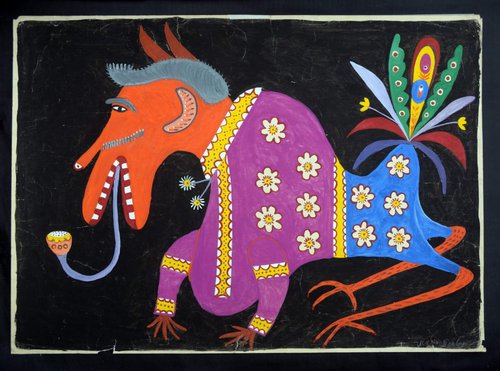

His fearlessness was not confined to the battlefield. During the notorious exhibition ‘Thirty Years of MOSKh’ (the Moscow Union of Artists) at the Manege, Neizvestny entered into a fierce and public confrontation with Nikita Khrushchev, then General Secretary of the Communist Party, over the freedom of art. It was a remarkable moment – and, in a moral sense, Neizvestny won. Khrushchev behaved as a crude apparatchik, lecturing artists on the correct Party view of art and denouncing Neizvestny’s colleagues – among them the metaphysicists and non-objective artists exhibiting at the Manege, including Eliy Belyutin (1925–2012), Boris Zhutovsky (1932–2023), Ülo Sooster (1924–1970) Yuri Sobolev (1928–2002), and Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018) – as “abstractists and perverts.” Neizvestny responded with a heated and fearless rebuke, unhesitatingly defending his peers and asserting the dignity of artistic freedom in the face of power.

That same spirit of resistance defines Neizvestny’s artistic language. His sculptural images are endowed with catastrophic force – not because they depict destruction, but because their heroes are titans who are wounded through and through: bodies twisted, pierced, writhing in pain, yet unmistakably alive. They suffer, but they endure. They resist.

Here it is impossible not to draw a parallel with the tormented forms found in the work of Vadim Sidur, another Second World War veteran who transmuted the trauma of severe injuries into a deeply personal and harrowing artistic vision. In both cases, sculpture becomes not a celebration of power, but a testament to survival – art as an act of defiance against physical destruction, historical violence, and moral collapse.

The exhibition at the Tretyakov is reassured and professional. What stands out as particularly valuable in Russia today is the opening section, called “War is...” with the artist’s own words: “My first works were called ‘War is...’ I perceived war not as a victory parade but as a tragic, contradictory and unnatural phenomenon for humanity. ...Then this grew into ‘Gigantomachy’, then into ‘The Tree of Life’”. Hatred of wars, violence and suffering became a colossal theme for Neizvestny in the creation of a kind of form-making laboratory in which the terrible and the beautiful enter into eternal dispute, unite in whirlwinds, split into atoms, details, corpuscles and are drawn together again under the sign of his beloved Möbius strip, or the infinity sign.

Such poetry found in the union of death and life refers to the cosmogony not only of Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’ (which Ernst Neizvestny illustrated twice) but also to the mythology of the strange English gothic artist, hermit and mystic William Blake (1757–1827). Ernst Neizvestny seemed to transfer the alchemical and mystical themes of the dismemberment and synthesis of life into the realities of the Soviet world. He emerged as a kind of Soviet Frankenstein, anticipating themes important to contemporary culture – those of a technogenic civilisation populated by cyborgs.

From an anti-war theme to ‘The Tree of Life’, the exhibition is laid out down two enfilades, effectively pierced by broken rings, the ensemble designed by Fatali Talybov and Ekaterina Korobchuk. The pivotal theme turns out to be a model of Moscow’s Manege built into the enfilade, where the historical debate between Khrushchev and Neizvestny took place on 1st of December 1962. The curators of the exhibition, together with Channel One, have animated this famous dispute as a virtual video reconstruction, using period photographs and recordings. The dialogue of ghosts looks rather weird, but it unambiguously anticipates the theme of cyborgs. In the Manege “model,” three distinct halls articulate the three principal directions of Soviet official and underground art represented at the exhibition ‘Thirty Years of MOSKh.’. The first is Socialist Realism. The second is modernism with abstraction and sculptures by Neizvestny. The third is the ‘austere style’ of the more democratic wing of MOSKh. Artists representing this strand like Nikolai Andronov (1929–1998), Pavel Nikonov (1930–2025) and Andrei Vasnetsov (1924–2009) put into paint the difficult everyday lives of working Soviet people by using sparse colours. As you pass through the reconstruction of the 1962 Manege exhibition, you can clearly see how much better and more interesting Ernst Neizvestny and his friends were than the official artists represented in the first hall and how much bolder they were than those in the third hall. It is as if we are comparing Soviet films from the 1930s to 70s with Stanley Kubrick's ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’.

The exhibition concludes with sections of monumental works that Neizvestny created after leaving the USSR for America in 1976 and his return to Russia in the 1990s–2000s: ‘Gigantomachy’ and ‘The Tree of Life’.

A simultaneous, panoramic view of Ernst Neizvestny’s work allows us to define his art stylistically and to seek meaningful interlocutors for it within the broader history of world culture. Already in his drawings and engravings of the 1960s, themes derived from the analytical method of Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) are uniquely refracted and fused with the distorted anatomy and weightless corporeality characteristic of the Surrealist vision of Pavel Tchelitchev (1898–1957). The recurring motif of gigantomachy inevitably calls to mind Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) – not as a source of imitation, but as a shared confrontation with myth, violence, and the monumental human form.

One of Neizvestny’s most extraordinary themes is the dissection of organic substance: the body fractured, opened, and unexpectedly transformed into the articulated logic of a metal construction set. At this point, it is natural to recall the post-war modernist sculptors Henry Moore (1898–1986) and Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), and, more broadly, the aesthetics of New Brutalism. As articulated in the writings of the English critic Reyner Banham, post-war New Brutalism has traditionally been associated almost exclusively with architectural practice of the 1950s to 1970s. Its defining features – honesty of materials, the raw texture of concrete and stone, concision, and a lapidary clarity of form – are well established.

Yet when we consider the synthesis of the arts during this period – particularly in the Soviet context, encompassing both the era of the Thaw and the so-called stagnation of the 1970s – it becomes impossible to exclude sculpture from this discourse. The monumental works of Vadim Sidur (1924–1986), Ernst Neizvestny, and Zurab Tsereteli (1934–2024) articulate a shared vision of the age: an epoch of suffering giants, of wounded colossi who once existed in full material presence and yet seem already to be departing – drifting away into a kind of cosmic eternity.

The enfilade of the Ernst Neizvestny exhibition, with its resemblance to the interior of a spacecraft, becomes more than a curatorial device. It offers the viewer the possibility of docking with a world of titans – entering a realm where heroic scale, physical trauma, and metaphysical aspiration coexist in a single, monumental language.

The Epoch of Neizvestny. For the Artist’s Centenary

Moscow, Russia

16 December 2025 – 12 May 2026