Cycles of Revival, Continuity and Repetition

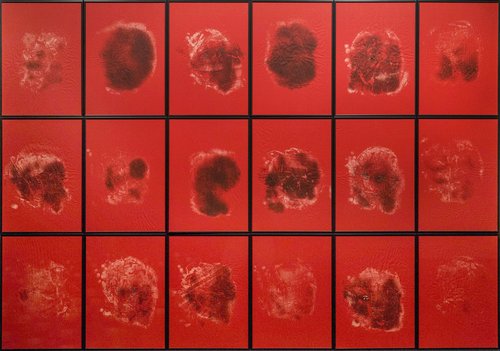

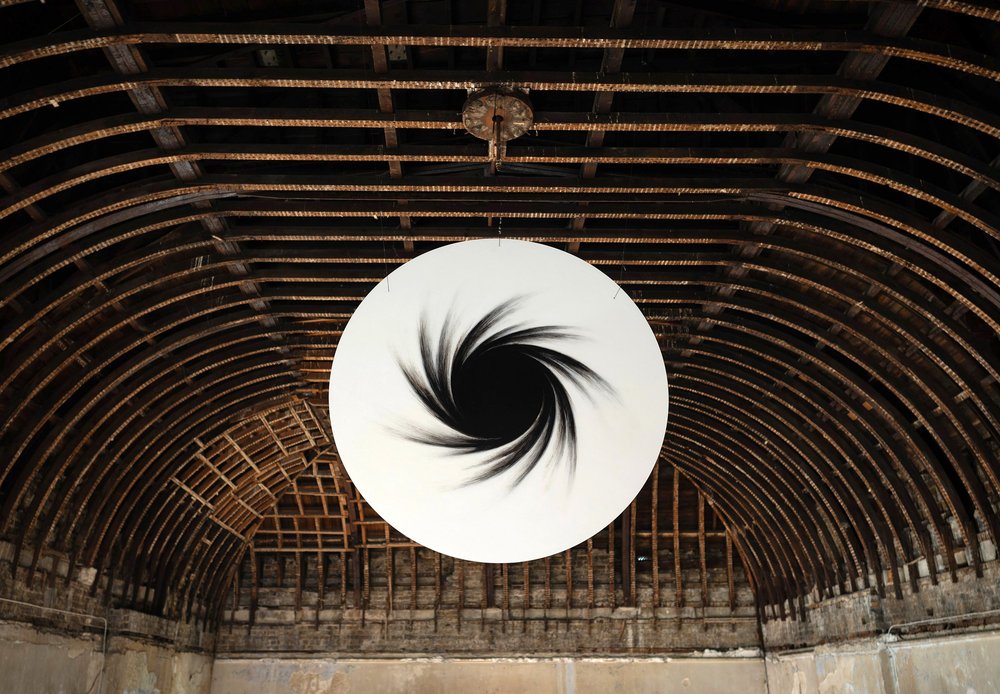

Pavel Otdelnov. Abyss, 2024. Courtesy of the artist

Memory is not just a recollection of the past, it is a dynamic force which shapes our understanding of time and identity. From Pavel Otdelnov’s Soviet-era reflections to Doris Salcedo’s haunting installations, artists reveal the ghosts of history, illuminating how past experiences continue to reverberate in the present. In their hands, memory becomes both a portal and a battleground, constantly reshaped and reimagined.

The mechanisms governing the return of the past remain a mystery to our understanding. Yet contemporary artists have consistently ventured into memory as a distinct aesthetic realm. Within the environments they cultivate, diverse temporal strata intersect and converge, operating under a higher temporal logic where the living and the dead, according to their spiritual state, move freely. These explorations serve as portals into the unofficial history of the 20th century.

In his deep engagement with the aesthetics of time, Pavel Otdelnov (b. 1979) suggests that “a critical stance toward the past helps us resist the nostalgia we inevitably succumb to when reflecting on memories and childhood.” His solo exhibition, ‘A Child in Time’ at London’s A.P.T. Gallery (which runs for four days this month) navigates the landscape of personal memory, a theme that has long captivated him. He also draws upon citation, reclaiming the spoken and the forgotten, collective experiences that shaped generational consciousness within Soviet society.

A central element in Otdelnov’s recent work features a figure which appears to move forwards toward the viewer, which he has borrowed from the opening sequence of ‘Before 16 and Older’, a tv-show aimed at teenagers in the 1980s and 90s. “This sequence still fills me with a sense of awe,” the artist reveals, “as if someone is rushing from the future to deliver a message.” Another marker of a Soviet childhood appears in the form of an elephant against a yellow background from ‘Good Night, Little Ones!’ For millions of children, this image signalled the end of the day, followed by a starlit curtain sequence, the threshold between childhood and adulthood. Then came the ‘Vremya’ news presenters set against their familiar blue backdrop, their greeting – “Dobry vecher, zdravstvujte, tovarischi” [Good evening, hello, comrades] – solidly etched in Soviet collective memory.

Working on unprimed canvas, Otdelnov allows paint to seep and spread, resulting in a soft, luminous effect. “That glow from the TV screen felt like History itself, the very embodiment of Time,” he says. A different, more unsettling luminescence emanates from another of his subjects, Anatoly Kashpirovsky, whose demonic gaze is rendered in a haunting large format. This pseudo-scientist and psychic, who claimed to heal viewers through their TV sets, achieved near-mythical status, particularly following a Moscow-Kyiv teleconference in 1988 where he allegedly assisted in surgery without anesthesia through suggestive techniques. “At that time, everyone sought a sense of security amid the country’s upheaval, attempting to reduce tension. It is natural that people are clutching at anything they can to prepare for the future,” the artist reflects.

In the last section of ‘A Child in Time’, Otdelnov turns to the Primer, the first textbook for Soviet schoolchildren that also functioned as a gateway to official ideology. Communist values were designed to enter the consciousness of a child as naturally as language or the changing seasons. ‘You will learn to read and write’, it promised its young readers, ‘and for the first time, you will write the words most dear and close to all of us: Mama, Motherland, Lenin’. Otdelnov appropriates the familiar Primer’s grid structure, populating it with the anxieties that haunted his own childhood, words that could never have appeared in the textbook: ’radiation,’ ‘war,’ ‘shelter,’ ‘zombies.’

“I no longer want to speak about my personal experiences as an individual but instead focus on what it is that I share with others,” Otdelnov says. “People from the post-Soviet space have reached a crucial moment for reflecting on their experiences. Later, there may not be another opportunity, we will find ourselves in another life, another reality, as always, building something new again.” In talking about memories, Otdelnov speaks less of the past than about the future of that past. Considering this approach to time, a personal revelation takes hold, echoing the sentiment found in Friedrich Schiller: “It is not enough that something shall beginwhich as yet was not; previously something must end which had begun.”

The concept of memory as a dynamic, anti-entropic force manifests in the work of Hrair Sarkissian (b. 1973), a Syrian artist of Armenian descent now based in London. Exploring the architecture of violence, he recreates past locales and moments within a contemporary frame, a therapeutic process aimed at addressing both personal and collective traumas. In his work ‘Homesick’, Sarkissian constructs a two-metre concrete model of his home in Damascus, which he left behind in 2008, only to destroy it during a seven-hour performance with a sledgehammer. Through this act, he simultaneously enacts and attempts to ward off the potential tragedy threatening his parents, who continue to reside in the actual house amidst civil war.

Sarkissian’s personal story is interwoven with displacement, his grandparents having fled the Sasun region, a historical area of Armenian settlements in modern-day Turkey during the Genocide. Driven by a need to reclaim a memory, the ‘Sweet and Sour’ project takes him on a pilgrimage to his ancestral village of Khatsorig which is now a desolate space, a legend stripped of action. The resulting three-channel video installation juxtaposes panoramic landscapes with footage of the artist’s journey of discovery and his father’s emotional response to seeing for the first time the land his family once called home. “[My aim is to] wake up the viewer because we keep repeating the same horrific actions we did 100 or 200 years ago,” says Sarkissian articulating his artistic intention.

Anna Jermolaewa (b. 1970), left her native Leningrad in 1989 settling in the West and over three and a half decades has continued to maintain her self-identification as a “Russian artist living abroad,” negotiating relationships with the past through acts of reconstruction. At the 60th Venice Biennale, representing Austria, Jermolaewa showed ‘Research for Sleeping Positions’, a video work that revisits Vienna’s Westbahnhof station, where she and her husband spent their first nights as newly arrived emigrants. Beside the Austrian pavilion, Jermolaewa installed six telephone booths which were the same as the ones which once stood in the Traiskirchen refugee camp which was her first ‘home’ in the West. These ‘memory boxes,’ from which refugees once rang relatives and left behind drawings and notes on their walls, serve to direct public attention toward migration and the various individual lives caught up in its currents.

Through the excavation of suppressed or erased narratives, Colombian artist Doris Salcedo (b. 1958) engages in a critical interrogation of absence. Her art gives voice to the victims of La Violencia, a decade of civil conflict that claimed the life of one in every fifty Colombians and speaks of what followed: political chaos, drug trafficking, and forced displacement. In the early 1990s, Salcedo began creating installations out of everyday furniture as material testimonies which outlived their owners and functioning as memento mori. Placed within an artificial context, these objects become tools for understanding with sociopolitical significance; close examination reveals the metaphysical essence of all things: the notion of forgetting. Salcedo often fuses disparate chairs, cabinets, and beds together or immobilizes them with cement, monumentalizing them, stripping away their utilitarian functions to transform them into vessels of trauma. In her installation ‘Uprooted’, awarded the 2023 Sharjah Biennial Prize, she assembled a forest of 804 dead trees from Colombia to form the outline of a hut and one that no one can enter. “It is the proximity, the latency of violence that interests me,” Salcedo states. “We are drawn to things that have escaped destruction.” It is through this process of transforming objects and elevating individual narratives that she effectuates cultural memory.

Millennial artist Mohammed Sani (b. 1984), who studied at the College of Fine Arts in Baghdad before relocating first to Sweden and then the UK, approaches memory through intensive observation of his surroundings, a material reality where objects become simulacra of the past. A streak of light under a door, clothes hanging in a wardrobe, the shadow of a vase on a table, all these ordinary moments carry connections to Sani’s lived experiences, surfacing unexpectedly, much like Proust’s Marcel, who truly felt his grandmother’s death (described in the third volume of ‘In Search of Lost Time’) only in the fourth volume, a year after her funeral, when the simple act of untying his boots suddenly conjured her “tender, preoccupied, dejected” face as it had been during their last encounter. Through his paintings, Sani contemplates war and loss, offering fresh perspectives on the nature of conflicts and their aftermaths through a system of mediated signification. These signs simultaneously direct the artist inward and memory becomes a mechanism of alienation that reveals the instability and injustices inherent in our world.

“We all move, one after the other, along the same roads … my rational mind is nonetheless unable to lay the ghosts of repetition that haunt me with ever greater frequency,” W.G. Sebald wrote in ‘The Rings of Saturn’, his profound meditation on the elusive nature of memory. By turning to personal experiences, by examining the brutalities of war or political violence, by unearthing symbols common to entire generations, or by considering these themes through individual stories, we might attempt to reclaim memories, a mission doomed to repetition, over and over again, perhaps with the ultimate result of total failure, acknowledging that the totality of experience can never be fully captured or contained.