Biennale in Georgia

Architecture is not enough: the saga of a Tbilisi bedroom community

Gldani, a Soviet-era micro-district on the northern edge of Tbilisi, is about as far removed from the city’s ancient charm as one can get without leaving its limits. Our taxi driver described it as follows: “You ever been to the middle of nowhere? Gldani is at the end.” In Soviet times, the neighborhood was best-known for housing Georgia’s KGB’s head- quarters. The building has since been renamed the “Georgian Transport Federation. “

And yet Gldani is a community of almost 300,000, according to the most recent estimates, making up nearly a third of Tbilisi’s population. As in any remote bedroom community of Soviet vintage, its residents have developed a plethora of tricks to make the space their own. This goes from building garages to provide the storage missing from the standardised housing of the 1970s, to transforming kitchens into dens and balconies into bedrooms by using spare concrete blocks. This unsanctioned doit-yourself ethos inspired the first Tbilisi Architecture Biennale’s slogan, “Buildings Are Not Enough.”

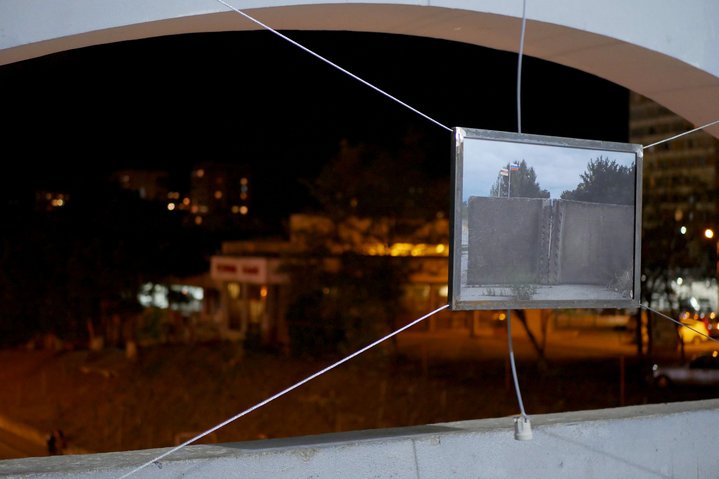

The Biennale’s programme engaged this question on all fronts, ranging from panel discussions to using art installations. One such installation, Maria Kremer’s cozy wooden nook, is built into the footbridge that served as the Biennale’s outdoor exhibition space. It exemplifies the community’s role in giving a structure meaning.

Initially, she aimed to create a living unit within the bridge, turning a public and architectural location into a habitable place. “It was meant to be used by other people,” she explained, noting that local children in particular – who were initially scared to enter the Bridge Habitat – eventually made it “their local gathering space.” Kremer, who is based in Moscow and works in the Russian architect Alexander Brodsky’s studio, called her Bridge Habitat “a dialogue between Gldani and me,” and considers all of her conversations with locals an extension of that project. This dialogue, however, is a rare one, especially in a neighbourhood known even among locals for its marginalised status.

Polish-born Kuba Snopek, a participant in the Biennale’s “Post-Soviet Transformations” symposium, sees the key to such a neighborhood’s longevity in the recognition of its own value from within. An expert in former Soviet cities with a diploma from Moscow’s Strelka Institute, Snopek rejects the idea of “artists coming to a neighborhood and determining that it is cool.”

He believes instead that “good artists find patterns” where others miss them, seeing value in landscapes that seem devoid of content. His chief example are the Moscow Conceptualists, who found inspiration for their groundbreaking contemporary art in the equally revolutionary architecture of Moscow’s own micro-districts, such as the Russian capital’s district of Belyayevo, which Snopek believes should be included in the UNESCO register of historic sites.

He pointed to one of the Tbilisi Biennale’s signature objects, Block 76, as evidence. The nine-storey Soviet-vintage apartment block was turned into a participatory art object in which the building’s residents opened the doors of their ostensibly identical apartments to both guests and artists, showing off the variety possible within this strict framework. Snopek explained: “Here you have 20 identical apartments, but they are appropriated and domesticated in 20 different ways, 20 repetitions, 20 variations. They’re spatially repetitive, but everything else is unique.”

The space for life often determines the frame of mind. So what opportunities can such a restrictive format of living offer? Dima Isaiev and Maria Semenenko, part of the Ukrainian MistoDiya collective, focused on what can be done in such conditions. They made a documentary film in Gldani, walking around for four days and interviewing any local resident willing to speak with them. What they noticed most was “a simple lack of the square footage necessary to support life.”

But there was also a creative effort of no lesser magnitude than what the Moscow Conceptualist artists had achieved. One of their interviewees is a local man who turned his simple garage into a three-storey palace, adding a living room, terrace, and wine cellar to his parking space and creating an intensely personal environment in the anonymous, “top-down” structure of Soviet planned neighborhoods. And he’s not alone. Gldani’s residents, out of love for their neighborhood, have taken it upon themselves to build, legally or otherwise, the structures necessary for what they perceive as the ideal way of life.

In short, the Biennale’s thesis that “buildings are not enough” is not a complaint, but a rallying cry. Rather than relying on top-down urban planning and architecture to meet the incredible depth and variety of human experiences and needs, neighborhoods like Gldani, which are often immediately forgotten by their urban designers as soon as the projects are built, work together to improvise and adapt. What the Tbilisi Architecture Biennale showed is that such a bottom-up participatory model is equally applicable to art, creating a radically local aesthetic in what was once a closed neighborhood. This kinds of collaborations involving both artists and representatives of the public sector, are the key to bringing marginal spaces like Tbilisi’s Gldani into a well-deserved limelight in the post-Soviet world.