Betwixt Cult and Culture: Religion in Contemporary Russian Art

Vladimir Yakovlev. A man with a cross, 1969. Ars Sacra Nova. Religion and symbols in the art of the 1960s. Moscow, 2023. Courtesy of Vellum Gallery

Vellum Gallery in Moscow has curated an exhibition dedicated to religious themes in Russian art of the 1960s. Yet, beyond the limits of what is a small scale show, there is much food for thought says art critic and curator Sergey Khachaturov.

The search for God in the unofficial circle of artists in the USSR was rather half-baked and naïve. In the unofficial art scene from the 1960s to the 1980s most artists had only vague ideas about religion, the texts of the Church and its dogmas. Today it is easy to forget that they were children of the Soviet state. Their ecstatic hankerings after the sacred came together with a fetishization of anything mysterious, mystical, esoteric: everything that was in opposition to what they saw as dead-end Soviet ideology. The teachings of Helena Blavatsky and the cult of Russian Cosmism and the Avant-Garde also played a big role where artists saw revelations of spiritual power no less intense than those emanating from ancient Russian icons.

This secular, even bohemian, fashionable religiosity formed the consciousness of artists who were honest with themselves but lacked education in matters of religion. This path is somewhat analogous to what is the Russian version of Postmodernism, represented by such coryphaei as Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–1986), Dmitry Zhilinsky (1927–2015), Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016) and Oscar Rabin (1928–2018) among many others. Their imagery is full of allusions, reminiscences, and quotations, which turn us not to sarcasm, irony or deconstruction, but to higher meanings of culture, which collect both the spiritual and the mental, the cult and the culture. In his films Tarkovsky shows devotional images of the 15th century Russian icon painter Andrei Rublev alongside paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. For Zhilinsky, the Old Master paintings of the Proto-Renaissance and High Renaissance have a sacral significance offering real prayerful intercession with God. You find images of folk piety and the Perm wooden sculpture of Christ in Prison in Oscar Rabin's frozen landscapes of Lianozovo.

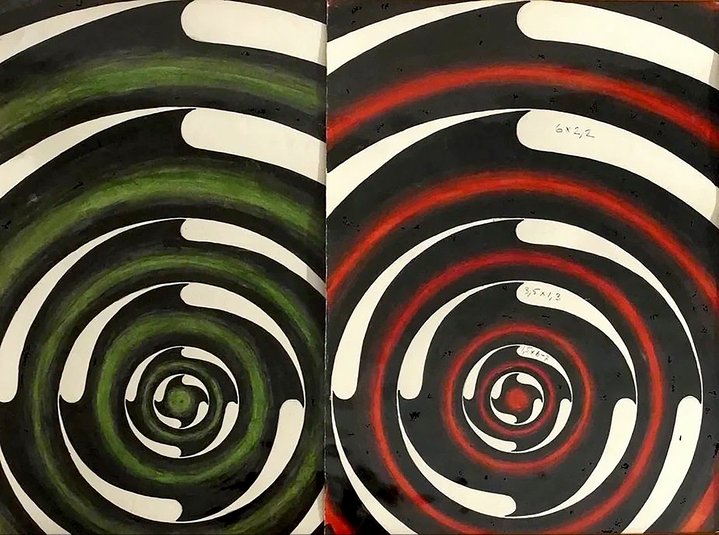

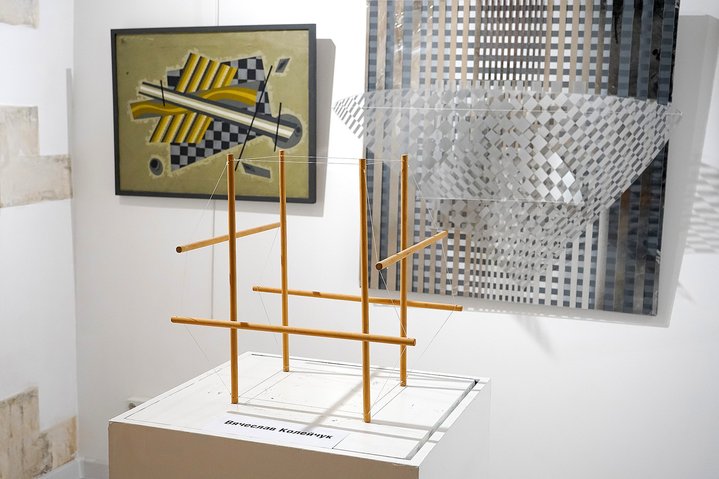

Many artists such as the Kineticists and Op-artists – notably Francisco Infante-Arana, (b. 1943) and Nonna Goryunova, (b. 1944) sacralise the suprematist art of Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) and install it as if it were altars in nature-related Druid cults.

I believe that today this weakened semantic field of ideas about what culture is, and what cult is, does not foster our emotions and provokes irritation. The tragic fate of Rublev's Trinity icon, recently moved from the museum (the State Tretyakov Gallery) to the cathedral (Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow) by the order of the Russian Ministry of Culture despite fierce opposition of experts and restorers, is largely a consequence of this post-Soviet, lax psychology of the museum and fetish of the antique (which applies equally to the theatre and conservatory music). Brought up on this shifting scale of values when art was declared to be the domain of the sacred, and a museum was a temple, it seems today’s politicians chose a victim for the public performance of a cult not among the Russian Orthodox Church sacred relics, the miraculous icons revered among the faithful. They made an attack precisely on the museum where Rublev's Trinity is housed, an icon which has always been associated with cultural, not cultic, assets. It has been physicallyrestored many times. It was only put on public display for people to view in the 20th century. It is not miraculous. However, in the mind of a fanatic of secular spirituality it is comparable to something like Pushkin or the Tsar Bell in the Kremlin. It is as if it is "our everything" and with it we shall win!

That this has happened at all points to a lingering ignorance of the Russian intelligentsia - which includes the art intelligentsia. They have not yet learned to separate the secular from the canonically religious, the sacred from the museum exhibit and culture from the cult. The entire logical development of Russian history with the aberrations of religious themes in unofficial art has, sadly, yet understandably led to this disappointing scenario.

The approach towards metaphysical themes by more conceptual artists of the era was more complex and in a deeper sense more truthful. Religion is the Word. The original, the irreplaceable, the true one. Artists working with the word - the conceptualists - in my opinion, were able to speak more convincingly about the complex, often dramatic, conflicting interactions between the sacred and the profane, the cultic and the cultural.

The Collective Actions’ ‘trips out of town’, Ilya Kabakov’s (1933–2023) installations with little white men or flying angels, already introduce a different modus operandi with regard to sacred matters. They did not fall prey to a kind of home-grown mysticism in order to saturate their creations with borrowed religious images and energies. They honestly diagnosed themselves inside the problem itself. Text is saved by the Context. The Moscow conceptualists established thecontext of the Soviet man's perception of God. It is a context in which one is in a confused state and thus there can be no dogmatic answers about the sacred. The almost druidic cults of these Collective Acts always end not with a miracle but with three dots. Everyone is free to interpret these ritualised performances in their own way. And if it is appropriate to speak of piety for the sacred, then it is through what in the Middle Ages was called ‘scholarly ignorance’, or apophatic theology, theology by default.

In a similar vein of interpretation and meanings, Ilya Kabakov lets angels reminiscent of figurines from children's construction kits into his squalid communal life. The context of interpretation is always broad: where is the line between popular piety and the sentimental mainstream in the spirit of the Camp?

A filter of verbal commentary helps an artist like Yevgeny Gor (b. 1950) to avoid the vulgarity of talking about the spiritual. His metageography of everyday locations requires an intellectual comparison to ancient Tarot cards, to ancient emblems from the Kabbalah. Then the banal signs of the everyday can be understood as fragments or traces of great texts. Only now without violence and hysteria. They could be understood as - or remain - just ordinary road signs, household appliances or footprints in the street... The freedom to choose words is important.

Yevgeny Gor's adopted son, Andrei Kuzkin (b. 1979) brillantly puts into action the strategy of conceptual projection and commentary. He creates his Odyssey in search of the metaphysical core of life. But he never teaches or preaches. Similar in strategy to the ‘Collective Action’ group, the idea of wandering towards essential meaning touches on his own personal history, the history of his family, where he suffers every detail rather than borrows from a collection of relics and miraculous objects. A special theme in Andrei Kuzkin's work is the little man made of bread pulp that Russian prisoners use as the material for their own prison art. Kuzkin creates multi-storey buildings populated with such people. In each cell they cry, pray, mourn, reflect... The installations look like altar compositions with mourners. However, this is not a direct parallel. Again Text and Context expand the space of interpretation as widely as possible. These figures are certainly not of angelic origin. Perhaps they are the everyday mental grimaces of the inhabitants of mass-produced residential blocks? Or maybe they mourn for the higher meanings of a humanity that has lost its faith in everything?

A whole new generation of artists who draw on images and symbols from the catalogue of sacred emblems are Zoomers, belonging to so-called intermedial art. They create hybrid installations with paintings, ceramics and architecture. They create strange and disturbing situations in which unrecognisable objects live their own autonomous lives, indifferent to human life. As admirers of the object-oriented philosophy of thinkers like Graham Harman or Quentin Meillassoux the new generation eschews the unambiguous semantic, emotional appreciation of their work and what seems too human a logic to read them...For adherents of aggregate art like Anya Tagantseva-Kobzeva (b. 1990), Slava Nesterov (b. 1989) and Pavel Polshchikov (b. 1998) it is fundamental to engage the viewer in the unknown, the incomprehensible, which does not fit into any conventions, including those of culture and cult. In my opinion, this kind of art is capable of clearing the mind and the optics, freeing oneself from dogmas and moving towards the new.

Ars Sacra Nova. Religion and symbols in the art of the 1960s

Moscow, Russia

31 May – 17 September, 2023