At Russia’s centre, an art scene is growing

The city of Krasnoyarsk in the heart of Siberia has developed a vigorous artistic community, grouped around the city’s former Lenin Museum, now a contemporary art centre with big ambitions.

One thing that Krasnoyarsk natives love to tell visitors is that, while Moscow may be Russia’s financial and political capital, Krasnoyarsk, a Siberian city of just over a million residents, is its geographic centre. But the lessons don’t end there.

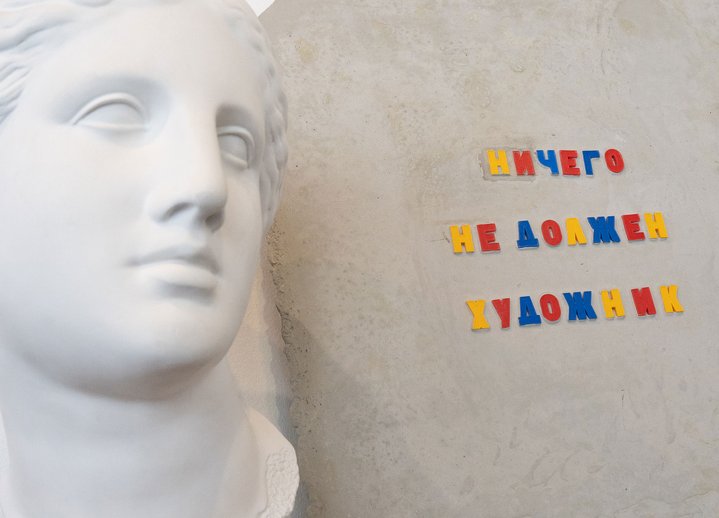

Since the early 1990s, Krasnoyarsk has been nurturing its own practice of artistic experimentation. Due to a dearth of collectors and galleries, a contingent of young creatives has been stepping in to establish alternative platforms for the sale, display and discourse of art. While the city’s Art Academy and Union of Artists have long promoted an understanding of art based on technical skills, some artists like Vasily Slonov (b. 1969) are now pursuing a tradition called “Siberian ironic conceptualism”, a term coined by the Blue Noses Group of Novosibirsk to describe their approach to public art and performance. Others, such as Aleksandr Surikov (b. 1971), relocated to Krasnoyarsk from Irkutsk and developed a practice of visual poetry. Still others have been drawn to Moscow, like Aleksei Martins (b. 1989), who creates seemingly pixelated zoomorphic sculptures. Martins studied painting in Krasnoyarsk and was shortlisted for the Kandinsky Prize’s ‘Young Artist’ award in 2015.

The nucleus of Krasnoyarsk’s cultural life is Ploshchad Mira, a contemporary art museum at the heart of the city. When the cavernous, 5,000 sq. metre space opened in 1987, it was fated to be the Soviet Union’s 13th and last Lenin Museum. “It was the country’s first truly interactive museum”, said Sergei Kovalevsky, Ploshchad Mira’s art director. The building’s architects drew inspiration from Constructivist experiments in the cinematic arts to help visitors “discover” the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“We decided very early not to erase the prior layers of the building. There was a suggestion to change it into a ‘White Cube’, but we stopped ourselves in time,” said Kovalevsky, a trained architect who joined the museum staff when its focus on Lenin was dropped in 1993. Today, Ploshchad Mira thrives in the crosshairs of history. It tries to balance its programming between the original installations dedicated to the Soviet myths of Revolution, as well as new art committed to questioning those very same narratives.

The museum’s most significant move was to launch Russia’s first Art Biennale, aptly called ‘Krasnoyarsk Museum Biennale’. This year’s will be the 14th such event.

If the city’s the Art Academy initially draws youth from across Siberia to study, it is the museum’s magnetic pull that keeps them there. Sasha Zakirov (b. 1989) moved to Krasnoyarsk from the Altai region to study printmaking, but recently left his studies to work in that very museum. One aspect that Zakirov particularly appreciates is the museum’s self-reflexive approach to its Soviet past. “It is wonderful that they didn’t try to suppress history and instead made it into a powerful discursive instrument because whenever you try to hide something, eventually it’s going to crawl out,” he told Russian Art Focus.

Krasnoyarsk is, evidently, a better place to make art than to sell it. “I know about one and a half individuals who can buy things here,” said Kovalevsky. “That’s not enough to build an art market.” Oksana Budulak, a critic and curator at Ploshchad Mira, explained that as a result, locals have to “dig into themselves”. However, Krasnoyarsk’s art world is not giving up. Budulak is organizing workshops about public art in the coming two years, as well trips to Germany and Georgia. The city’s new ‘Yadro’ residency at the former KVANT factory offers space for ambitious practitioners.

The Ploshchad Mira Museum is exploring new programming with Norilsk, an industrial city above the Arctic Circle whose pollution scandals have recently hit headlines. The young museum worker Zakirov broadcasts auctions on Instagram, but almost all the buyers are out-of-towners while sellers “do it more for the publicity than the money”.