Antiquity Unfinished

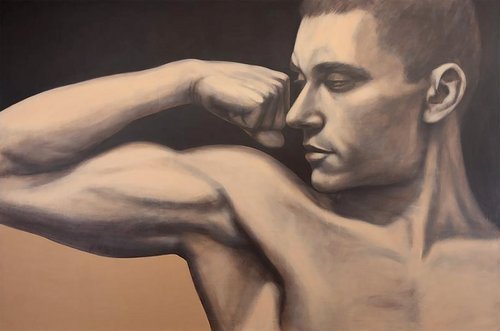

Andrei Mitenyov. Operation. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Photo by Tanya Sushenkova. Courtesy of the Press Service of Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

Ancient myths remain a powerful force in contemporary culture, shaping artistic and ideological debates. In times of chaos and uncertainty, numerous Russian artists from Olga Tobreluts to Andrei Mitenyov are turning to the ideals of eternal beauty and reason, if sometimes just to turn them inside out. From neoclassical revivals to subversive deconstructions, these timeless stories continue to inspire and provoke.

Stories from ancient myth are rightly considered eternal. The reason for this is the high frequency of their use in culture over the past two millennia. Even now, when brutal medieval aesthetics and mysticism are in vogue, and civic ideals derived from Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece are widely questioned by practices more in line with archaic despotisms, interest in ancient stories has not waned.

Olga Tobreluts. Leda. Based on the work 'Faust. Classical Walpurgis Night', 2024. Courtesy of Vladey

In March this year a large-scale retrospective by Olga Tobreluts (b. 1970) called ‘Transcoded Structures’ opened at the Ekaterina Foundation for Culture in Moscow. Today living in Hungary, her last exhibition on such a scale to take place in the country of her birth was in 2013. Her current show, consisting of different series from various years is permeated by a number of leitmotifs. And one of them is ancient myths. Tobreluts often perceives them through the prism of later interpretations and paraphrases. One of the most important series included in the current retrospective, ‘Faust. Classic Walpurgis Night’, refers to the second part of Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s famous work, which he wrote between 1774 and 1831, in which Mephistopheles leads his master to a witches’ Sabbath, transporting him back to antiquity. What was perceived as devilishness in Christian medieval Europe, where Faust takes place, was often a relic of traditional Greco-Roman beliefs. Therefore, like Goethe, Tobreluts’ Walpurgis Night becomes a time of visions consisting of ancient plots such as the kidnapping of Europa, Hercules’ curbing of Cerberus and the dazzling beauty of Helen of Troy. Outside of this series, which began in the 2010s and continues to this day, characters from ancient myths have also regularly appeared in her work. For example, the exhibition features her monumental 2017 triptych Narcissus.

The artist also explored similar themes in the early part of her career. The exhibition presents early, well-known projects, such as her 1993 ‘Gleams of Empire’ series, which reproduces somewhat obscure episodes in ancient history that eventually became myths. These works often starred Tobreluts' friends and colleagues in the St Petersburg art scene notably Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro (1969–2013), Andrei Khlobystin (b. 1962), Egor Ostrov (b. 1970), and Timur Novikov (1958–2002). All of them were in one way or another part of the New Academy, a neoclassical movement that emerged in Leningrad in the late 1980s in response to Moscow conceptualism and the new art trends in the capital, which would later be labelled by the highly conventional term ‘actionism’. Timur Novikov, who invented the New Academy and gathered a large group of artists under its banner, in addition to returning to the principles of classical art (initially quite playful and not serious), was also interested in ancient subjects. As part of an ideological struggle against contemporary art, for example, in 1991 he depicted Apollo trampling Kazimir Malevich’s (1979–1935) ‘Red Square’ in one of his famous textile works. (In general, the image of this Greek god is still used today, for example, in the drawings of Alexei Bevza (b. 1993), as a counterpoint of neoclassicism to artistic practices dating back to the avant-garde and modern art.)

In addition, Novikov was preoccupied with the figure of the Roman emperor Heliogabalus, who, both through his own efforts and a succession of interpretations from ancient writers to the theatre radical Antonin Artaud, became a myth. The artist’s Heliogabalus (1991) partly resembles his own Apollo: against a golden background on a rounded elevation stands the figure of an emperor-priest who proclaimed himself the god of the sun. The rulers of Rome were officially deified, but the extent of Heliogabalus’ auto sacralisation and other obscenities infuriated the inhabitants of the Empire: eventually, the madman was deposed and his memory was cursed.

The Roman emperor who unsuccessfully deified himself has not ceased to ignite the imagination of Russian artists. In 2016, Alexander Plusnin (b. 1981) curated a group exhibition ‘Heliogabalus’ in the pop/off/art gallery in Moscow, where the mad ruler was taken as a metaphor for social immaturity or, on the contrary, as a symptom of the simultaneous descent of the inhabitants of a country into marasmus, a symbol of the collapse of all structures and connections, a degradation into savagery and barbarism. One work stood out against the background of all the others: a life-size metal sculpture of an Amazon, with a helmet on her head, holding a shield and a spear, ready for attack. It was made by Ekaterina Kovalenko (b. 1990), a graduate of Ilya Glazunov’s ultra-conservative Russian Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, who, despite her narrow education, was at that time gradually interacting with representatives of the new wave of Russian art, who were fascinated by object-based aesthetics and oriented towards online aggregators of exhibition documentation in trendy artist-run spaces around the world.

Kovalenko's Amazon contained a paradox: on the one hand, the mythical nation of female warriors is as traditional and rooted in culture as possible, while on the other hand, in today’s realities this image takes on obvious feminist overtones and undermines the foundations. In addition, such ambiguity was found in the combination of academism and already post-modern art: made in a rough style, ‘understandable to people’, which was, in fact, a far cry from the classical tradition, as it is taught at ‘Glazunov’, the sculpture signalled the final permission to use any techniques and stylistics in the art of the second half of the 2010s. Nothing was shameful anymore, there was nothing to be embarrassed about. The antique image was placed by Kovalenko in decaying forms that the Greeks and Romans would have considered barbaric.

Appealing to ancient myths in general is extremely transgressive. In mid-March, Andrei Mitenyov’s (b. 1974) exhibition ‘Operation’ opened at the Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries in Moscow. According to the plot, scientists have decided to create a centaur by surgical means (there are even drawings which naturalistically depict the stages of the operation to create this new kind of life). Having done this, they decide to join the remaining parts together to create a centaur in reverse. The combination of human and equine parts is opposite to how this fantastic creature was commonly represented in antiquity. Mitenyov’s second centaur has a horse’s head with human legs. Non-conformity with classical models is automatically read as trauma or illness. This is why the exhibition in particular includes a sculpture where the reversed centaur sits in a wheelchair. He cannot support his heavy head on thin human legs and suffers from depression. In many ways, Mitenev’s project inherits the humanist thought behind the novel ‘Frankenstein, or the New Prometheus’ (1818) by British writer Mary Shelley (incidentally, the subtitle of this book refers to the ancient myth). There, a young physician, dreaming of defeating death, revives a body sewn from pieces of dead matter and almost immediately renounces his creation. His creation, in its turn, suffers from loneliness and inability to communicate with people because of its extremely unconventional appearance, and therefore insistently demands love, and since the creator himself is not capable of it, he wants him to make a spouse. Everything ends badly for everyone. Mitenyov’s new Promethei are also unfamiliar with scientific ethics, and simply with humanity and responsibility and give birth to two monsters: the centaur, dangerous to others, always in euphoria, and his suffering shapeshifter.

Today antique myths are more alive than ever, in spite of all fashions and trends. They do seem to be timeless. These stories both appeal to those who see the past as a role model and those who are orientated towards the future. They become an argument in favour of neoclassicism and traditionalism, but at the same time they spur revolutionary changes in art and society. And it is unlikely that any one of these parties will be able to monopolise Antiquity in the foreseeable future.

Olga Tobreluts. Transcoded Structures

Moscow, Russia

14 March – 18 May 2025

Operation

Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

Moscow, Russia

12 March – 10 April 2025