Andreeva’s Camouflage aux Fleurs

‘Les Fleurs’ at Layr in Vienna is the first solo presentation of the estate of artist Anna Andreeva whose work will also be shown at Basel Art Fair in June. Andreeva’s textile work evokes the complex relationship between figurative and abstract art in the context of soviet socialism and shows how the artist remarkably managed to salvage part of the legacy of modernist design throughout the late 20th century using nothing other than flowers.

Soft art from the cold war era, the fabric designs and sketches Anna Andreeva made at the Red Rose silk factory in Moscow form a fascinating body of work which has only begun to be understood by art historians in recent years. Her career tells the story of the complex legacy of the avant-garde in the Soviet Union, of gender hierarchies and cultural exchange during the Cold War. But it is perhaps through her use of flowers in creating a singular artistic resistance to the relentless Soviet machine that she should be best remembered.

Anna Andreeva's designs with flowers mark a radical departure from classic Soviet textiles with their bright colours and folk aesthetic and this radical approach required a game plan. Her flowers and optical grids acted as a sophisticated form of artistic camouflage. When called upon to go before the Glavsholk committee who would approve designs before production and make or break careers, Andreeva would bring a pouch filled with the paper cut-outs of flowers. Fearing that her designs might be rejected for formalism or being too radical, she would take one of the flowers and place it on top of the geometric pattern.

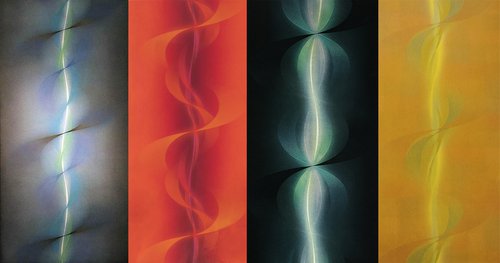

During the 1960s and 1970s optical experiments and the formal language of abstraction interested the artist most of all, and at the time these were interpreted as Western propaganda. Artists producing work in this style could quickly find their career in ruins. For Andreeva, the flowers were a ruse, she would take them away once the ideological committee had passed her new pattern and the design would go into production in its pure form. Curiously, there are even some fabrics which went into production at the Silk Factory in which the design itself includes flowers, a more enduring symbol of her aesthetic resistance.

‘Electrification’, a series she produced throughout the 1950s and 1970s has a misshapen blue and pink flower at the centre of an otherwise harmoniously structured fabric design. There occurs an awkward clash of two different aesthetic systems, the abstract and social realist figurative. This design was conceived in collaboration with her daughter Tatiana Andreeva, a mathematics student at the time who translated her mother's designs into elaborate optical formula.

Although Andreeva’s biography was deemed unconventional by the standards of the Soviet Union – she was never a member of the communist party, had come from a wealthy background before the Revolution and her husband had been in a political prisoner in a gulag - she was a highly successful artist and considered a figurehead for the prosperous silk production factory. Most artists working in a collective were anonymous, but Anna Andreeva was frequently singled out by name in part because of the success of her designs. Decorative and applied artists were regularly invited by the Union of Artists to take part in exhibitions and fairs and under the label of ‘decorative art’ they had more freedom than their colleagues ‘at the easel’. This was especially noticeable in the commissions for international fairs such as Expo Brussels in 1958 and the New York Trade Fair in 1969. The field of applied arts allowed visual experiments which were deemed necessary for the technical production of the medium as well as the low status of textiles. Her commemorative designs served as objects of cultural diplomacy at the most severe moments of the Cold War such as a silk scarf, ‘Glory to the First Cosmonauts’ which was presented by Nikita Khrushchev and Yuri Gagarin to Queen Elisabeth II during their official visit to London in 1961.

Her commemorative designs for the International Movie Festival in 1963, were presented to Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and Sophia Lauren.

Anna Andreeva's work invites us to read art history and the history of the applied arts, as a story of materiality and processs, and to explore the role of the political and ideological agendas within these processes. From astronomy to mathematical formulas and folklore in the medium of weaving and printing on silk Anna Andreeva was constantly articulating something aesthetically new and original. She incorporated official and clandestine narratives, art, technology, craft and science, as well as the analogue and digital technologies in her work. For her, the textile became a territory of experimental freedom. In the Red Rose silk factory Andreeva found both the creative scope and the material possibilities to realize her visions between art and science. Her flowers allowed her to work both in secret and yet in full view of everyone.

The research on A.Andreeva and her aesthetical resistance in the ussr has been conducted by O. Osadchy