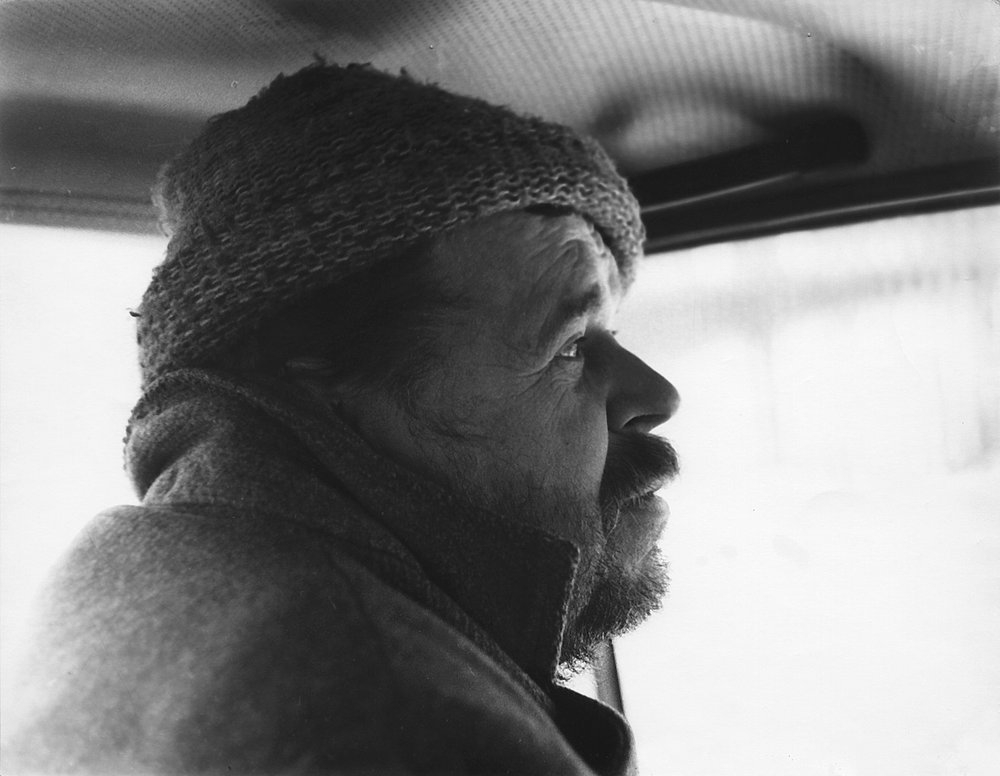

Anatoly Zverev: “Homeless and Bottomless”

The Russian art world recently celebrated the great Anatoly Zverev, who was born 90 years ago and passed away 35 years ago. Zverev was an expressionist, a holy fool and, in his own words, an apprentice of Leonardo da Vinci.

Zverev’s life and career is the stuff of legends and myths. Born into a family of veterans of the Russian civil war and raised at the height of Stalinism, Zverev (1931–1986) absorbed the trauma of those two catastrophes. Poverty meant that he never received a formal artistic education, he was expelled from an art institute because of his shabby unkempt appearance. However, he did graduate from a higher education college, where he had studied to be a decorator, which gave him more of a foundation in the arts than his reputation as an autodidact suggests.

He came of age during Khrushchev’s thaw. The resurrection of avant-garde ideas during that era is often compared to the Italian Renaissance. Just as the Renaissance strayed far from its Ancient Roman roots, Soviet non-official art was more a sui generis reinterpretation of the avant-garde, than its direct outgrowth. Zverev became a key figure in the first wave of that second avant-garde, which coincided both chronologically and ideologically with American post-war expressionism.

It was not by chance that David Alfaro Siqueiros, the Mexican star of Social Realism, who visited the Soviet Union during the Festival of Youth and Students in 1957, awarded Zverev the grand prix, seeing him as a Russian Jackson Pollock. As colleagues recalled, Zverev was flattered by the comparison with the “shaman” artist. He played along and reinforced the idea with his outlandish behavior: painting in public, making poetic improvisations, shouting in public places and even appearing naked on occasions.

“Armed with a shaving brush, kitchen knife, gouache and watercolours, while singing for a rhythm,” wrote Dmitry Plavinsky (1937–2012), artist and friend of Zverev. “He threw himself at the paper with a half-litre jar, spilling dirty water all over the paper, the floor and the chairs; he flung jars of gouache at the puddle, and spread the colorful nightmare all around with a rag and sometimes even a shoe; he slapped the paper with the shaving brush, scratched lines in it with the knife and, before your eyes, would appear an aromatic bouquet of lilacs, or the face of an old woman looking through the window.”

During that crucial year of 1957, all the elements of Zverev’s artistic life came together: a sense of freedom, restlessness and a wealthy patron named George Costakis. Soon, the art he showed in closed Moscow apartment exhibitions migrated across the Iron Curtain. Thanks to another generous collector named Alexander Gleser, exhibitions of Zverev’s works were held almost every year in France, West Germany, Austria, Switzerland and North America. But recognition abroad only seemed to accelerate his breakdown at home. He led an “anti-social” lifestyle, often spending nights on the streets. His own myth-making, the creation of the persona of artist as genius, came with lots of drinking, which eventually deepened into the alcoholism that led to his sad end in a lonely apartment on the outskirts of Moscow. He entered the ranks of holy drunkards, along with martyrs of Dostoyevsky’s prose and the lyrical heroes of Venedict Yerofeyev.

Another myth about Zverev is that of his prolific creativity. His contemporaries recalled that in exchange for good company and a bottle of vodka, he was happy to paint portraits for even little-known drinking buddies. According to rough estimates, by the age of 55, Zverev had created around 30,000 works. During the last 30 years, more than a thousand were sold at auction, according to artprice.com. The most expensive work, a portrait of Vladimir Nemukhin (1980), sold for only $46,000. As it was during his life, during his death, demand for his works has been stable. But, Zverev’s free-wheeling style also provoked the production of many fakes. Katherine Ponomarenko, a PhD art historian and expert at P.M.Tretyakov Expertise, says that this independent laboratory in Moscow receives inquiries regarding three to five works by Zverev each month; only about five percent have ever turned out to be authentic.

In 2013, the Museum of Contemporary Art AZ was founded in Moscow, based on the collection of the art patron Natalia Opaleva and a gift from Aliki Costakis, the daughter of the late collector and friend of Zverev. Along with research and exhibition activities, the museum also established a Zverev Art Prize to mark the artist’s 90th birthday, with a fund of five million roubles - approximately $67,000. The prize’s slogan, “Art is free, but Life is in Chains”, is a fitting epitaph to the life and art of the great Anatoly Zverev.

I Love Zverev

Moscow, Russia

December 1, 2021 – May 29, 2022

Anatoly Zverev. The forest should be here

Moscow, Russia

November 23, 2021 – January 30, 2022