An Avant-garde treasure trove in the heart of Asia

A museum in the city of Nukus in Uzbekistan has become a sanctuary of the Russian Avant-Garde, thanks to its enthusiastic director-founder Igor Savitsky. Yet, in post-Soviet times, the fate of its unique collection has sparked controversy. Russian-British artist and art historian Ariadne Arendt gives her account of the past and present of a place whose history has become a part of her family lore.

I was the only woman, aged 20, and the only non-Uzbek, it seems, on a night flight to the distant mysterious city of Nukus in the unpronounceable Karakalpakstan (an autonomous republic in the Northwest of Uzbekistan), former Soviet Union. My mission: to explore the Savitsky Museum, a legendary institution hidden away betwixt three deserts, a treasure trove of Russian avant-garde art I’d heard about from family lore. Armed with my laptop and camera (hidden in my luggage from suspicious Uzbek customs), I felt like a conquistador, albeit a rather scared one. The museum is what Russians might call – widely known in narrow circles – the stuff of myth, incredibly the second largest collection of Russian and Soviet avant-garde art of the 1920s and 1930s, second only to the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and yet hidden in a corner of the earth, known otherwise only for the Aral Sea environmental disaster. Few people have ever been there and scant information was available. So how did some 90,000 artworks end up in this middle of nowhere?

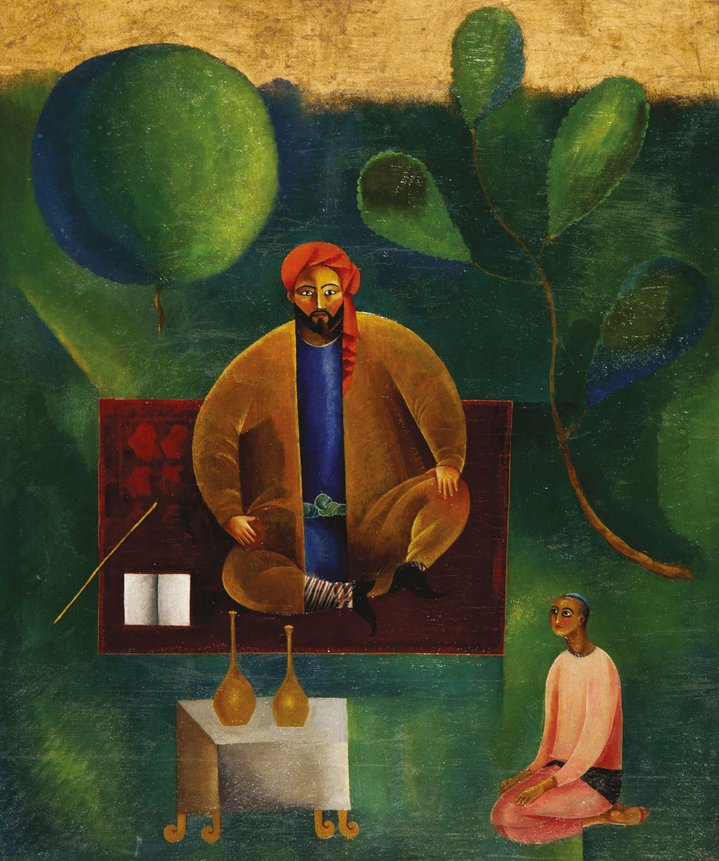

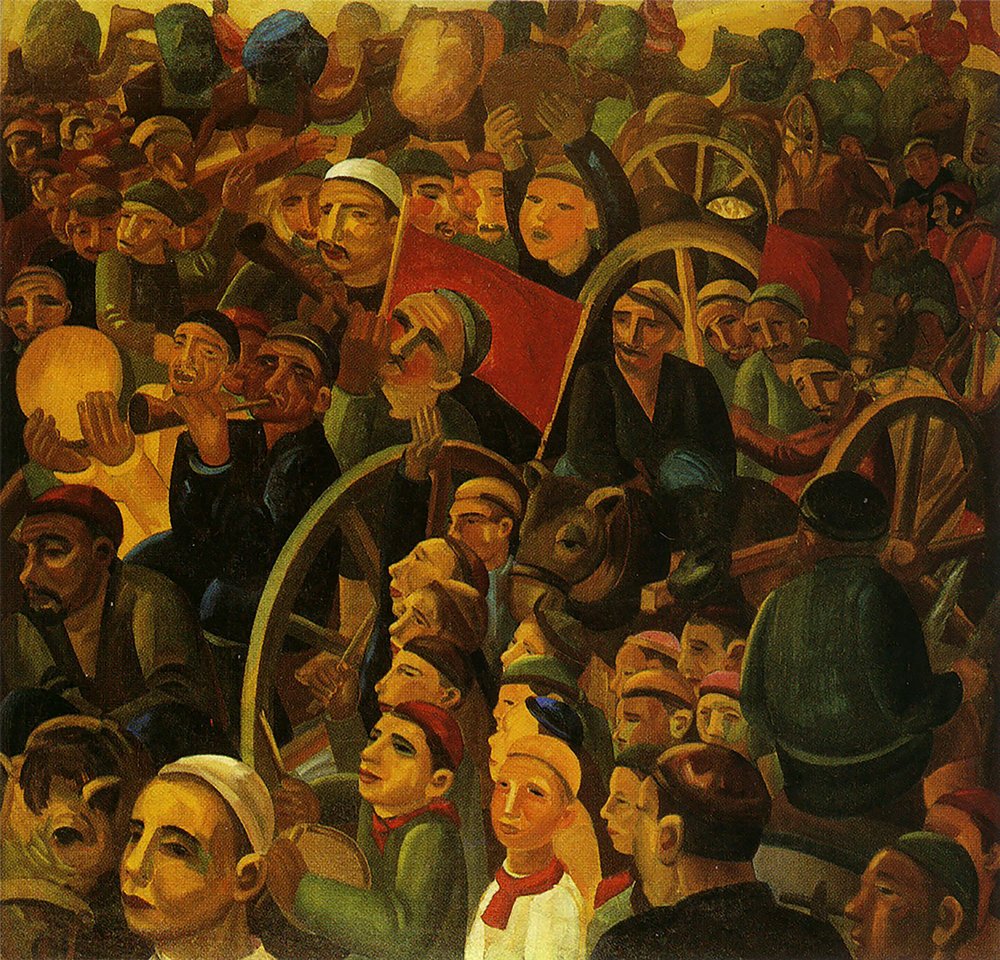

The museum’s founder and single-handed genius of undercover collecting is the key. Igor Savitsky (1915–1984), progeny of an aristocratic lawyer’s family, who, following the revolution, trained in the proletarian profession of electrician, but eventually followed his leaning towards the arts, studying at one point under Robert Falk (1886–1958). In 1950, he first joined an expedition to Central Asia as an artist sketching archaeological digs and fell in love with the steppe, returning again and again and eventually settling for good. Discovering a goldmine of local folk arts and crafts of the Karakalpak people which needed rescuing, he began collecting to the bemusement of locals, who dubbed this eccentric Russian a rag-and-bone man. Instead of exporting his finds to the capitals, he dreamt of founding a museum right there in the desert and after much graft and some good fortune, in 1966, he secured the permission and funds to open a museum, which became his life’s mission. Soon, he spread to collecting central Asian art and himself catalysed its production, inspiring a wave of artists in Karakalpakstan. Realising the potential his museum and favourable location had, he took the risk of collecting prohibited works, banned by censorship for their so-called formalism or any other sin of which the soviet system had no shortage.

“It shows not only the artistic history of one place, but a cultural exchange between Russia and Central Asia, which was only possible within the political structure of the Soviet Union. Here, Moscow stood at the centre, Uzbekistan at the periphery and Nukus in so remote a position that even the steely grip of the central powers could not reach it with its full strength,” writes Aliya Abykayeva-Tiesenhausen, scholar of Central Asian art. His cause gained momentum and he worked tirelessly amassing huge amounts of art over record time. The unbelievable paradox being that Savitsky managed to use government funds in order to purchase and rescue huge quantities of the very things the government had prohibited.

My grandfather recalls Savitsky’s visits in the mid-1970s. An unexpected knock at the door one day resulted in a lasting friendship. He would spend several months in Moscow and much time in our home (where, incidentally, I am sitting, writing this now), in the Maslovka artists’ village, where he was always a welcome guest, scouring attics and visiting artists and their relatives. Spending months at a time amassing as many works as he could take back, seeing him struggle across the courtyard battling the famous winds with armfuls of rolled canvases, my grandfather remembers rushing down to help him. And seeing him off on the long train journey back to Nukus, a compartment stuffed floor to ceiling with his precious cargo.

He rescued many works not ever dreaming a time would come when they could be displayed. Possessing impeccable taste, he relied primarily on his intuition. As a result, the collection contains some of the brightest examples of avant-garde artists, but also crucially, unique groups of works by otherwise unknown artists, who survived exclusively thanks to Savitsky and whose works still need the attention of scholars. Savitsky died an untimely death, due to unfortunate experiments in cleaning bronze artefacts with formaldehyde, a victim to his own passion. After his death, the director became Marinika Babanazarova. Of local origin, she had been friendly with Savitsky since her childhood through her father, an academic and party functionary, who helped Savitsky succeed in his mission. Babanazarova helmed the museum for 32 years, revealing this treasure-trove to the world after perestroika, bringing the collection to international renown, she is responsible for the moniker “Louvre in the desert” and, above all, a devout and meticulous defender of the collection’s integrity and safety. All the more surprising came an accusatory campaign, claiming that several works in the collection were suspected forgeries and the originals had been sold. No confirmation or evidence of these accusations was ever brought to light, nevertheless they forced Babanazarova into signing a voluntary resignation in 2015.

The scandal catalysed a movement, which brought attention to the dangers of Uzbek and Central Asian heritage and the observatory ‘Alerte Heritage’ was set up by independent scholars Boris Chukhovich and Svetlana Gorshenina, with the aim of cataloguing museum works and safeguarding public cultural assets. What happened there, I ask them – could Babanazarova have really been involved in illicitly smuggling works from her museum and replacing them with fakes? The answer is a resolute no. But, Chukhovich interjects, “This raises the legitimate assumption that if Marinika Babanazarova was forced into resignation, perhaps whoever stood behind the accusations were themselves interested in committing the acts for which they incriminated her: namely theft or forgery of certain works held within the museum? And this suspicion falls on the committee investigating the museum holdings after her removal.” This question remains to be answered. It requires a meticulous inspection of the holdings and, in a country renowned for high levels of corruption and close connection between power and crime, this uneasy task falls on the shoulders of the museum’s recently appointed director.

Following an international call-out, Tigran Mkrtchev – an archaeologist specialising in oriental art and with a background in Moscow museums – was appointed and assumed his post at the beginning of the year. Now faced with a dream job of heading one of the world’s most unusual art museums, with perhaps the biggest growth potential – the task is undeniably gargantuan. The problems are exhaustive and impressive enough to almost rival the jaw-dropping collection: tricky politics, lack of funds, dire need for conservation and restoration (with no qualified specialists in Uzbekistan), building renovations, bureaucratic hurdles. It’s a heavyweight balancing act, especially so following over five years of Babanazarova’s absence, which are rumoured to have catalysed further deterioration. When I ask romantically about his future plans and dreams, Mkrtchev puts me in my place that the majority of his tasks are plainly pragmatic: temperature control, cataloguing, securing sponsorship, renovations, bureaucratic hurdles. And yet, he makes room for an unlikely project: “Our museum contains works of local Karakalpak artists. Our own. Which no one has taken seriously... Noticing this, I gathered the fine art department personnel and set them the specific task to begin a purposeful study of the work of Karakalpak artists. I am sure that this will bring interesting results.”

An unusual trump card to play for a museum holding superstar names like Lyubov Popova (1889–1924) and Robert Falk (1886–1958). But his message is clear: he is devoted to the region. With the museum being where it is, the question always hangs of whether or not the collection would be better off elsewhere. But these works owe their existence to this far-removed corner and their duty to honour the land which harboured them is to remain faithfully here. And if their location brings in problems, which undeniably it does, this is the burden they must bear. After all, this museum is sadly the only thing of value this region and its people really have, not something which can be said of any great metropolitan museums.

The State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Karakalpakstan named after I.V.Savitsky