Alone, together: reflections on Collective actions

A group of conceptual artists who quietly defied Soviet lifestyles in the 1970s is still staging its cryptic outdoor performances nearly half a century later.

On March 13, 1976, thirty individuals gathered in a snowy clearing in Moscow’s Izmailovsky Park and waited. Eventually, two individuals appeared at the edge of the wood. They crossed the field to meet the group and distributed typed slips for each person to sign, certifying they had witnessed an “appearance”. Upon receiving their “verification documents”, the participants were left to disperse and consider what, if anything, had actually happened.

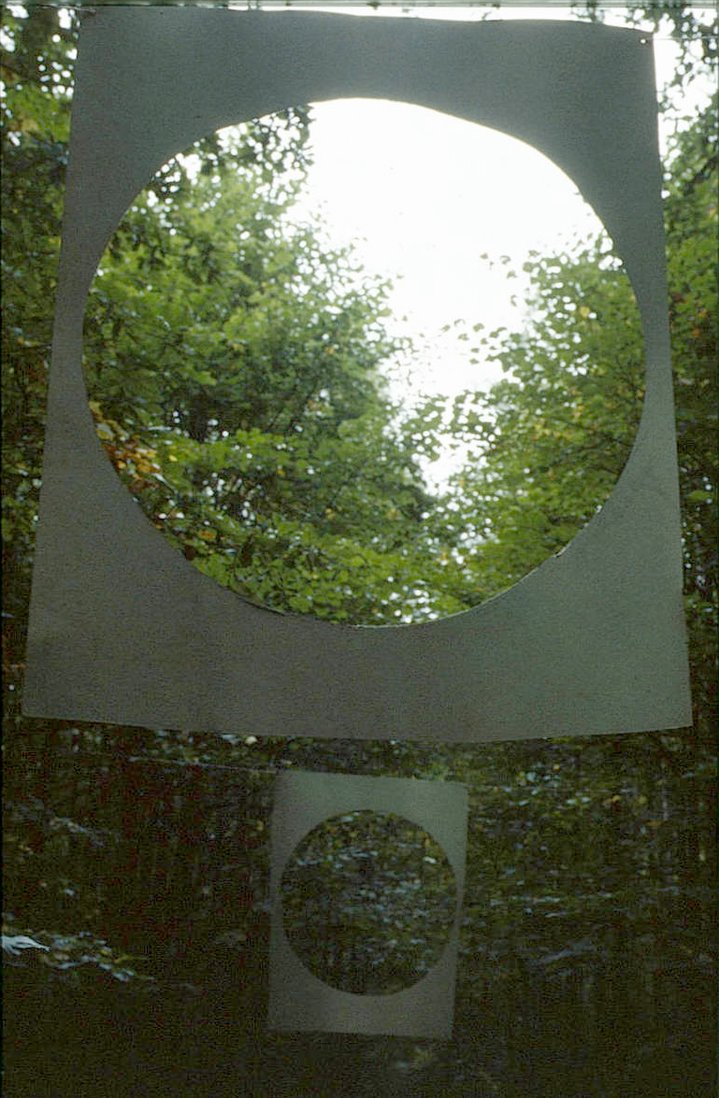

In fact, nothing had really occurred — and that was the point. This initial uneventful event would become the guiding concept for over 150 performances that the Moscow-based art group called ‘Kollektivnye Deistvya’ (“Collective Actions”) has since organized. Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949), one of its founding members, has theorized these minimal gestures as “empty actions”, created in the hope of stimulating thought and collective discussion.

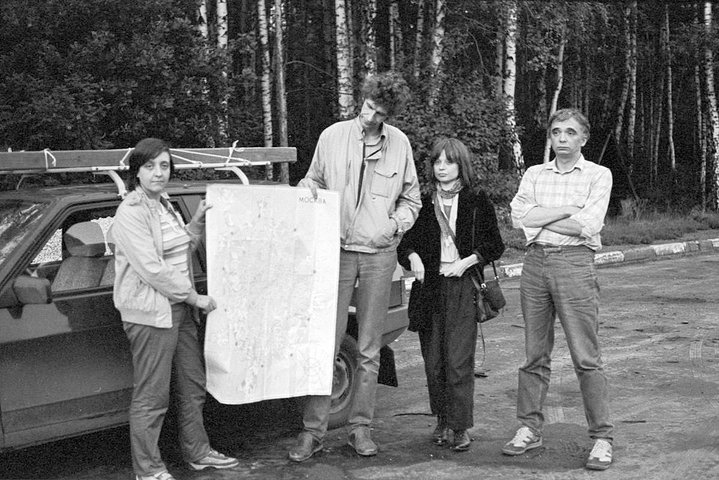

Over the years, a shifting constellation of visual artists and writers, among them Lev Rubinstein (b. 1947), Nikita Alexeev (b. 1953), Sabine Haensgen (b. 1955), Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), Boris Groys (b. 1947), Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933), and Georgy Kiesewalter (b. 1955), pursued the potentials of emptiness.

Because the group was formed in the ideological context of the Soviet Union in the 1970s, such ambiguity was a provocation. A man with a balloon-head that burst just before he disappeared? Being told to fully unravel a spool, only to discover the thread itself was not attached the spool? The group’s performances mixed surrealism with pranks that revealed the paltriness of Soviet officialdom. Participants were usually summoned by phone or word of mouth. Elements like the signed testimony in ‘The Appearance’ would pit the validity of one participant’s experience against what was written on paper, thus setting in motion a debate about what they had supposedly seen or heard.

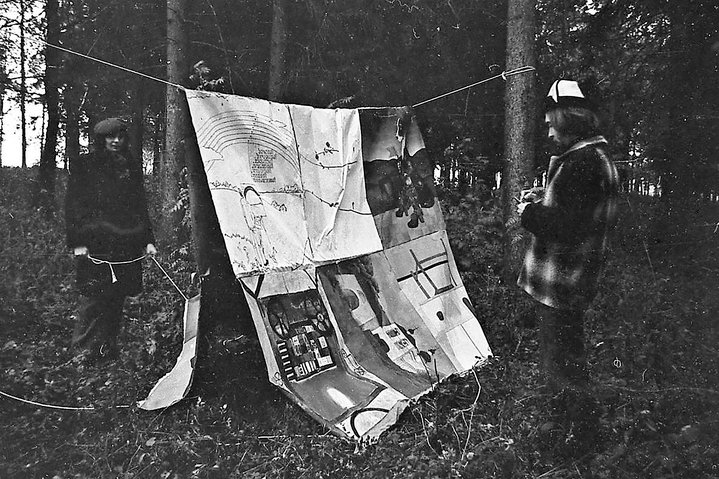

Collective Actions also did away with the one-artist-one-object model of creation. As part of a larger art movement known as Moscow Conceptualism, the participants gave priority to theory over objects, thus resonating with contemporaneous Minimalist and Conceptualist movements in Western Europe and the United States.

The group has also proven inspirational for a later generations of Russian performance artists, encouraging them to make streets and forests their canvases. It still organizes actions, maintaining the outdoor group format in order to revisit themes of past works. This process remains important to Monastyrski, who says that he continues to find inspiration “in the past, in archives, as well as in video poetry”.

“We began with a pleasantly playful exit from everyday Soviet reality. Over time, we were able to carefully develop a concept and, as one hopes, introduce many elements into our works which were new at the time. One of these ‘surplus elements’, for example, was a change in the consciousness of the audience over the course of an action, which could last anywhere from several minutes to several weeks and even months,” Kiesewalter recounts.

A poet and writer, Kiesewalter also photographed many of the performances. Around 1980, the group began incorporating his images and other documentary materials into hand-bound volumes called ‘Poezdki za gorod’ (“Trips Out of Town”). These became the focus of subsequent conversations among participants and critics, thus literally and metaphorically unfolding actions over time. Considered today, when many of us remain homebound, that practise reminds us that isolation can also be a space of promise, where we might find ourselves alone together.