Alexander Chernousov’s journey from documentary film to documentary comics

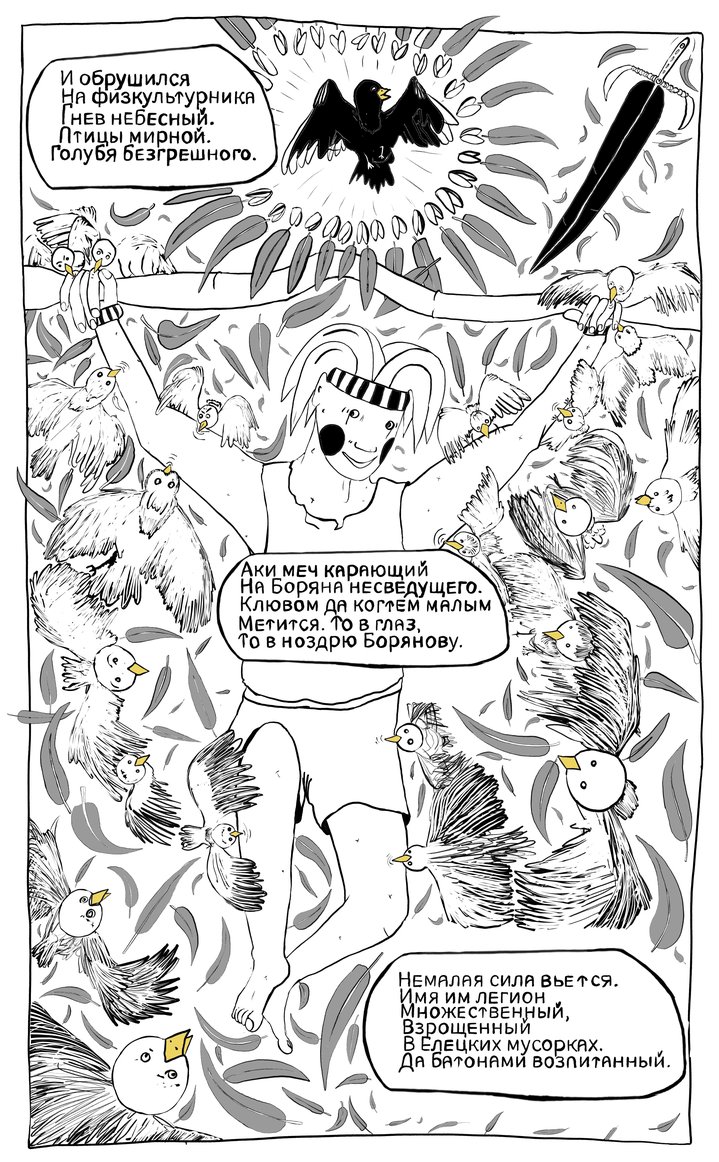

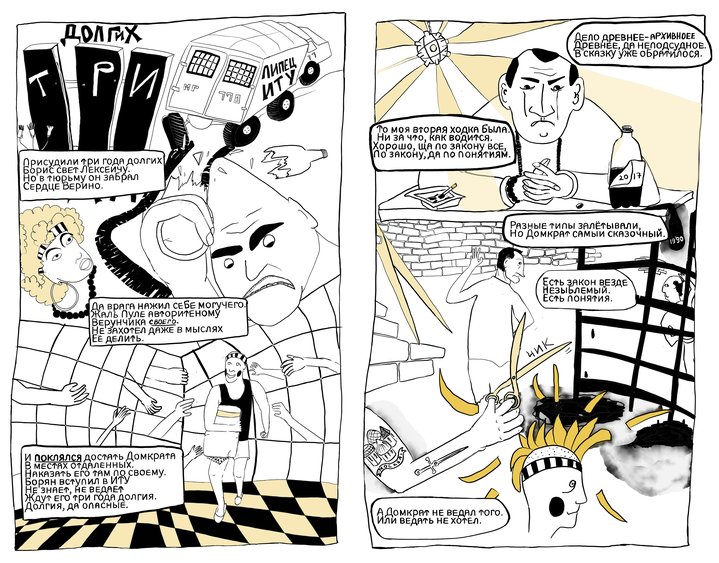

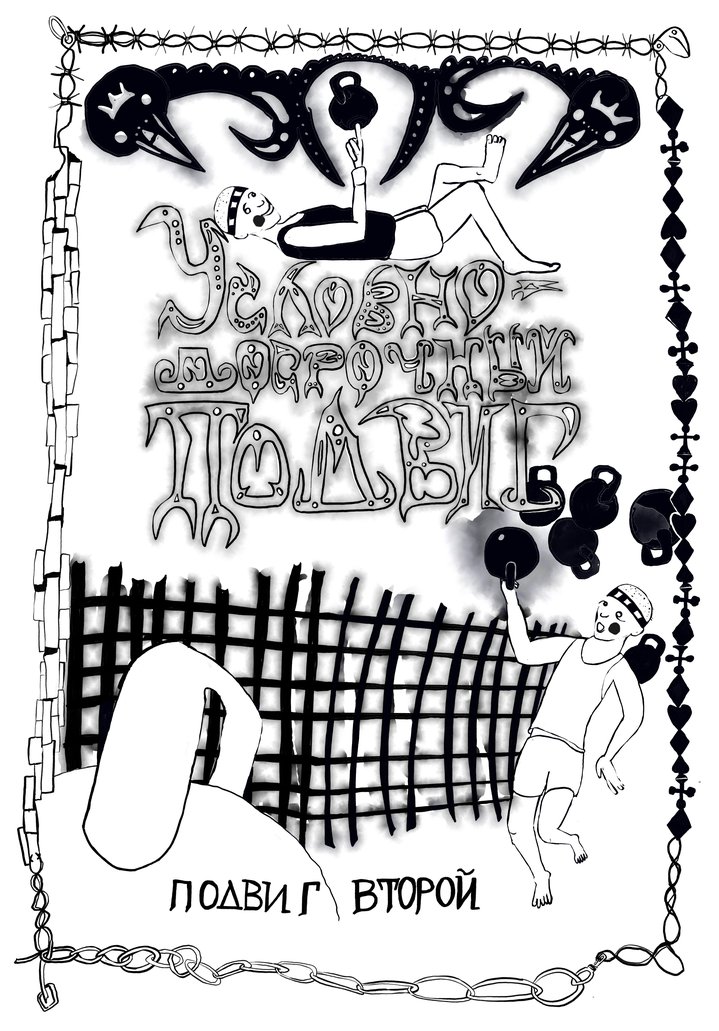

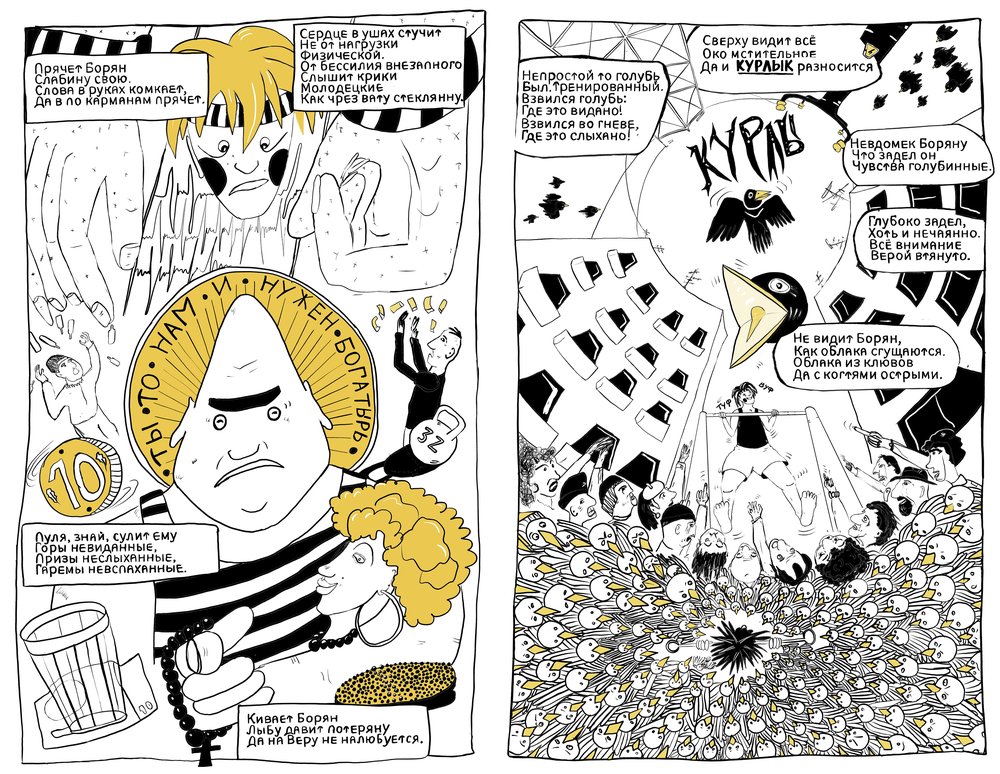

Alexander Chernousov. Page from the comic strip 'Labours of the Mighty Carjack', 2022. Courtesy of the artist

This theatre and film director turned artist from Moscow living in Oregon, US, is best known for his artsy comics about a forgotten Russian hero of the 1990s. The first two chapters are about to be published in the USA. Russian Art Focus is previewing a few fragments before its official release.

Today fascination with real stories told by real people is on the rise in the world of post-truth. People are increasingly tired of manipulated media images and carefully crafted plots mass-produced by the entertainment industry and even for those with a media background, this desire for the truth can sometimes become an obsession. Alexander Chernousov (b. 1978) started out as a screenwriter and director, yet quickly discovered that he preferred telling real stories over inventing fictional ones. He directed several documentary films that won prizes at industry festivals. And then, a few theatre performances in which he used the technology of headphone verbatim, where actors repeat pre-recorded speech of their characters, with all its mistakes and imperfections, while listening to it through their air pods instead of learning the text by heart. His latest two productions have been in North America in the Autumn of 2022, dedicated to the Russian-speaking diaspora living in the states of Oregon and Washington.

His documentary comics called ‘Labours of the Mighty Carjack’, stemmed from a documentary screenplay outline that had been rejected by several producers. ‘I stumbled across the story of a 1990s Russian strongman and got hooked on it’, he recalls. ‘Yet the producers told me nobody cared about the 1990s anymore. Maybe they were put off because the outline was written in the rhythmic prose of bylina, an ancient Russian folk ballad’. Chernousov, was an avid reader of comics for many years yet never tried to create one himself, when he decided to switch to this medium.

However, in both visual language and subject-matter his work is far from the conventional superhero graphic novels. ‘For me, this work is a story of why superheroes don’t survive in Russia’. Indeed, his protagonist Boris Gridnev, also known by his nickname Carjack, was an ordinary human harboring a secret superpower. His amazing feats of strength and endurance made twenty-one entries in the Guinness Book of Records. ‘What drew me to this character most was the fact that his feats were totally pointless’, Chernousov admits. Gridnev managed to move a lorry by tugging it with his teeth, and deciding this was not enough, he did the same with an airplane. ‘He inspired a lot of people and there are several societies of power-lifters named after him even here, in America,’ Chernousov says. ‘President Boris Yeltsin gave him encouragement by opening a ‘Theater of Strength’ in his hometown and presented him with a saber engraved with the words ‘From Boris to Boris’. Chernousov was captivated: ‘you can see how it was totally impossible for me to pass by a story like this!

Sadly, these exceptional powers did not help Gridnev himself in the end. He passed through all the circles of Russian 90s’ hell: he joined a gang of mobsters, got into jail, and even worked as a sports teacher in a secondary school, but eventually he was shot to death on the street by an unknown offender at the age of 36. This superhero-loser was long dead by the time Chernousov heard about him, yet he managed to find and interview a few people who had known Gridnev in person. Thus, various chapters of the Carjack comics have different narrators, more in the traditional spirit of documentaries and not typical of comic books. Even more unusual is the composition of a page itself. Instead of the rigid sequence of frames you see in comic strips or conventional graphic novels, he uses a ‘free flow of image over the page’ as Chernousov puts it. A style evocative of tattoos on the backs of Russian prisoners where you can read about their life story from their back, using the simple set of symbols and codes, for example, church cupolas symbolize a man’s prison term. ‘Each page is a sort of an ornamental work that can be read like a tattoo, in different directions, not just from left to right’, as the artist explains. ‘When I finish working on a page, from the beginning to the end, I insert the text and try to guess what ornamental details are missing, which might evoke a sound, or a smell or a merely the sense that time has passed. Then I add these details to enrich the ornamental texture of the page’.

The text follows a similar principle of joining opposites together. The hypnotic rhythm of the Russian bylina collides with the vernacular of prison cells and backstreets, a mob jargon that is pervading even the official rhetoric of Russian propaganda today. ‘I wanted conflict to exist within the text itself,’ Chernousov says. Referring to the producers who criticized the story for its perceived lack of relevance, the artist points back to the 1990s and goes there in search of clues that might in some way explain the current events in Russia. ‘This story evokes the life of people in the 1990s and how out of such a set of interesting, absurd, and weird things emerged all that is happening now. For me there is no question as to why it came about. I answer that question for myself in these comics.’

The first two episodes of Labours of the Mighty Carjack will be published in Kodes, a collection of documentary zines published by Portland Institute for Contemporary Art.

Portland Institute for Contemporary Art