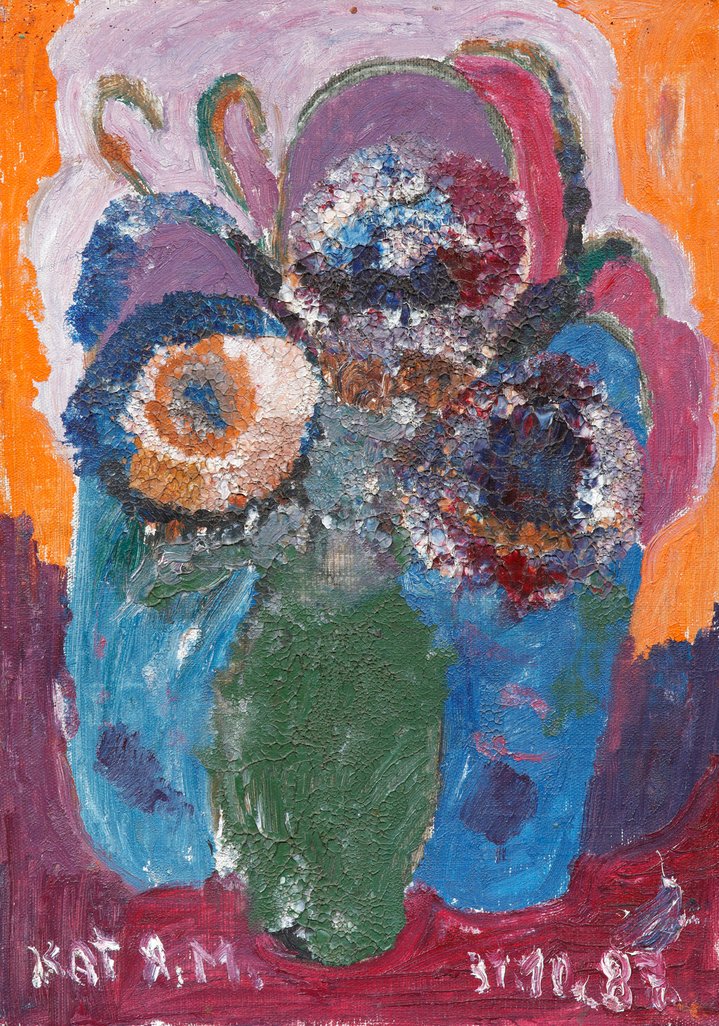

A world of one’s own: the escapist imaginings of Soviet women outsider artists

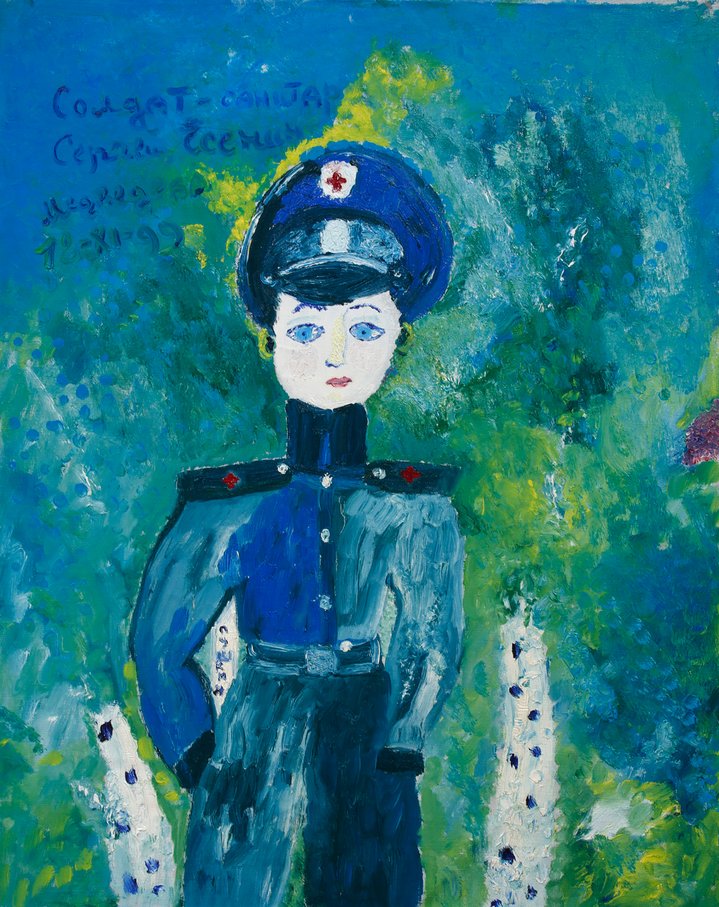

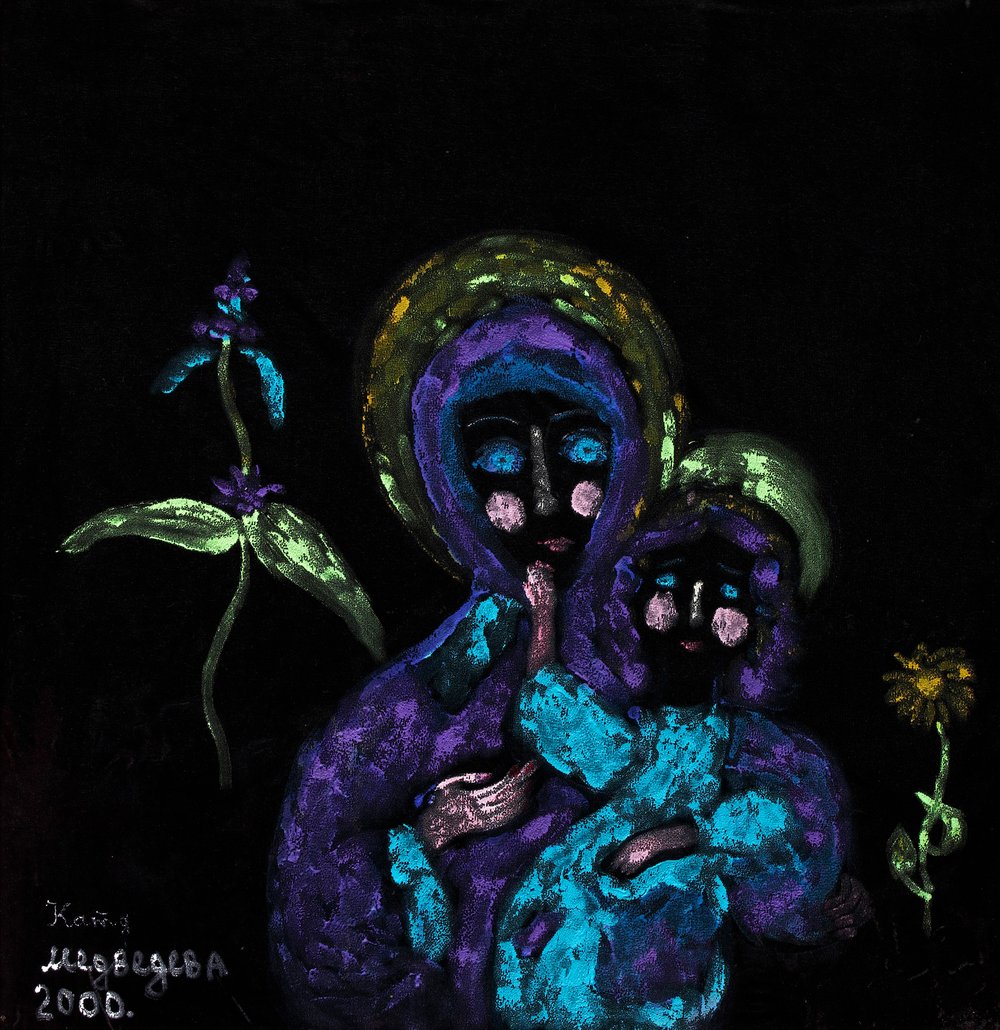

Katya Medvedeva. Mother of God. Courtesy of Bogemskaia — Turchin Collection

A Woman’s lot was often harsh in the Soviet Union and quite a few found refuge in art, often at an advanced age, even managing to get their fifteen minutes of fame into the process.

Soviet women had a reputation for being tough, hardened by daily realities their European peers could not imagine. Yet this produced a rich constellation of self-taught female artists who turned inwards, using their imagination to create the worlds they wanted to inhabit. Women such as Maria Prymachenko whose work was recently exhibited at Venice during the Biennale, left startling bodies of work which are now finally being reappraised by art historians globally. Who are these exceptional women whose names were once a postscript to art history?

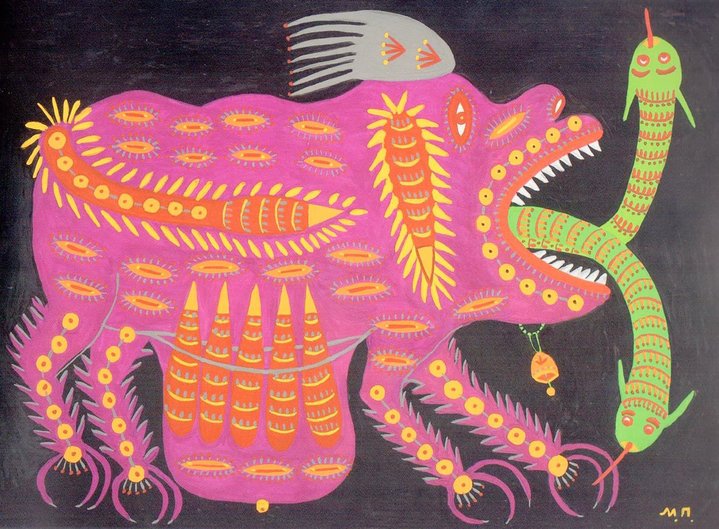

Maria Prymachenko. A Dragon Descends on Ukraine...1987. Paper, gouache. Croatian Museum of Naive Art

One lesser known phenomenon of Soviet culture was that of self-taught artists. Naïve, primitive, or outsiders – there were talented, solitary figures who created pictures and art objects in response to an irrepressible inner drive. Whether living in remote villages or anonymous tower blocks, the vast expanse of the empire was dotted with these idiosyncratic talents working relentlessly over decades from their hidden improvised home studios. With no artistic training or art historical knowledge, they were outsiders to both officialdom and underground bohemia, yet they pursued an artistic calling which was rooted deep within.

Women had a special place as the torch-bearers of decorative, applied and folk art traditions. Artforms like embroidery, pottery, painted houses and decorated wooden furniture, were being kept alive by older generations of women naturally connected with these roots; it passed through generations. And now, once seen as the most peripheral of art forms, today applied art long associated with female mastery is finally coming into the mainstream. There were also male outsider artists of note, such as Pavel Leonov (1920–2011), Alexander Lobanov (1924–2003) and Vasily Romenenkov (1953–2013) however unlike in the field of Soviet non-conformism which was dominated by men, here female artists are more than equal partners.

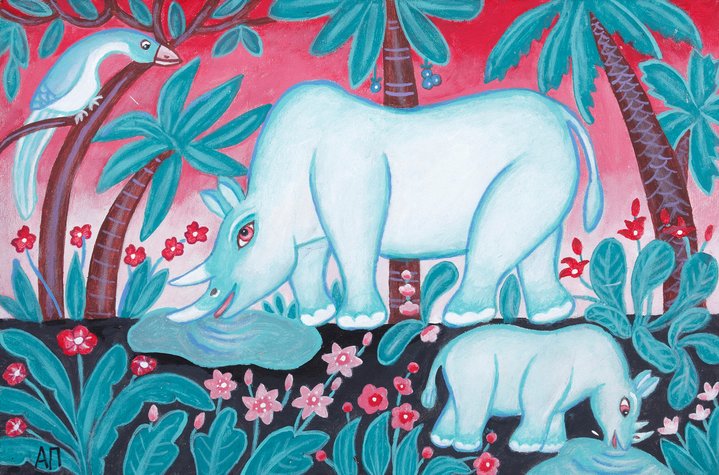

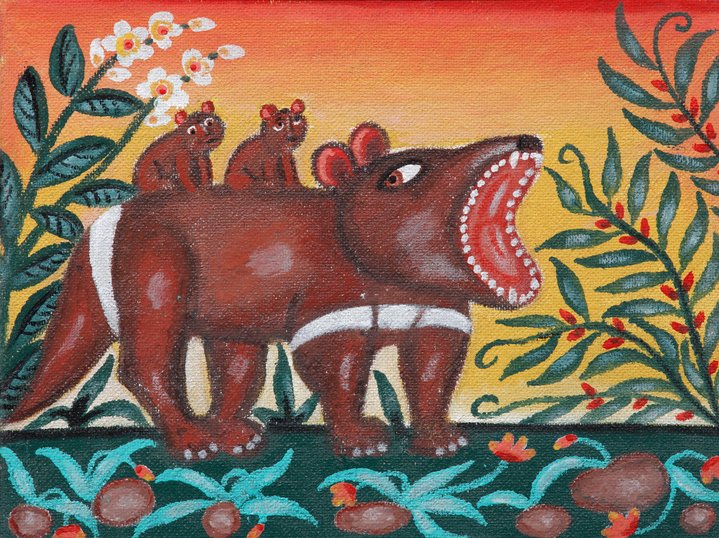

Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko (1909–1997), whose work was recently exhibited during the Venice Biennale in the main pavilion curated by Cecilia Alemani, is known for brightly coloured idiosyncratic paintings bursting with decorative outlandishness and fantastical creatures which could be read as surrealist visions or as pages taken out of a medieval bestiary. “I bow down in front of the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian”, said Pablo Picasso, when he encountered her works which against all odds made it into the most established and political show of the times, the Soviet Pavilion of the International Exposition in Paris in 1937.

Of course, Prymachenko’s imagery is not as innocent as it might seem on first inspection. Her exuberant ornamental flowers and mythical monsters hide an equally deep horror behind their façade. Prymachenko contracted polio as a child; she drew her first pictures with a stick in the sand while looking after geese in her village; her mother taught her how to embroider. In her early twenties she witnessed Holodomor, effectively a genocide by starvation engineered by Stalin which killed several million Ukrainians. At this time she began to paint. In 1937 Stalin unleashed his great terror. Shortly after, the Second World War took Ukrainian history into its hands with losses of millions more lives, including those of Prymachenko’s husband and brother. Wave after wave of death and destruction unrolled on the steppe, an otherwise breathtakingly beautiful landscape which stretches for miles into the horizon in all directions.

Prymachenko’s flat images each conceal different layers of meaning and emotion. In essence they are a battleground between a dreamlike world of a Ukrainian decorative arable idyll and the real, unspeakable (but perhaps paintable) horror she witnessed taking place in her homeland. Monsters are an incarnation of evil, their image emerges from an archaic tradition, beasts with rows of deadly teeth, multiple heads, legs and other body parts. These all set jarringly against a conscious, almost stifling optimism which radiates through colour and pattern.

In the 1960s and 1970s Prymachenko enjoyed a period of stability and some recognition, and she moved from working in watercolour to gouache. But her village was 30km from Chernobyl, and in 1986 the nearly eighty-year-old witnessed another vision of hell, which she reflected upon in her last works.

Today Prymachenko has become an icon, celebrated by UNESCO, with commemorative coins and stamps, there is a boulevard named after her in Kyiv and even a minor planet in outer space. The personal tragedies she experienced during her life continue over her legacy. A museum in the Ukrainian town of Ivankiv with a large holding of her work was reportedly burnt down at the beginning of the invasion, in February 2022. Rumours abound that a local hero ran into the blazing building, risking his life to rescue the works, and she has since also become a symbol of resistance.

In the Kherson region of Ukraine, on the banks of the Dnieper river in a small town called Tsuryupinsk there is a cottage which can only be described as magical. It is painted from top to bottom, every wall, ceiling and windowsill, every surface is covered with fantastical plants, birds, animals and people. It is the extraordinary work of Polina Rayko (1928–2004), who first picked up her brush just before turning seventy, and then was unstoppable. Locals took her to be insane, spending her small pension on art materials, the cheapest household paint and basic brushes.

Rayko witnessed the war as a teenager, married in 1950 and had two children. The family was self-sufficient, living modestly from their own orchard and cottage garden, but life was tough and her husband and son became alcoholics. Tragedy struck when her daughter was killed in a car accident in 1994 and her husband died the following year. Her alcoholic son was in and out of jail, stealing and attacking his mother, and was eventually sent to rehab where he later died of cirrhosis. After his death a neighbour suggested she paint two doves to help her express her grief and Rayko found her real calling in life.

Each room in Rayko’s small cottage is a complete, unified composition and yet the paintings are intuitive and free. She takes her imagery from dreams and memories, the surrounding landscape as well as chocolate boxes, postcards and wine labels. Members of her family are painted alongside nurses and mermaids, fish with beaks, the road to heaven and the afterlife. Pagan symbols and archaic ornamental traditions, sit side by side with religious imagery, Jesus, Mary, orthodox crosses, Soviet stars and World War II symbolism.

Muscovite Alevtina Pyzhova (1936–2021) was drawn to art from an early age, however, was denied entry to art school for being partially blind. Her artistic career took off in 1999 when she was discovered by the art historian Ksenia Boguemskaya, a pioneering champion of naïve and self-taught art in Russia, who helped many artists in their self-discovery and built understanding and public recognition for them in their homeland. Pyzhova was discovered in the 1990s when Boguemskaya organised a talent competition on Russian TV.

Pyzhova’s work has the decorativeness and bright colours characteristic of many naïve artists, however, it stands apart for its eroticism. The nude body and sexuality in general were highly taboo in the Soviet Union, according to the famous catchphrase “there’s no sex in the USSR.” After glasnost, this led to a strong outpouring of sexual energy in various creative media in the 1990s, most often by men. Pyzhova, who once claimed Vysotsky among her past lovers, is a lone figure in this respect, representing a channel of all of the repressed sexual energy of Soviet women.

Katya Medvedeva is probably Russia’s best known female naive artist. Born in 1937, her parents were declared kulaks [wealthy landowning peasants] and subjected to repression, dying of starvation when Medvedeva was nine and she ended up in an orphanage in Azerbaijan. Incredibly, despite food and clothing shortages after the war, she has fond memories of this time. For years she travelled around Russia doing odd jobs when at 39 she ended up in Kislovodsk in a theatrical prop department. She noticed an art class in the neighbouring building, the first time she had seen anyone paint. It was such a watershed moment in her life that she now counts her age in years from the date she started painting. “It’s when my life really began”, she says.

Medvedeva moved to Moscow in 1988 where she consciously embraced city life, its artistic circles, and discovered high culture such as ballet, which has become a lasting leitmotif in her paintings. Her imagery comes from life and television, equal sources of visual inspiration. Extremely prolific, Medvedeva became a well-known public figure, and with it found a certain level of commercial success in Russia.

If Prymachenko and Medvedeva have achieved a status at least among the Ukrainian and Russian public of wide affection and fame, there are several other names, lesser known yet just as fascinating. Lyubov Maykova (1899–1998) was a reclusive villager who began painting at 79 and was discovered by accident one day by a visiting artist who came to her to buy some pickled mushrooms. Elena Volkova (1913–2013) from eastern Ukraine, having grown up in a rural idyll surrounded by water, nature and village traditions, suffered injuries and the death of her husband in World War II. She began painting at the age of 45, borrowing her son’s school art materials, and through her works she revisited the memories of her childhood creating out of them a personal paradise. Zinaida Babina (1915–1995) came from a large family of old believers in the Vyatka region, as a pensioner she began creating modest works on paper in a restrained palette uncharacteristic for naïve painters, some strikingly echoing post-impressionists such as Vuillard. Anna Dikarskaya’s (1893–1982) paintings fuse daily life and fantasy in what might be called socialist magical realism and there are Irina Eremko’s (1919–2007) fantastical trees.

Common chords ring out among these distinctive figures: overt optimism, a childish naivety, representations of festivals and beauty, earthly paradises. However, there is a double-edge: as Ksenia Boguemskaya comments, “these images should be considered as compensation for those trials, the poverty, the cruelty of existence that befell the artists from the people.” There is something in their work which can be seen as the search for a refuge from hardship, the creation of an artificial space filled with aesthetic beauty and wilful hope.

It is extraordinary that most of these women artists experienced the absolute height of their creativity in old age. The 1970s till the 1990s were decades which saw a flourishing of self-taught artists, final, transitionary years of the Soviet Union when the grip of state censorship was looser and there was an increase in personal and economic freedom. It was as if there was a sudden burst of pent-up creative activity after the sufferings of earlier years.

Now aged 85, Medvedeva is among the last of these artists, this generation of soviet self-taught artists is dying out. Moscow’s Museum of Lubok and Naïve Art is being unfavourably reorganised, its incredible collection of almost 5000 items now awaiting an uncertain fate. The end of an era of bright idiosyncratic stars, who took up the paintbrush against all odds, battling the surrounding demons through art, a testament to the true power of human creativity and imagination.

The author would like to express her thanks to Alexei Turchin, expert in Soviet naïve and outsider art.