A Garden of Converging Paths

Vladimir Seleznev. Metropolis Cologne, 2024. Installation view. Courtesy of Krings-Ernst Gallery

There is a growing diaspora of Russian-speaking artists of different generations who have left their homelands and are today living and working in Berlin. Many find themselves collaborating with local communities searching for new means of expression.

Russian speaking émigré artists who have arrived in the German capital over the past few years have fled the horrors of war, mobilization or prosecution, and in their adopted home they now live with an uncertain status. Are they able to integrate into the local art communities and create a kind of collective and individual art therapy to exorcise the living ghosts of trauma and a sense of uprootedness, and can they even earn a living?

Many continue to work as before yet respond to their new local context and examine their own personal experiences. How successful this approach is in Germany, and how well can they transplant their origins onto new urban soil is a case of one size does not fits all. Mostly it depends on the vision of each individual artist, as well as those living around them with whom they form their new communities.

Back in 2003 in St Petersburg Chto Delat, an informal collective of artists and leftwing intellectuals first embarked on their artistic activities and ever since then they have worked in a broad variety of new and traditional media including video, installation, billboard, action, academic articles and disputes. The group may now be scattered around the world, but they also have a foothold in Berlin where they have been collaborating with the KOW gallery and periodically stage independent exhibitions in the window of the ‘Emergency Project Room’ in Prenzlauerberg. Here Tsaplya (Olga Egorova) (b. 1968) and/or Dmitry Vilensky (b. 1964) host Mad Tea Parties, which at the last count number over twenty separate events. After registering for free, participants are selected by a lottery, usually ten people who mostly know the hosts, but not the other lucky winners. These guests all gather around a long table and drink tea with an invited Master of Ceremonies who moderates the event.

One former tea party dedicated to a necrorealistic analysis of time and heavy metal was called ‘Killing time with the dead: a heavy metal tea party with Max Evstropov’ (b. 1979). Before that was ‘Fabulations of Exhaustion’ with MC Cau Silva (b. 1990), on ‘politics of refusal as a reclaiming tool for radical imagination’.

The latest edition to take place, called ‘Zu Hause’ (‘At Home’) was part group therapy session and part board game, run by artist Katya Craftsova (b. 1974). Members of the audience, all trying to find their own way in Berlin, took it in turns to share harrowing stories about the ups and downs of settling in the city. To rent an apartment or a room? Couchsurfing. Having a place to stay. MC asked everyone: “What do you call home now?”. After sharing their real stories, everyone was asked to participate in a game consisting of several decks of cards like in Monopoly. Guests had to draw three cards from a pack with which to define themselves, such as ‘Sex worker’, ‘three kids’ and ‘has a cat’, or ‘blue card’ (i.e. high-income expat with temporary residence permit), ‘has a dog’ and ‘homosexual’.

Then they had to pick chance cards from the pack that may bring them money, or one of the necessary documents to stay in the country, or on the other hand that might take away from what they already have. Just like in real life, these bonuses do not guarantee a victory: no matter how high is your income and how flawless are your documents, you can still be rejected by the landlord for a random reason such as ‘male only’ or ‘no pets’. The aim of the game is to secure a place in which to live, whether in a tree house (low comfort score, no documents needed, cannot stay with dogs) or a 3-bedroom apartment (the highest score, you need five or six approvals and a lot of money). When there are no cards left and some have finally won their desired square meters, the score is calculated. ‘I got a two-room flat in Koepenik with a one-year contract, not bad!’ The game is a thought-provoking work of art by Craftsova which is essentially a scathing social snapshot of the era.

ZIP group (Stepan and Vasily Subbotin, born in 1987 and 1991, respectively, and Evgeny Rimkevich, b. 1987) have always seen social cooperation as a means of artistic expression. Their name comes from a disused factory in their hometown of Krasnodar and the collective embodies both the constructivist legacy and a free communal spirit. ZIP’s major achievements are not only exhibitions and art projects, but the Typographia art centre (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) and the KISI contemporary art institute, although after February 2022 the institute closed down and the art centre now exists as a networking platform for creatives in exile.

In 2023 and 2024 ZIP took part in Polidrom, a communication and collaboration project in Magdeburg, conceived and launched by artists and curators Rena Rädle (b. 1970) and Vladan Jeremić (b. 1975). Polidrom literally means ‘a place of many ways’ and is centred on the development of a kind of non-place: a wasteland in the Neue Neustadt neighbourhood in Magdeburg.

In an action ZIP carried out together with local kids and youths of mostly Roma origin they marked the space with rope and homemade signs. They started building there in August 2023 using granite kerbstones which had been donated by the city. The idea was to re-use as many materials as possible and also, at all stages, it was paramount to involve local children. They created a bus stop, a monumental refectory style community table, refashioned by ZIP out of an old stage, and suspended platforms made from old cable reels by the craft and design collective KollektivPlusX. Throughout the building process everything was documented by Nihad Nino Pušija (b. 1965), a photographer originally from Sarajevo living in Berlin. The following summer, they added more monumental objects in this space, including two benches with high poles that can even be used as a football goalposts, a sphinx figure with a hideout zone and a watertight roof for the Polidrom bus stop. A mural based on a drawing by British-Roma artist Damian Le Bas (1963-2017) appeared on a wall painted by Christoph Ackermann (b. 1979) and some of the locals. There was an opening celebration for all those who had taken part, and Damian Le Bas’s widow, artist Delaine Le Bas (b. 1965) gave a poetry performance.

Another project which has recently been organised by ZIP is ‘Klingt Baum’ (Sounds Tree), a collaboration with Boris Pospelov and his Kitchen-On-the-Run initiative. Pospelov prepares food in a portable kitchen and feeds people at protest rallies and other events free of charge. ‘Klingt Baum’ took place in Nettelbeckplatz in Wedding, a mixed district of Berlin with many different emigree communities. Participants gathered in a pedestrian square with a giant tree. There was a stage with an open mic where people sang songs, manifested something or read poetry.

Food and drink are commonly used as a means for social art. Vita Buivid (b. 1964), best known for her photographic work who is currently living and working in the Netherlands, recently visited Berlin to enact what is an ongoing discussion project. Different eminent philosophers were assigned alcoholic drinks and cocktails which are mixed depending on the ideas that the person present at the discussion puts forward after which they must drink whatever he or she has verbally concocted.

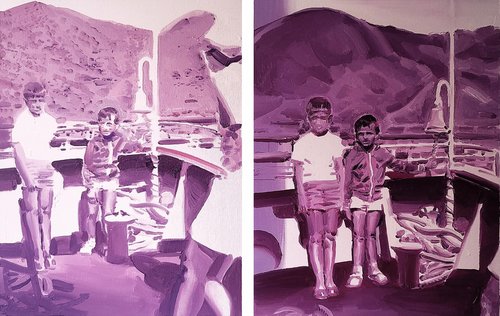

Originally from Nizhny Tagil Vladimir Seleznev (b. 1973) who today is living in Hamburg has found a different path. In November he opened a solo exhibition in the Krings-Ernst-Galerie in Cologne, in which, among other things, he is presenting ‘Metropolis’, a multi-faceted project focussed on urban architecture. Since 2009 there have been local ‘Metropolis’ installations in several cities throughout Russia - notably St. Petersburg (2012), Kazan (2013), Moscow (2022 and 2024). In Cologne he met with local architects to create a list of the most frequently discussed buildings in the city, then locals from the community collected rubbish from the streets. The resulting exhibition is a double portrait of the city by day and night. With the lights on, there is a 3D urban plan made out of debris, followed by a series of paintings made on old paper. With the lights off, the mundane disappears and a miniature cityscape glows with acid green, retro-futuristic, a stylized map on the wall like a techno club logo.

Surveying all these activities one is left with the impression that community-driven, interaction-oriented art is now flourishing throughout the Russian-speaking scene. Something which is counter-intuitive, because in the end as new immigrants they need to invest their time and energies into the problems of settlement, paying for a roof over their heads and negotiating the complex bureaucracy in a foreign language. Most of their community driven projects are realized by using individual grants which can cover some living expenses and artistic materials. It is tough, but this is in essence what artists do, and existing in this limbo and creating something valuable out of it is what makes them artists. They learn by doing and by building networks and collaborating with people. Gathering the reactions of others and fostering better understanding of local contexts.

Is that not precisely where the anarchistic and left ideas really work? Uniting destitute people irrespective of where they come from. Some projects are more object-oriented than others, and one may question whether some of these projects can even be called art, but in the end they create human warmth, and that is what helps one to survive the cold winter.

Metropolis Cologne. Vladimir Seleznev

Cologne, Germany

8 November 2024 – 21 January 2025