Working It Out on Paper

‘Contour’, dedicated to the art of works on paper is Russia’s newest commercial art fair. Taking place in a hotel carpark in Nizhniy Novgorod, it is a pioneering step in promoting an art market outside the Russian capital and of spotlighting this overlooked medium.

A novel idea by the Garage’s contemporary powerbroker Anton Belov, has led to a new art fair in Russia which specialises in the sale of works on paper (in Russia, this is known as graphic art, denoting works on paper in all media and not just printed material). The fair is even taking place in a garage, the underground car park at the Sheraton Hotel in Nizhni Novgorod, and is opening to a crowd of curious, well-heeled Nizhniy Novgorodians. It’s something of a coup. Several big Moscow and St Petersburg galleries are participating, crucially bringing a piece of the art establishment to a city which has little existing commercial art infrastructure.

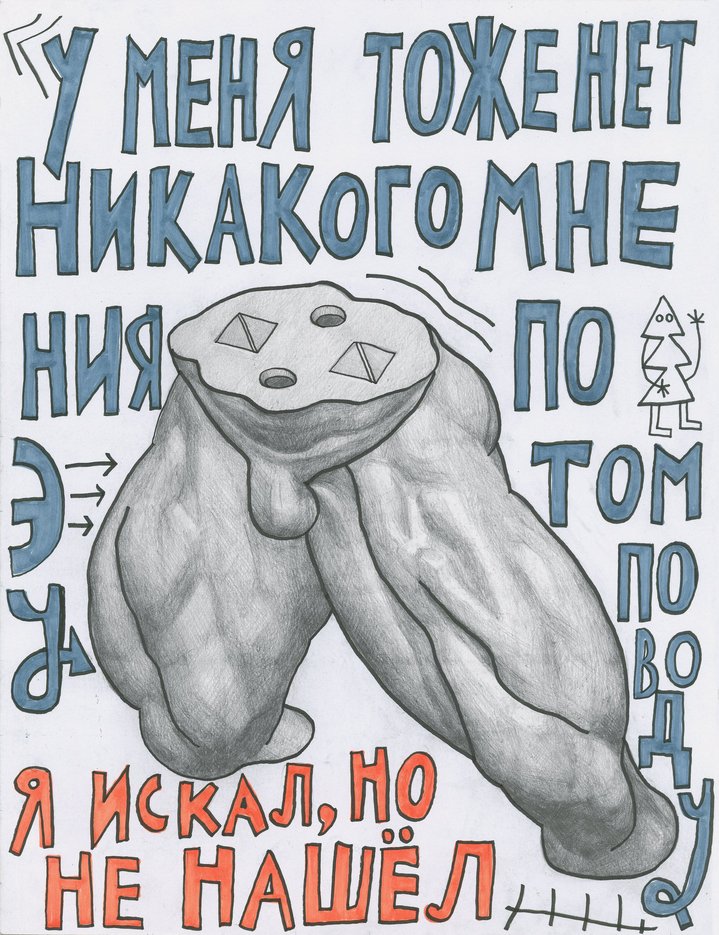

Some of the best ideas start small. On a fairly modest scale, prices at the fair start as low as 5,000 roubles for contemporary prints (approx. 57 Euros) and it is focussed on less established artists, and new, young collectors, as one of the exhibitors from Moscow, Artzip’s Olga Popova concurred, their collectors who buy online are mainly those under forty. There are local artists represented and today Nizhniy Novgorod is best known for its street art, in an interesting parallel with graffiti inspired art gallerist Elvira Tarnogradskaya is showing works on paper by Moscow streetwave artists Kirill Kto (b.1984), Igor Ponosov (b.1980) and Ivan Simonov (b.1991).

From the 1960s onwards, a new tradition of Russian works on paper starts with the Sretensky Boulevard artists, in particular Ilya Kabakov (b.1933), Erik Bulatov (b.1933), Oleg Vasiliev (1931–2013), and Viktor Pivovarov (b.1937). They became giant pioneers in this field, their art is inventive, conceptual, figurative, often with a deep irony, and they are all brilliant draughtsmen. Crucially, their drawings are not that difficult to source, and they are still affordable. Historically important drawings by Oleg Vasiliev can be picked up at auction for a few thousand euros at most showing that sadly few are buying into this field.

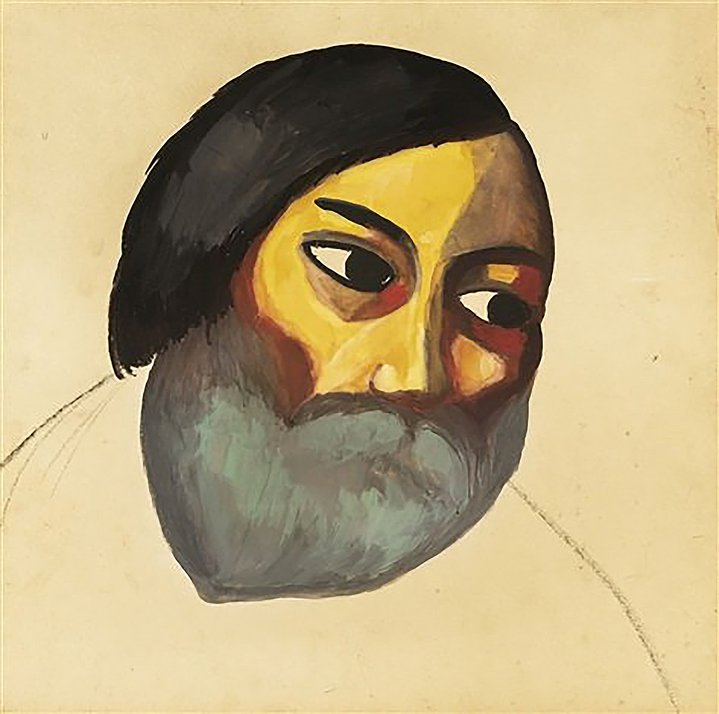

Russia does not have a published, public history in collecting on a smaller, domestic scale. Epic Russia, with its complex dramatic histories past and present is hard to perceive as a nation of art collectors on a small scale. Imperial rulers, merchants and oligarchs have all written the stories of art collecting, and during the Soviet times there was a national obsession with huge canvasses displayed in vast museum spaces. As an art collector no-one is going to notice you for the acquisition of an exquisite sketch by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) on a slightly crumpled scrap of paper, or a drawing by Ilya Kabakov scattered with bluebottles or with a head peeping into the edge of the sheet on what otherwise looks like blank piece of paper. It takes a certain refined taste, that sensibility fit for leaning into the close relationship of lines or marks on paper. During my decades at Sotheby’s, I often heard, and we often talked about how ‘Russians don’t buy works on paper’. It was undoubtedly an oversimplification but, on some level it was true. There were always exceptions, mostly when it came to works by avant-garde or modernist artists working in a figurative vein, like Yuri Annenkov (1889–1974) or Alexander Yakovlev (1887–1938) who excelled in the medium. And Malevich’s ‘Head of a Peasant’, sold in an international auction at Sotheby’s in 2015 not to a Western buyer but a Russian private collector who is particularly fond of this medium. One of the obvious advantages of buying works on paper is their size. For voracious collectors who are literally buying art all the time, walls become quickly crowded.

Interest in collecting works on paper saw better times during the 1980s and 90s. Russian emigrés, or Westerners with a passion for Russian culture buying at auction in London, would fight for a pencil sketch by Ilya Repin (1844–1930) or Natalia Goncharova’s (1888–1962) folk inspired celebratory feasts of colour on paper. There was an understanding of Russia’s historical contribution to the medium throughout the modern era and how it even influenced art in Western Europe. For the modernists, works on paper became closer to fine art than they ever had before, less preparatory workings or informal sketches even if that is what they were. Picasso followed the bandwagon designing for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes intuitively understanding the pioneering step Russians had made in revolutionizing theatre design and taking it mainstream. It did not stop with the modernists. Fifty years later, the Moscow conceptualists had a penchant for documenting everything, for archives of paper, assembling their drawings into albums and in doing so creating a new genre. Their immediate legacy can be seen in artists such as Pavel Pepperstein (b.1966) whose work in oil is a facsimile of his work on paper showing just how enduring illustration has become in Russian contemporary art, more so than the art of any other nation. It is a wonderful quality that is sadly much misunderstood by international collectors of contemporary art who otherwise are quite cosmopolitan in their outlook.

In Russia, artists and museum curators seem to understand the importance of works on paper better than Russia’s private collectors. Today there is a whole generation of young and mid-career Russian artists who are working in this medium, such as Olga Chernysheva (b.1962), Alexander Povzner (b.1976), Katya Muromtseva (b.1990), and Alisa Gorshenina (b.1994), and those for whom even this modest, most intimate of media has catapulted them into the eye of political storms, like Sasha Skochilenko (b.1990) and Yulia Tsvetkova (b.1993) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities). Any budding new collector even with modest means today could assemble a museum quality collection of Russian works on paper and literally chart the history of Russian liberalism in the arts since the millennium.

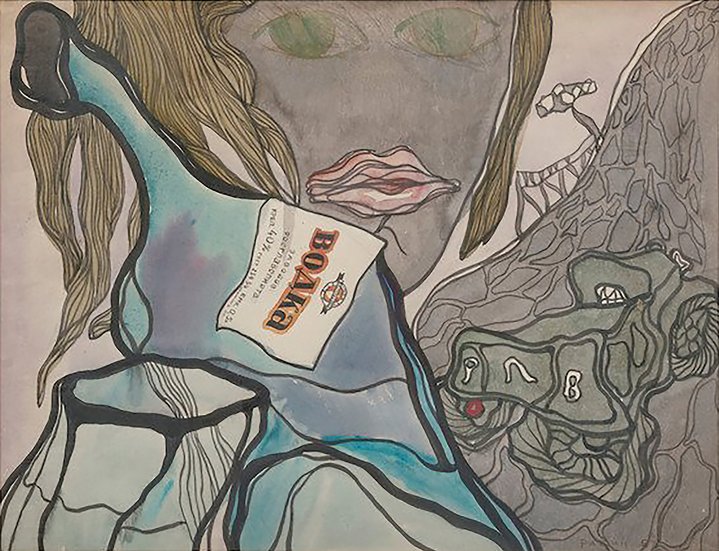

Thanks to the activities of some pioneers in Russia there has been progress made in bringing visibility to the nation’s graphic arts. There is Boris Friedman, whose exceptional private collection of livres d’artistes has been exhibited in museums both in Russia and the West. Private collectors Inna Bazhenova and Alexander Kronik have both been active in this field collecting works on paper by contemporary classic artists. Weisberg’s gouache nudes are now better understood as an independent body of work after the exhibition at In Artibus Foundation in 2022. Oscar Rabin (1928–2018)’s works on paper are in many ways as strong as his works in oil, they tell in dramatic terms the same story of forced emigration, dissidence, and personal resistance. A decade ago, MAMM staged an exhibition of graphic art by Rabin to coincide with the 85th anniversary of his birth, and Kronik recently published his collection of Rabin drawings as a book. At Bonhams this month a 1967 work on paper by the artist fetched nearly 20,000 Euros, a strong price in the medium for a work called ‘Vodka’. Yet although we can raise our glasses and toast such records, they remain outliers in a collecting field whose contours still exist more on paper like a preparatory sketch or unfinished drawing…