What Comes After the House of Cards Fell Down?

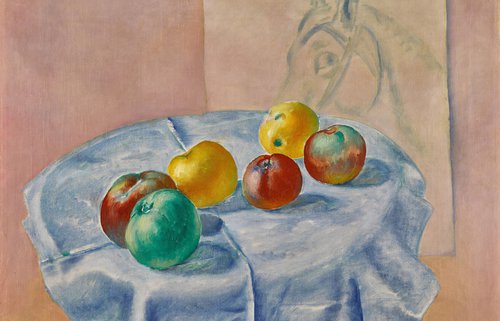

Natalia Nesterova. House of Cards. Private Collection, USA. Courtesy of MacDougall’s

Despite the political and economic turmoil surrounding the Russian art market in the West, 2024 has seen some good prices and a strong taste for traditional values, religious works and themes, as well as continued interest in Soviet Non-conformist art. That said, set against a booming domestic market in Moscow with new auction initiatives there and art fairs growing like mushrooms, it is still in the doldrums.

I feel somewhat lost in this moment in time. Three years have passed since there were dedicated ‘Russian Sales’ in London, which had existed in a similar form since the late 1980s, when descendants of émigré white Russians and celebrities the likes of Slava Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya, and Prince and Princess Michael of Kent gathered in Bond Street to sip champagne while they browsed the Russian Imperial arts on offer, much of which had come directly from families who left Russia after the Revolution. Then the new Russians and oligarchs arrived, collecting tastes changed and they created a booming market until things sank in 2014. A brief and slow recovery ended in 2022 with no auctions for the first time in several decades.

Yet, since 2022, despite lacking a dedicated platform, I will venture to say that sales of Russian art have made a small comeback at the major London houses this year in some very modest shape or form, repackaged with new titles – there is the École de Paris and Other Masters’ at MacDougall’s and ‘Faberge, Imperial and Revolutionary Art’ at Sotheby’s, no such initiatives at Christie’s and Bonhams is focussing on Non-conformist art in Paris where it has continued to offer dedicated sales over the past few years, with more consistency than anyone else.

The Russian sales were never only about Russian art, and in today’s new climate this gives pause for serious thought. It was in the 1980s that the auction houses made a stampede on themed sales – it made good business sense to market works to specific types of buyers from certain geographical or cultural regions. For over three decades the Russian sales in London and New York were filled with artists who were born in many different countries which once formed part of the Russian Empire (sometimes also German, French or British artists who worked in Russia) packaged with an anti-Soviet hinterland which lasted until the end of the 90s, and even later when there was a good market for Soviet art Christie’s rarely ever offered Soviet Realist paintings in their auctions. Since gaining independence in the 1990s at home these countries began asserting their own cultural identities, and engaging with this process was not a priority for the Western auction houses for whom Russian art had become such a huge asset. I recall only one episode some years ago when the Georgian ambassador in London once came to visit me and asked with indignation and frustration why Georgian artists were being offered in Russian sales.

Before the mid 1980s you had to search for Russian art spread across many different auctions – you could find paintings by Ivan Aivazovsky in 19th century European Art sales or by Natalia Goncharova in Modernist and Impressionist art sales – and it was only decorative works of art and icons which had their own dedicated auction catalogues. Today, effectively we have gone back to the 1980s: the most expensive Russian painting sold in London this year was at Bonhams hidden away in a ‘19th Century and British Art Auction’. It is a small grind to have to look for Russian paintings across all the sales, it benefits buyers rather than sellers, because not everyone can keep track of what is being sold.

Yet, I do not think this status quo will continue past the uncertainty and turmoil of these years. If the Russian sales as they were for decades will never come back, they will be replaced with something analogue which will endure because in spite of the economic sanctions and the political turmoil in these years, there is still a good market, large numbers of wealthy people from parts of the post-soviet world who live in the West (those who emigrated and now their children) and in a global art market that is fast cooling down, the big auction houses need to be flexible to catch all and not just selected opportunities, diversity is key to good business sense.

This amounts only to a small piece of positivity in what is still a very bleak context, when in 2022 the international Russian art market fell down like Natalia Nesterova’s ‘House of Cards’, a mere consequence of something unthinkable and far worse than a fallen market: the horrors of war. How and exactly when the house of cards will be built up again is anyone’s guess. For one thing tastes are changing and there is an exodus into religious art, Russian icons, and traditional paintings and works of art that boost a sense of national pride or have some particular historical value. But these tastes are currently reflective of an extreme moment in time, how will they evolve later?

The taste for Russian history was very much in evidence at Sotheby’s this Autumn where three commissioned portraits painted by Zinaida Serebriakova (1884–1967) came up for sale. Dated to 1925 when she was living as an émigré in Paris painting rather stiff portraits of wealthy white Russian émigrés, there were portraits of Prince Felix Yusupov, Princess Irina Felixovna Yusupova and Princess Irina Alexandrovna of Russia which collectively fetched 750,000 Euros, far above what were reasonable expectations. Bonhams star lot and the biggest sale of the year in London was for a historical painting by Vasily Polenov (1844–1927) from his cycle of paintings ‘The Life of Christ’ which sold for 1,4 Million GBP. Auctions of Russian pre-revolutionary art including Fabergé have performed very well this year at both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, and also in New York which has traditionally been a strong base for the trade of Faberge, in part because North American collectors have long had a taste for it.

In November, both Christie´s and Sotheby’s saw strong prices for the sale of Russian and Ukrainian artists in their auctions. The Collection of Romanian-American designer, philanthropist and collector Mica Ertegun included several rare works on paper by Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde artists all of which made strong prices. ‘Rhythme Coloré’ by Sonya Delaunay (1885–1979) a late work created in 1954 albeit with an earlier aesthetic, fetched 100,800 USD, outstripping the prices achieved for prime works by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) and Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880–1930) which nevertheless were in huge demand, with Malevich’s suprematist ‘Magentic Construction’ almost tripling the presale low estimate hammering down at 94,500 USD and ‘Still-life Bouquet with Autumn Leaves’ by Bohomazov sold for 81,900 USD, a world auction record for a work on paper by the artist.

In part due to Brexit which shook the London market up and resulted in more sales on the European continent, over the past few years Sotheby’s has been holding auctions in Cologne. In November a small yet first-rate group of paintings was offered there in a sale of international modern and contemporary art by blue chip non-conformist artists consigned by a private German collector whose parents had acquired them in Moscow in the 1980s. One of the gems of the group was a large scale early canvas by Victor Pivovarov (b. 1937) which sold for 108,000 Euros, double the low estimate given by the experts before the sale (although to my mind a bargain for the lucky new owner as such historical paintings by this artist are extremely rare). There was also an early windows painting by Ivan Chuikov (1935–2020), ‘Window Áfter Aivazovsky’, which sold for 72,000 Euros, a series which in many ways best defines the artist, and a fantastical painting by Leonid Purygin (1951–1995) inscribed in Russian ‘Democracy and Glasnost, I am for Gorbachev’. Curiously, despite the strong bidding on these paintings, the major disappointment was a large scale painting Ólga Nikolaevna Kazmina, ‘Whose Fly is This?’ by Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) a programmatic piece on masonite evocative of his famous Communal Kitchen installation which did not sell.

Those of us in the West who have tried to keep an eye on developments in the domestic art market within Russia throughout the past few years, see a very different picture forming there where sales have been booming. Domestic Russian auction houses, such as Vladey have continued to produce numerous Russian art sales at a fast pace, and there are newcomers, like AuctiON, a new auction house founded by Olga Popova that staged its first ever auction this Autumn in which it offered for sale works by Soviet non-conformist and Russian contemporary artists. There are also new domestic contemporary art fairs with anecdotes of paintings flying off the walls. One downside to the domestic market in Russia is the lack of blue-chip masterpieces to be offered within public auctions with the best works mostly sold privately, leaving those trying to survey the size and scope of the market open only to wild guesses. And a study of the published auction results in Moscow leaves one with less positive impressions because traditionally the sell through rates of public auctions there are less than impressive, often only half of the lots sell. Good sell through rates are indicative of a mature market and an important sign of stability to collectors, the absence of these creates a dampening effect. An exception this Autumn was a painting by Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) ‘Child with Balloon’ (1988) which was sold by Vladey for a near record price of 575,000 Euros (the world auction record was set in 2021 at Sotheby’s for ‘Boy With Balloons’ which sold for 671,500 Euros).

Lack of transparency on the Russian domestic market means that often such results come with many questions, is it a genuine price? Whether this is fair or not, until there is more transparency and more genuine competition on the domestic auction market, it will always remain somewhat beholden by what goes on in the West even if the prices in London are not an accurate reflection of what happens on the ground in Russia, which is where the market really resides. For better or for worse.