Thriving in Isolation: How Sanctions Are Boosting the Domestic Russian Art Market

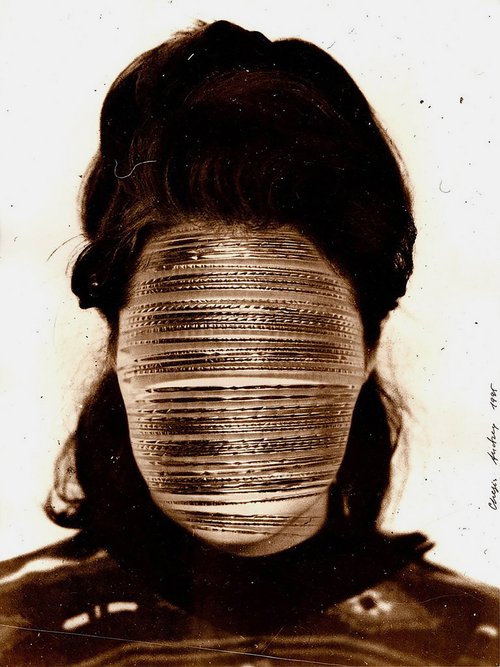

Oleg Tselkov. Toilets for men, 2013. Courtesy of Vladey

International sanctions seem to be having a positive effect on the domestic Russian art market, where sales are stronger than ever. At the opening of Moscow’s |catalog| art fair many Russian art dealers commented on this paradox.

Just one month after Cosmoscow, where most galleries reported strong sales despite its new and remote location in the Moscow suburbs, Russian art dealers have gathered once again for |catalog| art fair. A relative newcomer to the roster of large-scale art events in Moscow and now in its third edition, this twice annual fair was initially founded by dealers looking for a more democratic approach when compared with other art fairs around the world. All the booths are the same size and allocated by a lottery. With fifty-five galleries taking part and in a central location, it has quickly become a strong rival to Cosmoscow although most of the major galleries from Moscow and St Petersburg take part in both fairs.

With limited space in the historic former printing house in the centre of Moscow, demand for stands at |catalog| far outstripped supply. According to Alexander Sharov, the fair’s co-founder and owner of 11.12 Gallery, there was a waiting list of around thirty galleries, even some who took part in previous editions and who were not accepted this time. Prices ranged from a modest 70,000 roubles (approximately 630 Euros) for ‘Alchemical Comics’ by Alexandra Demidova (b. 1984) – humorous watercolours on vintage wallpaper in the style of medieval miniatures, offered by the Totibadze gallery, to 100,000 Euros for a major painting by Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) at Vladey auction’s booth, apparently a modest price as just one week before another of the artist’s works hammered down for an impressive 575,000 Euros at the same auction in Moscow, sold to Russian rapper Timati. For this third edition of the fair, the organisers introduced a new rule that each gallery must show at least one emerging artist in its booth, but interest in new names is growing, as the strong results of September’s Blazar fair showed.

On the eve of |catalog|’s opening, the organisers hosted a dinner for collectors and afterwards guests were free to wander around the aisles at the fair, while |catalog| staff noted down their purchase requests and placed red dots on the walls. At the press conference the next morning, organisers reported that seventy sales had been made the night before. The market is clearly booming. Dealers are unanimous in attributing it to one reason alone: the financial isolation of Russia.

Mikhail Krokin, whose gallery, founded over 30 years ago is one of the oldest in the country, told Art Focus Now that the market is buoyant because of the large number of roubles swirling around in it. As the Russian national currency has always been seen as unstable, collectors were used to paying for art in Dollars and Euros. Now many people do not have easy access to foreign currency, but they have a lot of roubles in their wallets and bank accounts. Krokin has seen changes in both supply and demand in the market. He is concerned by what he sees as the deteriorating quality of the art on offer. “Much contemporary art is becoming more like decorative art but I believe our mission is to educate the taste of the collector. At Krokin Gallery, every solo exhibition conveys some philosophical idea and I do not like it when an otherwise good artist starts making something colourful and decorative just to satisfy the public’s taste”. He added that after the armed conflict with Ukraine broke out, some buyers started looking for ‘patriotic’ artworks for their offices. He has seen two new types of collectors emerge in the past two years. “First, there are those people who now have a smaller budget but still want to enjoy collecting. They ask for more affordable works by their favourite artists such as drawings, silkscreens, and maybe a sketch or a small painting”. There are other collectors for whom budget is no issue and they come to the gallery asking for the best works by a particular artist. “Some moved back to Russia because they felt uncomfortable in Riga, London or Paris, even though they have legal residency status there. They are asked a lot of provocative questions these days, or they have problems doing business because they are Russians,” says Krokin. When they return to Moscow “they want to renovate their houses and apartments which lay dormant for many years. Often they already had very decent collections of art from the 1990s and 2000s on their walls, but they want to update them to keep up with the times”. The gem in Krokin’s booth is a work on paper by charismatic artist and former naval officer Alexander Ponomarev (b. 1957), a view of his recent installation ‘Uroboros’ in Egypt, drawn on an old Soviet map, with a price tag of 30,000 Euros. Paintings by Konstantin Batynkov (b. 1959), laconic winter landscapes with a surreal twist, are being offered for as little as 6,000–8,000 Euros.

Another veteran of the Moscow art scene, Vera Pogodina, has also noticed the excitement at the top end of the market. “All the money that wealthy Russians used to spend in the Côte d'Azur is now here. Although people generally prefer to invest in real estate, some are now looking at art. No-one cared about prices at Cosmoscow and I sold everything on my stand. I was euphoric!” Paradoxically, however, sales at the lower end of the market have slowed down, believes Pogodina. A week before |catalog| opened, she set up her annual best-selling exhibition of affordable art called ‘Postcards from Artists’, a staple of the Moscow art scene for many years, where art lovers with a small budget buy New Year gifts. (Since the Soviet times, Russians exchange gifts on New Year’s Eve, and not at Orthodox Christmas). This year, Pogodina offered artworks starting at a modest 6,000 roubles (approximately 55 Euros) in her exhibition. “This price range is aimed at the middle classes, which hardly exist nowadays. We had a lot of visitors at the opening, but not so many buyers. The clients who used to buy before were mostly doctors, journalists and the like, but this year they did not come. A few super-rich collectors did come, however, and haggled over pieces worth 20,000 roubles (180 Euros).” Pogodina’s exquisitely curated stand at |catalog| is dedicated to sea-themed art: from drawings by Julia Kerner (b. 1966) at 150,000 roubles (1350 Euros) to a painting by Vinogradov & Dubossarsky at 5,000,000 roubles (45,000 Euros).

Elvira Tarnogradskaya, owner of the Syntax gallery, is offering a selection of text-based works by Kirill Lebedev (Kto) (b. 1984), Ivan Simonov (b. 1991) and Vikenty Nilin (b. 1971) at her booth, priced from 1,200 to 6,000 Euros each. She told Art Focus Now that with the highly volatile rouble and limited opportunities to transfer money abroad, some people are buying art as an investment. As a result, there is a growing interest in relatively expensive works, with prices starting at 50,000 Euros. “With the difficulties of purchasing art on the international market outside Russia and the volatility of the rouble, there is now a huge demand for expensive works of art by Russian artists,” she observes. Tarnogradskaya agrees with Pogodina that sales are slowing down for the bottom end of the market, works priced below 200,000 roubles (1800 Euros). “The poor are getting poorer and the rich are getting richer,” she observes. Tarnogradskaya has also noticed a decline in sales of conceptual art which challenges viewers. “The older generation of collectors, sophisticated intellectuals, seem to be stepping back, and newcomers have become much more active. As a result, bright, colourful works are selling better,” she says. The new collectors are opting for more commercial media such as painting and drawing. Still, she admits that some collectors swim against the tide, looking for new names and buying entire exhibitions or large installations in bulk. But this is not happening as often as it used to, she says. Tarnogradskaya, who is based between Moscow and Dubai, says that Russian expats currently living abroad do not feel rooted in their new homes, always feeling that they might move again, so they do not buy large and expensive artworks: they prefer smaller pieces priced under 10,000 Euros.

Alexander Sharov, owner of 11.12 Gallery and one of the co-founders of |catalog|, agrees that art buyers now prefer colourful, positive artworks with uplifting themes that they can live with. He told Art Focus Now: “As a gallery we used to focus on deep, meaningful, sometimes quite challenging art, but we have found that these things are not popular at all now. People tend to stay away from that kind of work”. Sharov admits that the gallery’s sales are fluctuating wildly “very active for a bit and then slow”. Nevertheless, the market is lively, he says, as the number of visitors to art fairs and his gallery is not going down. He switched to pricing art in roubles 4–5 years ago and is gradually increasing the figures on his price list to keep up with inflation. His booth is packed with objects and paintings by several artists on the gallery’s roster, most however by Vassily Slonov (b. 1969). This artist from Krasnoyarsk was recently sentenced to a year’s corrective labour for a work of art he created from a children’s toy covered with prison tattoos, which the court deemed ‘extremist symbols’. The gallery is offering his tongue-in-cheek objects, including many similar works, for 150,000–450,000 (1350–4000 Euros).

Sergey Popov, founder of pop/off/art gallery, says the market has been growing since the pandemic. “The growth started in autumn 2020 and has not stopped since then. I can see it in the financial results of my gallery and in the fact that many new galleries are opening in Moscow. Demand is growing and the number of young collectors is increasing.” Popov told Art Focus Now. “The main reason for this is the huge amount of available money locked up in the country. Previously people preferred to invest their money abroad,” he said. Popov pointed out that the investment boom is not limited to the art business. “The investment market has been booming over the past few years.” But crucial he adds is that the infrastructure of the art market was already in place in Russia when the money started pouring in. “As a gallery, we were ready to grow,” he says. According to Popov, the turnover of his gallery has recently been growing by 50% a year. Collectors are also showing more interest in non-traditional media. “We now have several clients who regularly buy installations and very odd objects.” One major downside is that the situation is taking its toll on artists, whether they stay in the country or emigrate. “Russian artists are now being hunted down like a Wandering Jew,” he says. “They cannot exhibit their work in Russia because of censorship and blacklists, or abroad, where they are ‘cancelled’ as Russians, even if they emigrated decades ago.” Popov notes that self-censorship also has a negative effect on Russian creatives inside the country, while emigrating artists, especially young ones, often stop producing art because of the frustration caused by relocation. “This will lead to a deformation of Russian contemporary art,” he believes. “The degradation is not very obvious yet, but it is already beginning to show on the fringes.” The pop/off/art booth features a diverse selection of international artists in various media, including minimalist sculptures by well-known Russian emigre artist Andrei Krasulin (b. 1934), now based in Berlin, for 3,500–25,000 Euros, and semi-abstract paintings by Greek artist Despina Flessa (b. 1986) for 3,000–8,000 Euros each.

Sergey Popov’s wife, Olga Popova, owner of online gallery Artzip, says there is a lot of activity on the secondary market now. There is a generational shift: “Some of start selling because they have reached a certain age. Others die and their heirs start selling because they have different tastes or want to change the focus of a collection they inherited.” She has even opened an auction house, following in the footsteps of Vladimir Ovcharenko, a veteran Moscow gallerist who launched Vladey auction house eleven years ago. “We were doing so much business on the secondary market that we decided to go public,” says Popova. The new AukziON will hold monthly sales in a hybrid offline/online format. The first due to take place on 12th December, called, ‘I Buy, Therefore I Exist’ will feature rare early works by Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013), Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) and Valery Gerlovin (b. 1945), as well as more emerging art.

Ekatherina Iragui, whose gallery has branches in both Moscow and Paris, says she misses the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the past in the Russian capital, as many of the expats who were regulars at her gallery have left the country. At her booth, a meditative lakeside landscape by Olga Chernysheva (b. 1962), an established artist with an impressive international exhibition record, is offered for 14,200 Euros, while intricate drawings by the late Nikita Alexeev (1953–2021) are priced at 1,500–2,200 Euros each. Iragui disagrees with other dealers about the changing tastes of collectors. She believes that in today’s bewildering reality, more and more people are developing an interest in deep, conceptual art, “contemporary philosophy in visual form that seeks to explain the inexplicable”. She notes that relations between art dealers have changed a lot since she opened her gallery in Moscow thirteen years ago. The market is still very small by Western standards, but the general mood has become much friendlier, she says. “Back then, gallerists would barely say hello to each other. Now it’s different, there’s a real sense of community.” Iragui, who teaches international art business strategies at the British Higher School of Design in Moscow, says she urges all her students to open galleries. “I tell them: the more of us out here, the better for everyone.”

|catalog|

Sytin’s Print Shop

Moscow, Russia

6–8 December, 2024

I Buy, Therefore I Exist

Moscow, Russia

12 December, 2024