Francisco Infante. Infinity Spiral, 1963. Tempera on card. Courtesy of Bonhams

The New Evergreen Art of the Underground

The Russian art market has endured two major crises in as many decades, when Russian Contemporary and Soviet non-conformist art was ghosted by the market overnight. Yet amid an even greater crisis today, Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr in Paris has kept the flame alive with an auction dedicated to Russia’s non-conformist art.

It is often said that the greatest refuge in a troubled market are the classics. Safe artists who have performed solidly over decades, are preferable to lesser established names. There was a clear return to 19th century Russian classical art after the economic crisis of 2008; and at the top of the market big household names, especially the modernists, were still in demand, and even sometimes brought exceptional results. Yet, as the saying goes, during both those crises the demand for Russian contemporary and non-conformist art fell so far that dedicated auctions in London themselves went under the axe.

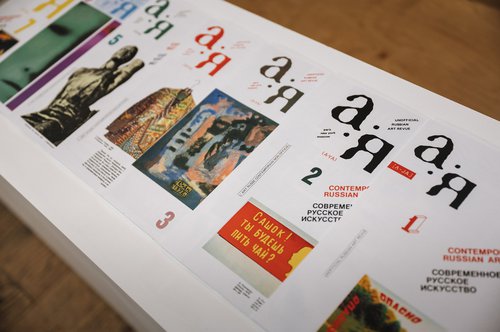

But these are unprecedented times and all Russian art sales in London have been cancelled indefinitely. As one seasoned collector put it recently, we are seeing a return to the 1980s when Russian art was sold across several categories. At that time the avant-garde was sold with Modern and Impressionist European paintings, and 19th century Russian paintings were sold in the context of 19th century European sales. There was no contemporary Russian art sold at all in the main London auction houses then, nor later, when dedicated Russian sales were evocative of pre-Revolutionary Russia.

In this current crisis, just how deeply the entire Russian art market today has been cut and shaped by the financial sanctions goes hand in hand with who can trade on the Western market itself. There are serious, practical hurdles to overcome for art professionals in Western Europe and North America, whether auction houses or private dealers. Registering to participate in an auction of Russian art now raises a barrage of uncomfortable and intrusive questions. Then, there is the issue of cancel culture and Russian-Western political relations.

Into this troubled context, Bonhams’ auction in Paris was the first (and only) dedicated Russian sale to take place in Western Europe this year, an auction not of reliable old classics but of Russian underground art. In London Bonhams was not the first-choice destination for sellers of Russian art, but they had recently been making efforts to move into the lower stakes market of non-conformist art. They addressed fears of cancel culture by referring to the sale title as ‘non-Conformist art’ (although if you were searching for ‘Russian art’ on their website, you might not have found it).

The current climate in Western Europe is exceptionally hostile to Russian artistic and cultural initiatives, commercial or otherwise, yet if I were to organise a Russian art auction at this time it might just have been the non-conformists I would have turned to. In times of crisis, where the whole market has been scrapped after decades of growth, and there is hostility between people brewing under the surface, do we not look for humane values which run deeper, that can somehow find their way through both sides of what is a bitter ideological divide?

Like today’s contemporary artists leaving Russia en masse to Tbilisi, Tel Aviv, London, or Paris, an exodus which started long before the events of February this year, the non-conformists were anti-regime. The days of their activism in pursuing their own beliefs are long over and the conditions they endured were exceptionally hard: to make formalist art where formalism itself was forbidden is hard for younger generations today to fully understand. These were artists who were persecuted, at worst sent to mental asylums or prison, who were forced to emigrate, or who wanted to leave the Soviet Union because they had enough. However, remarkably today, on the spectrum between liberalism and conservativism, their art seems to fit at either end. Formalism in Russia is no longer such a bad guy; although there are still sensitivities around the use of religious imagery in art, something which even Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) experienced at the beginning of the 20th century.

Is there not some growing sense that this underground art might be able to unite taste across the divide and in doing so, in broad brush strokes, define something valuable about the times we live in now? In the West we can appreciate the troubled predicament these artists faced; we feel empathy. But more important than this for the art itself, until now we have been too used to seeing underground art more as expressions of dissidence and resistance rather than fine art. Now as the passing of time inevitably takes this art out of its original context, we can see its universal values: Oscar Rabin’s (1928–2018) forget-me-nots in a dark landscape can be about love and loss rather than a eulogy for his lost homeland under an autocratic regime. In Russia you can hail Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) a great genius now because you can quietly project what you want onto his grotesque vision, where once he was thrown out of the Repin Academy of Arts for ideological reasons.

Whether because of this or other social forces at play, at a time when over the past decade contemporary art has been gradually dismantled inside Russia (the day before the auction the 9th Biennale of Contemporary Art was cancelled with no warning sparking comments in the press it marked the end of contemporary art in Russia) it seems that there has been among private collectors both inside Russia and abroad a growing taste for the ‘rebel artists’ of the past. And as the grip tightened on artistic freedoms in Russia, over the past few years this part of the market showed a growth spurt both at auctions in the West and in Russia. Compared with the daring performances and actions of Russia’s contemporary artists today, non-conformist art now looks genteel or tame, the edge it once had softened.

Through the eyes of the dealers and collectors the Bonhams sale represented a cache of well-priced artwork of the era, but everyone agreed that the collection lacked top lots. It was classic middle market fare. They had chosen two paintings to lead the sale, a 1960s era still-life by Vladimir Weisberg (1924–1985), and a brightly coloured ‘Chagallian’ Monastery by Vasily Sitnikov (1915–1987). The artist produced many of these works during the Soviet times, which were particularly popular with foreigners who visited Russia. The punchy pre-sale estimates for the Weisberg scared off bidders and the Sitnikov needed to be viewed in person, so bidders shied away despite its reasonable estimates. The auction was far from overloaded, it was a pared back, a minimal selection of top names representing a multitude of different styles and movements, a good strategy under the circumstances.

Oscar Rabin’s 1957 ‘Bouquet dans un Paysage à Lianozovo’, once in the collection of Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016), was the most expensive lot of the sale and went to one bidder, hammering down at just over 60,000 Euros, not a bad result for a painting which cannot be numbered among his best works. Despite a strong market for works by Oleg Tselkov, his late 80s ‘Deux Têtes Vertes’ struggled to sell. Those who did attend the sale were treated to an eyeful of works by Vasily Sitnikov and his workshop, many of which were unframed in folders and a pleasure to leaf through. A charismatic artist with a few slavish followers, some of the works were signed by his pupils and could easily have been mistaken for his work. An exceptional female portrait by the artist which had been exhibited at the famous Biennale of Dissent in Venice in 1977, was described defensively as a ‘workshop’ painting and priced at 1,000 Euros, eventually sold for 16,000 Euros after heated bidding in the room and online. There was also a Steinberg moment in the auction, with three paintings by Eduard Steinberg (1937–2012) making it into the top ten results for the sale, topped by ‘Composition. Novembre, 1978’. Prices for the artist were not far short of the results achieved in the fabled, record-breaking Bar-Gera sale at Sotheby’s six years ago, perhaps now beefed up by the ten-year anniversary of the artist’s passing in 2012.

All in all, the auction was an exceptionally modest and gentle exercise, in the same week that over a billion dollars of art was sold in New York from the Paul Allen collection at Christie’s making it the biggest auction in history. Yet it was hard not to go away with the feeling that something important had happened in Paris. Markets need to be fed to exist through good times and bad, and perhaps we have finally reached the moment where Russia’s non-conformist artists are no longer shedding their leaves in Winter, these new evergreen artists of the underground.