The Fragility of Legacy: Art Collectors, Power, and the Problem of Permanence

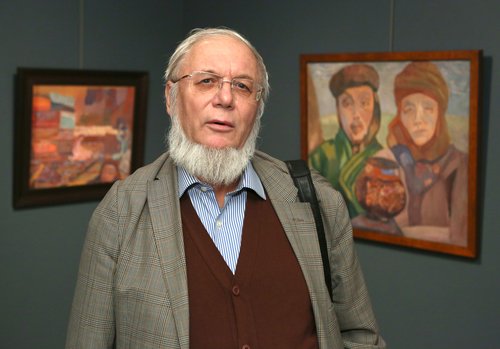

Valery Dudakov at the opening of 'Russian Symbolism: From Vrubel to Larionov' exhibition. Courtesy of Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum

With recent controversies surrounding the fate of the legendary Dudakov–Kashuro collection and in a period that has also seen the temporary freeze of Petr Aven’s art collection in the UK and the shuttering of Alexey Ananiev’s ‘Institute of Russian Realist Art’ in Moscow how can mega collectors realistically plan for, and safeguard, their long-term visions? The noble ambitions of donating works to the state or founding a private museum for the benefit of future generations remain acutely exposed to political turbulence, shifting values, and the inevitable infirmities of age.

Art collectors often remind us that they are not owners of their art, rather guardians. The million-dollar question of what the greatest art collectors of our era plan to do with their collection is a matter of interest, not only to dealers and auction houses who make it their business to find this out, but also to the public at large. World class museums have evolved out of private collections like the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow founded by Pavel Tretyakov in the middle of the 19th century and the Tate gallery in London whose collection was formed from a donation by sugar magnate Henry Tate in 1897.

Today, outside the Middle East, it is not royalty that is assembling the museums of the future, it is mostly captains of industry and if you want to build your own vision, the enormous costs involved mean that being a billionaire is a prerequisite. Yet even that does not guarantee success. Just take the example of Russian entrepreneur and banker, Petr Aven, whose vast collection of mostly Russian and some Latvian art is currently the subject of an asset freeze in his home outside London. In Riga, there sits an empty building opposite the Latvian National Museum of Art which Aven purchased back in 2021 ostensibly to partly house his collection and act as a platform for temporary exhibitions. It was slated to open in 2025, to fulfil a long-held dream of creating a cultural space in his family’s ancestral country, yet currently it is on indefinite hold. When Aven set up home in the West two decades ago he must have imagined the art collection would be safer there, rather than in a country where the famous art collections of Shchukin and Morozov, which are the pearls of the Hermitage and the Pushkin Museum were appropriated by the State.

Can any of us, billionaire collector or otherwise safeguard our future visions in a world which is fast changing around us and in which politics can run roughshod over an otherwise well-tended plot of cultural history making?

Moscow-born Valery Dudakov, who recently turned eighty, is one of the last remaining collectors from the Soviet era who, over decades, has amassed an exceptional trove of Symbolist and Modern Russian art, not to mention, masterpieces by the non-conformists. It was close friendships with all the leading underground artists in the 1970s that formed his sensibilities as an art lover and collector, eventually finding in collector Yakov Rubinstein (1900–1983) a mentor who honed his skills in acquiring art. I recall my own first encounters with Valery Dudakov nearly three decades years ago in the heady 1990s when I was working as a young expert at Sotheby’s and I am still thankful for his generosity at the time in helping me with difficult questions around art authentication. Years later, when the Russian art market transformed from what he would have seen as an ecosystem driven by connoisseurship to one where the ill-informed tastes of new Russian collectors drove it often senselessly from one record to the next, he was outspokenly critical of the London auctions, and I understood this.

Back in 2010 in an interview published in the Tretyakov Gallery magazine, Valery Dudakov had talked openly about his desire to see his collection in a Russian state museum, and at the time he was exploring the idea of the Treytakov Gallery itself. However, as is customary, guarantees could not be given about housing the collection permanently on its walls and discussions later ended. Then an idea surfaced about finding a new home for the collection in Saratov to be housed in a projected building dedicated to Symbolist Art. At the heart of his collection lies a group of masterpieces by the Blue Rose painters, one of the earliest areas of Dudakov’s collecting interest and Saratov itself held particular resonance, as it was the birthplace of several key figures associated with the movement, including Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910) and Victor Borisov-Musatov (1870–1905). Discussions with local authorities in Saratov continued for more than a decade; however, the construction of the promised purpose-built museum was repeatedly postponed.

More recently, this spring, a decision was taken to transfer the core of the collection to the Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum, where highlights are currently on view in the exhibition ‘Russian Symbolism: From Vrubel to Larionov’. Controversy has since emerged regarding the collection’s legal status, with suggestions that the works have not been formally donated to the museum but are instead on loan as the property of a private foundation. Regardless of the precise legal arrangement, the collector’s son, Konstantin Dudakov Kashuro, has expressed concern that his father’s long-standing wish to see the collection permanently displayed within a Russian state museum – one that he and other close family members share - may not ultimately be honoured. He has therefore initiated legal proceedings in an effort to safeguard what he regards as his father’s true intentions; at the time of publication, however, Valery Dudakov had not been reachable on this matter, leaving key questions unanswered.

Even with robust legal frameworks in place, however, the fate of major collections is rarely guaranteed. In the USA, the history of the Barnes Foundation offers a cautionary example. Founded by Albert C. Barnes, the son of a butcher who became an immensely wealthy entrepreneur, the collection was conceived as an educational tool for the public. Barnes established a foundation governed by strict stipulations: prohibiting reproductions, social events, loans, or the relocation of the works. Yet many of these conditions have since been violated, including his express wish that the collection never be moved.

Closer to home, in the early 1990s, the reclusive art historian and collector Nikolai Khardzhiev (1903–1996) took matters into his own hands, making plans to emigrate to Amsterdam with his extraordinary archive that comprised some 1,350 rare works and documents relating to the Russian avant-garde, alongside paintings and works on paper by artists such as Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), El Lissitzky (1890–1941), and Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953). These intentions left the elderly Khardzhiev acutely vulnerable to a series of attempts to appropriate parts of his collection, in a sequence of events that reads like a Shakespearean drama with a tragic conclusion. While some works later surfaced at auction in the West, much of what remained in his possession was placed into a foundation following his death in 1996. In subsequent years, the foundation reached an agreement with the State Archive of the Russian Federation (RGALI) to administer what remained of Khardzhiev’s archive, bringing a measure of closure to what had become a protracted, chaotic, and deeply controversial legacy. In 2017, when a quarter century embargo Khardzhiev had set on the publication and public access of the archive had expired, In Artibus published the first book about it in partnership with RGALI creating new scholarly understandings about the history of the Russian Avant-garde.

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the assembling of major art collections in Russia took place against a backdrop without parallel in modern times – both extraordinary and, in many respects, humbling. Some of the country’s most important twentieth-century collectors risked their careers and reputations, or at the very least engaged in activities regarded as antisocial or clandestine, in order to build their collections. At times the atmosphere was relatively permissive; at others it grew markedly tense, depending on the prevailing political climate. Collecting art that ran counter to official doctrine or existed outside state institutions carried a distinct frisson of the forbidden. It also allowed collectors to surround themselves with a rare form of personal freedom—one scarcely available elsewhere.

This protective, almost talismanic quality of a collection, worn like a magic coat, created an emotional investment in art that is difficult to fully grasp today. Such collections, like that put together by Valery Dudakov, often covered the walls of modest apartments from floor to ceiling, enveloping the collector and their immediate family in a self-contained, distinctive world. Yet time exerts its pressure on everyone. How, under such circumstances, could a collector ever detach themselves from their art sufficiently to plan a legacy?

The concept of a museum dedicated to Symbolist art in Russia emerged alongside other private initiatives where collectors have founded art institutions focused on specific artistic movements – most notably the Institute of Russian Realist Art and the Museum of Russian Impressionism, both established in Moscow during the 2010s. These projects demonstrated the true breadth and depth of Russian art history, cutting through previously politicised curatorial frameworks and reflecting the intellectual passions of their founders. Noble in intent and impeccably realised, both of these initiatives have nevertheless met with unhappy outcomes. Alexey Ananiev saw his collection seized by the Russian state, while Boris Mints was forced to leave Russia only a few years after his museum opened and although his collection remains central to the museum’s holdings, the centre of power has unmistakably shifted.

Russian Symbolism: From Vrubel to Larionov

Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia

4 December 2025 – 29 March 2026