Artistic power-couples: 1+1=3

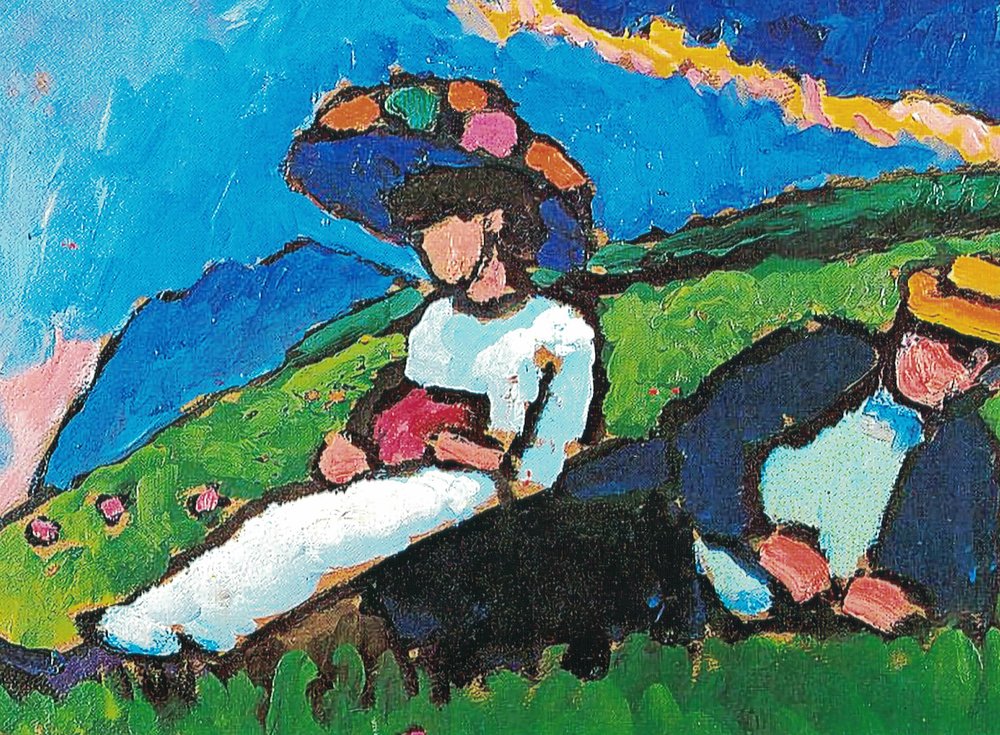

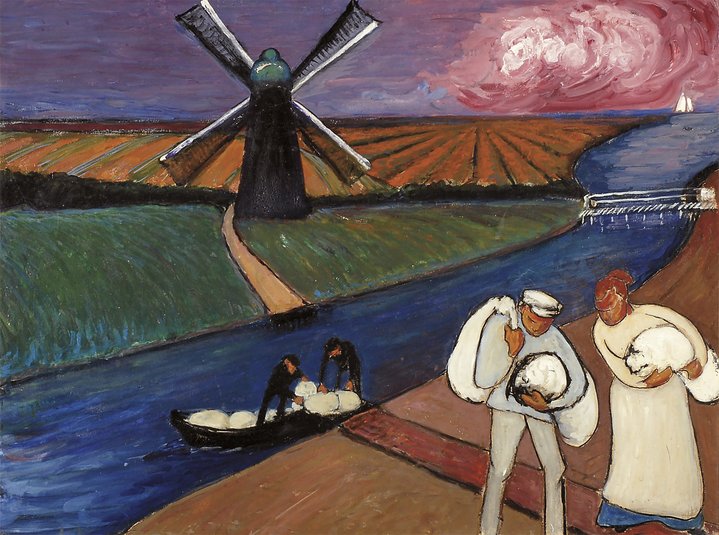

Gabriele Münter. The artists Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, 1909 (Fragment). Städtische galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich ©

Post-war Russian art is overshadowed not by an artist, but by a power-couple, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. With their extraordinary cultural legacy, are they really the nation’s greatest partners in life and art?

Like an art collection, a power couple is greater than the sum of its parts – or partners in this case. Although the term itself dates from the mid 1980s, over the past decade, with the public’s growing interest in female artists, the identity of artistic genius, once limited to a white male, has come also to embrace not just one solitary figure, male or female, but two creative soulmates. Artists for whom life and art are joined. Their relationship creates sparks and, in some cases, builds the foundation of whole art movements. The creative electricity between Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) sparked off rayonism, possibly the only 20th century ‘ism’ to be created entirely by a cohabiting couple.

Although the term ‘power couple’ is more a product of our time of influencers, brands, and labels and the Kabakovs are its posterchildren, it was modernism and the Russian avant-garde, which saw a striking and unprecedented number of artistic couples, where both artists created their own legacy, distinguished from their significant other and yet inextricably entwined.

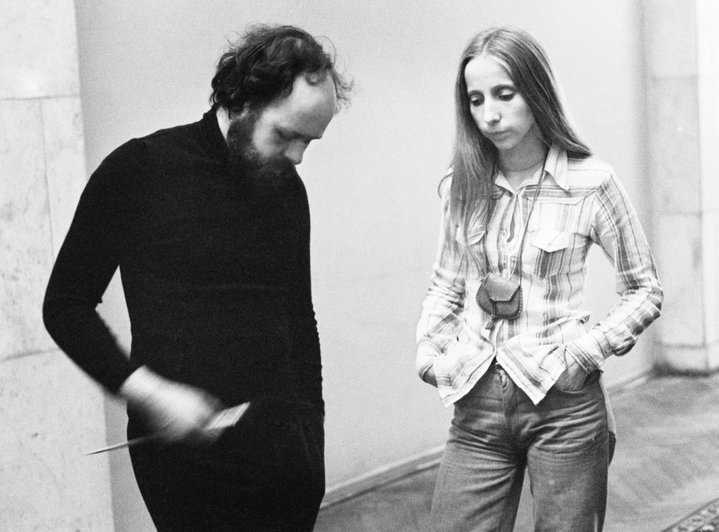

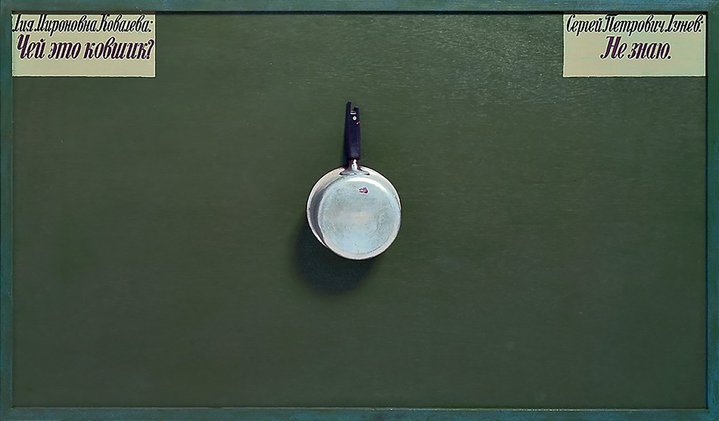

Among their contemporaries, there were many other artist duos who are life-long companions working together, such as Makarevich (b.1943) and Elagina (b.1949), the Gerlovins (b.1951) and the Cherkashins (b.1948 & 1958), whose names are more often pronounced together than apart. Igor (b. 1954) and Svetlana (b. 1950) Kopystiansky, whose later work is more collaborative, created conceptual paintings during the Soviet times, her text paintings proving more popular with collectors than the destroyed paintings of her other half. All of these artists are conceptualists for whom their market value hardly registers on international market reports, their legacies are more cultural, so they are hard to assess in economic terms. Andrey Monastyrski (b.1949) and Irina Nakhova (b.1955) are perhaps among the most original and fascinating artists of the Moscow conceptual group, both have been courted by museums around the world and have represented Russia at the Venice Biennale in the past decade, Nakhova left home to live with Monastirsky when she was just sixteen, sparking off a period of intense creativity which led to her genre defining ‘Rooms’ total installations (1983–87).

Financial results are one criteria, but there are questions also of balance and equality both cornerstones of authentic power coupledom. Where one artist has a stellar market presence and the other little to none, or no accountable market prices, it gives us pause for thought. We also ought not to forget here the hinterland in which women existed. During the late Soviet era, there seem to have been a considerable number of women selflessly dedicating themselves to their husband’s life’s work, many of whom have become beloved subjects of these works, such as Oleg Vassiliev’s (1931-2013) wife Natasha, whose work we cannot imagine without her haunting image. It is as if the brakes were put on the fast pace of the Russian Avant-Garde’s positioning of women at the forefront of new developments in art and, after the war, things settled back into what might have been the status quo in the previous century. It casts something of a shadow over the late Soviet period.

Under that shadow and far below the Kabakovs’ record six figure prices are nevertheless two distinctive contemporary artist couples - Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016) and Lydia Masterkova (1927-2008); and Oscar Rabin (1928-2018) and Valentina Kropivnitskaya (1924-2008). All four were members of the Lianozovo group, Soviet Russia’s first underground artist community, based in a barrack outside Moscow. Nemukhin and Masterkova never married and did not last the course as a couple, but the other pair did and the 2015 film ‘In Search of a Lost Paradise’ chronicles their life together described in the film by writer Liudmila Ulitskaya as crammed: “It was very hard for two such different artists to live in such a small place and not to get in each other’s way.”

To define what a power couple is in the most liberal sense of the word can include same or opposite sex partnerships, in marriage or outside and they do not need to last a lifetime. According to pricing on the international market, one of the greatest artist power couples of all time was Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) and Jasper Johns (b. 1930), who were together for only six years, a period during which they produced their best work in which their relationship was a crucible to their artistic development. This is key to being a power couple: interdependence where both individuals support each other as equals, account for their differences in personality, complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses. As artist Sonya Stereostyrski, one half of the PPSS duo who are partners in both art and life, says of their independent work, “we do not influence, rather inspire and support one another.”

Artist hierarchies based on market value are commonplace in discussions around which artists may be the greatest, even if we know market value and art historical value are not one and the same. We love to know that Mark Rothko is currently the most expensive Russian contemporary artist (Rothko was born in Latvia when it was part of the Russian Empire). Can we ask this about artistic couples?

Here, at the outset, there is a problem. Where Ilya Kabakov’s market value brings him to the top of the leader board as Russia’s most expensive contemporary and living artist, Emilia Kabakova does not have an independent body of work with which to judge her own legacy. Further, many of the preoccupations in Ilya’s early work also continue to thread throughout the work they have been producing together since the late 1990s, when they became a couple. Yet, surely, there is no question that Emilia’s legendary strength of will and personality, her iron clad determination to break down any barriers, her dedication and passion is something which has undeniably resulted in a body of work that otherwise would simply not have existed. The world would be less bright and missing a cultural link without these now famous collaborators.

Marianne von Werefkin. Styx, 1910–1911. Oil on thin card laid down on cardboard. Courtesy Christie's

Among their contemporaries, there were many other artist duos who are life-long companions working together, such as Makarevich (b.1943) and Elagina (b.1949), the Gerlovins (b.1951) and the Cherkashins (b.1948 & 1958), whose names are more often pronounced together than apart. Igor (b. 1954) and Svetlana (b. 1950) Kopystiansky, whose later work is more collaborative, created conceptual paintings during the Soviet times, her text paintings proving more popular with collectors than the destroyed paintings of her other half. All of these artists are conceptualists for whom their market value hardly registers on international market reports, their legacies are more cultural, so they are hard to assess in economic terms. Andrey Monastyrski (b.1949) and Irina Nakhova (b.1955) are perhaps among the most original and fascinating artists of the Moscow conceptual group, both have been courted by museums around the world and have represented Russia at the Venice Biennale in the past decade, Nakhova left home to live with Monastirsky when she was just sixteen, sparking off a period of intense creativity which led to her genre defining ‘Rooms’ total installations (1983–87).

Financial results are one criteria, but there are questions also of balance and equality both cornerstones of authentic power coupledom. Where one artist has a stellar market presence and the other little to none, or no accountable market prices, it gives us pause for thought. We also ought not to forget here the hinterland in which women existed. During the late Soviet era, there seem to have been a considerable number of women selflessly dedicating themselves to their husband’s life’s work, many of whom have become beloved subjects of these works, such as Oleg Vassiliev’s (1931-2013) wife Natasha, whose work we cannot imagine without her haunting image. It is as if the brakes were put on the fast pace of the Russian Avant-Garde’s positioning of women at the forefront of new developments in art and, after the war, things settled back into what might have been the status quo in the previous century. It casts something of a shadow over the late Soviet period.

Under that shadow and far below the Kabakovs’ record six figure prices are nevertheless two distinctive contemporary artist couples - Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016) and Lydia Masterkova (1927-2008); and Oscar Rabin (1928-2018) and Valentina Kropivnitskaya (1924-2008). All four were members of the Lianozovo group, Soviet Russia’s first underground artist community, based in a barrack outside Moscow. Nemukhin and Masterkova never married and did not last the course as a couple, but the other pair did and the 2015 film ‘In Search of a Lost Paradise’ chronicles their life together described in the film by writer Liudmila Ulitskaya as crammed: “It was very hard for two such different artists to live in such a small place and not to get in each other’s way.”

Nemukhin and Masterkova’s combined individual record prices of over $300,000 and the large quantity of works offered on the international auction market exceed those of Rabin and Kropivnitskaya. Although Nemukhin’s record for the sale of a painting outstrips that of his wife by nearly double, for graphic works her record is the greater for ‘Composition Pryluky’ (1960-61), sold at Vladey in 2019 for $67,224. During the brief years they were living together throughout the 1960s, their work was quite similar, they were both abstract painters, they applied objects and material to their canvasses; they were consciously self-styling themselves as heirs to the avant-garde; they had interest in formalism and their palette became more monochrome over time. However, this common ground brought different solutions and, apart from a brief period in the 1960s, their art is distinguishable.

Of their Lianozovo double daters, most people would recognise Oscar Rabin as the far greater of the pair. Certainly, his market results justifiably exceed those of his wife Kropivnitskaya (there are two paintings that share the top price for Rabin: ‘Baths’ and ‘City with Moon, Socialist City’). However, when it comes to graphics, they are closer together: only three results for works on paper by Rabin beat her auction record of $15,606 for a work sold at Sotheby’s in 2006. Their art, despite being figurative, is completely different, suggesting that as a creative couple Rabin and Kropivnitskaya each had a level of independence and authenticity, which sets them aside from those couples whose work is far closer in style. Their total combined top results fall below $300,000, but not by far.

History shows us that power couples do not have to be together forever, like Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and Gabriele Munter (1877–1962), who were partners for around a decade. With hindsight, it looks like their relationship was a crucible in part for the art Kandinsky produced around 1911. It came after several years of travelling around Europe a deux, where they both painted together, producing landscape sketches many of which are remarkably similar. Once they had settled in a small rural village in Bavaria in a house she bought, it produced an environment conducive to Kandinsky’s breakthrough into abstraction. Munter was under no illusion: she was Kandinsky’s “side-plate”, Franz Marc believed she was even a distraction. Yet, they had complementary personalities; she painted in a rather spontaneous, fast manner; Kandinsky was a cerebral ex-lawyer, a teacher eleven years her senior.

You might disqualify them for being an intercultural couple: he was Russian, she German, they never married and were not partners for life and, again, there was a lack of balance; she did not change the path of art history and pave the way for contemporary art as he did. Artists Alexey von Jawlensky (1864–1941) and the aristocratic Marianne von Werefkin (1860–1938) were both Russian, becoming a couple after having met in Repin’s studio in 1891. It’s hard to claim equality here either: she gave up painting for nearly a decade to support him and his record on the market at $16.6 million for his portrait of Schokko shouts in the face of her $550,000 achieved for ‘Styx’ sold at Christie’s in 2008. However, later, Werefkin did return to painting and a book recently published referring to them as “soulmates”, explores their relationship and how they contributed to modernism both as individuals and as a couple.

If you are looking for both the perfectly balanced power couple and electrifying auction results it would be the modernist Russian painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov. They tick just about every box you can throw at them. First off, despite the drag on prices for female artists historically, her prices are higher on the market today than his. She was earth to his air; she came from sculpture (God formed humans from clay) and he came from impressionism (all about light). She was from a noble background and Larionov socially her inferior, her parents considered them a bad match. During their most important years before the Revolution in Russia, their work is often so close that it is impossible for experts to distinguish them apart, as many paintings are unsigned. I know collectors who bought a painting by Larionov thinking, “well, ok, if it is his work, but even better if someone comes along later to tell me I have a Goncharova!” Socially, they were both influential and were at the centre of many of the developments of the avant-garde, at the cross-roads of Italian Futurism and French Fauvism, a hatching of Russian Cubo-Futurism. So who was the better artist?

Although Larionov and Goncharova’s top auction records combined surpass those of two other august power couples of the Russian avant-garde, Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) and Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958); and Robert and Sonya Delaunay, the latter’s market results are the most balanced I can find in terms of public sale records. Robert Delaunay’s top price at auction achieved in 2012 for his 1926 ‘Tour Eiffel’ was $5.2M, his wife Sonya Delaunay’s record price, made ten years earlier, was $3.9M. And even then, her presence on the art market is far more established, thanks to her work as a print maker, literally thousands of fine art prints have been sold on the international auction market over the past 30 years. Perhaps this also shows the importance of yet another measure for assessing power: quantity. There is nothing quite like bringing thousands of your own works into as many sitting rooms as you can, all around the world.