Shades of grey: the rise in contemporary Russian art forgery

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

Discover three Russian contemporary artists whose works are frequently faked – and the ways to check their authenticity. Art market expert Jo Vickery throws much-needed light on the shadiest corners of the Russian art scene.

The Russian Avant-Garde is famous for forgeries which have long undermined the legacies of the country’s greatest artists. But what about contemporary Russian art?

For obvious reasons, it is usually after an artist’s death that the fake industry starts re-inventing his or her output on a major scale. As the first generations of Soviet unofficial artists grows older, forgeries are increasingly becoming a problem for collectors. However, even living artists are not immune from that plague.

Unlike the Russian art of the early 20th century, the problem is not widespread, but it is nevertheless becoming a growing concern. The contemporary Russian art market has grown up and there is a new battery of star artists fetching six figure sums. However, the increase in values is raising the stakes. How to deal with this?

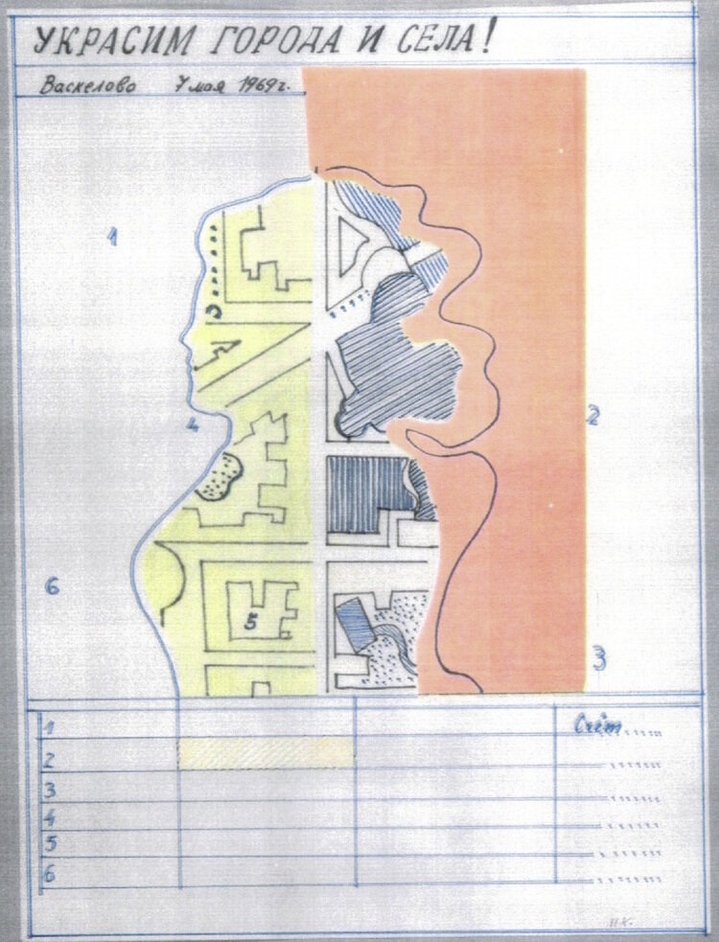

The process of determining authenticity is often one which involves many shades of grey. Catalogues raisonnés are the best way for an artist to protect his or her legacy. However, art produced underground during the Soviet era, much of which was discretely sold for cash or even exchanged for prized objects from the capitalist West, went unrecorded. If the artist is no longer alive, this makes it difficult for art experts today to trace and authenticate. Exhibitions held during the lifetime of an artist are one of the ways one can authenticate works. However, many shows during the 1970s–1990s took place in private apartments and left no paper trace.

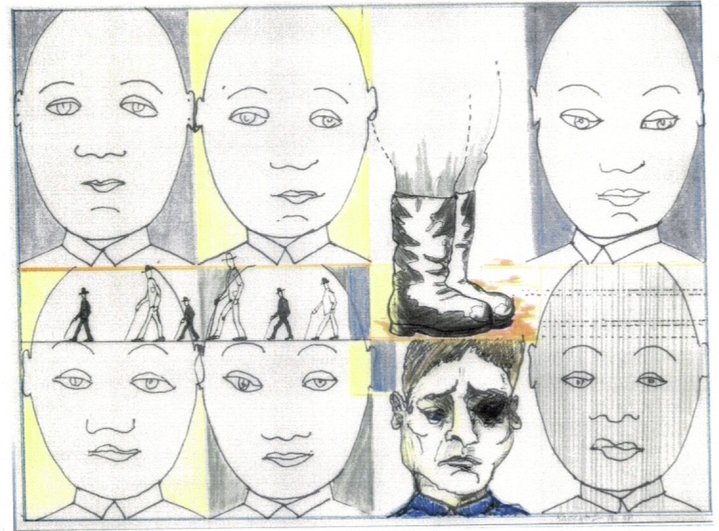

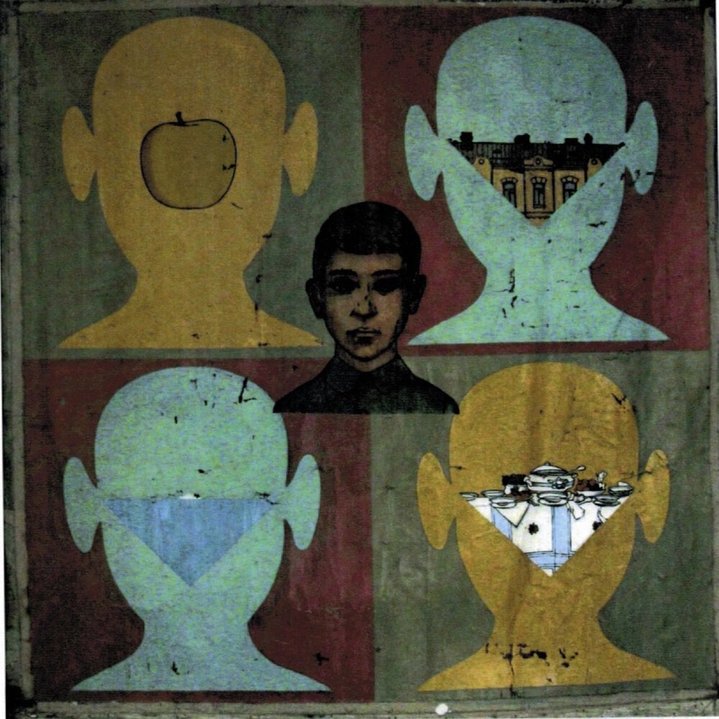

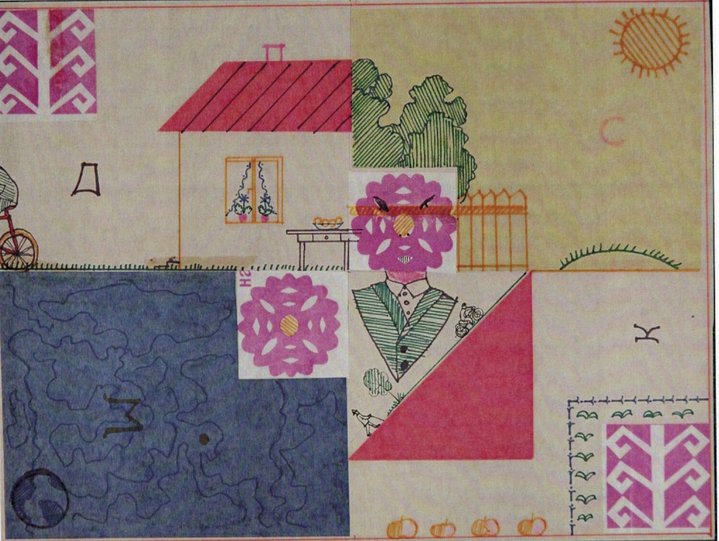

The Russian-American artist duo Ilya (b. 1933) and Emilia Kabakov (b. 1945) have long grappled with such issues. Alongside Ilya’s studio is a space like a laboratory, piled high with files of documents well organised and ordered. The Kabakovs have already produced catalogue raisonnés for his paintings and their installations. However, Emilia admits the plan to publish a catalogue of his drawings is still a work in progress and that their own photographic archive of drawings before 1996 is not fully complete. Predictably, it is precisely early fake ‘Kabakov’ works on paper that are circulating the most on the market.

Works on paper are notoriously hard to authenticate. They are also normally far more numerous and more difficult to trace. With Kabakov’s drawings selling in excess of 10,000 USD, there is good incentive for fakers.

The nature of conceptual art itself can lead to another type of fraud, a kind of art vandalism. Emilia Kabakova explains how she often comes across drawings, once authentic works by Ilya, which have been embellished with new pictorial details, texts and perhaps even a fake signature to create a new, but sadly no longer original composition.

Anyone wanting to authenticate a drawing by Ilya Kabakov should go to the family. Ilya is, for instance, training Emilia's granddaughter Orliana Morag to identify key markers and characteristics of such works so that she can play a role in supporting his legacy.

If there is no reputable catalogue raisonné, experts play the main role by default and this is where expertise most often falls into shades of grey.

This is especially the case if provenance is missing, vague or impossible to corroborate. Unless an expert has produced extensive peer-reviewed material on one specific artist, relying on a single ‘guru’ to authenticate a work of art can be inviting risk.

It’s wiser for collectors to consult all those with legitimate claims to know the artist’s work well. These can be family members, gallerists, art historians or curators and all of them ideally need to come to the same conclusion on authenticity independently. Disagreements happen frequently and, unless a consensus is reached, it can negatively affect the value of a work and lead to a buyer refusing to recognise it as genuine, even if it really is.

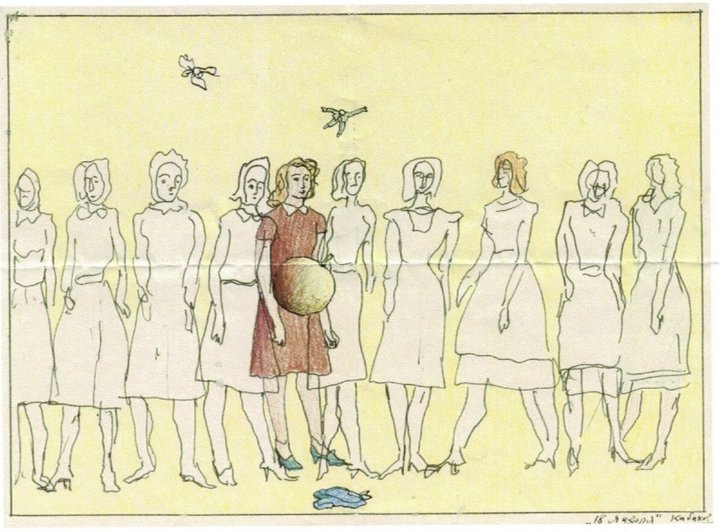

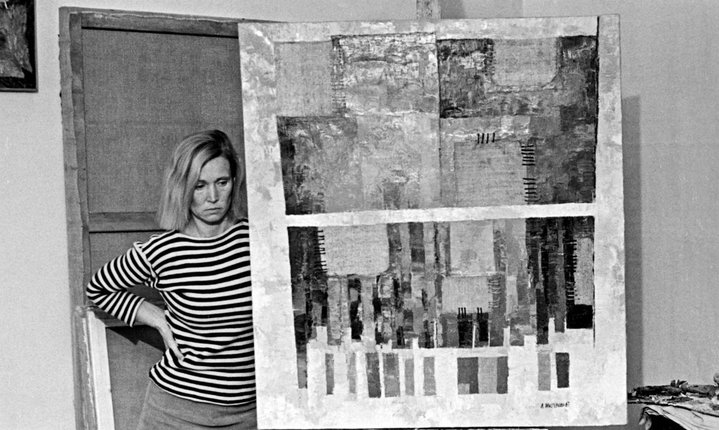

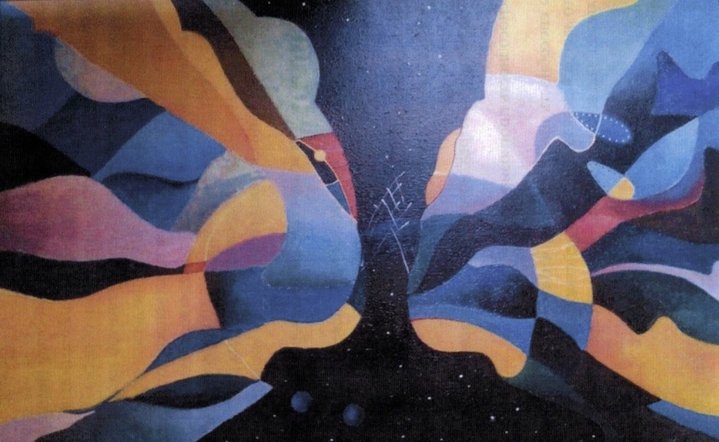

Two artists whose paintings have become more popular and more valuable are Lydia Masterkova (1927-2008) and Georgy Gurianov (1961-2013). Their oeuvre is not yet fully documented, which makes them particularly attractive to forgers.

Predictably, fakes are appearing on the market. Masterkova died in 2008 when her art was only beginning to attract wider attention. Documented works painted before she emigrated to France in the mid-1970s are scant, and yet tragically, this is her most important period as an artist. Masterkova’s niece, writer and curator Margarita Tupitsyn, is well placed to give an informal view on the artist’s work. Respected art historian Valery Silaev, who specialises broadly on the art of the 1960s, is also intimately acquainted with her work.

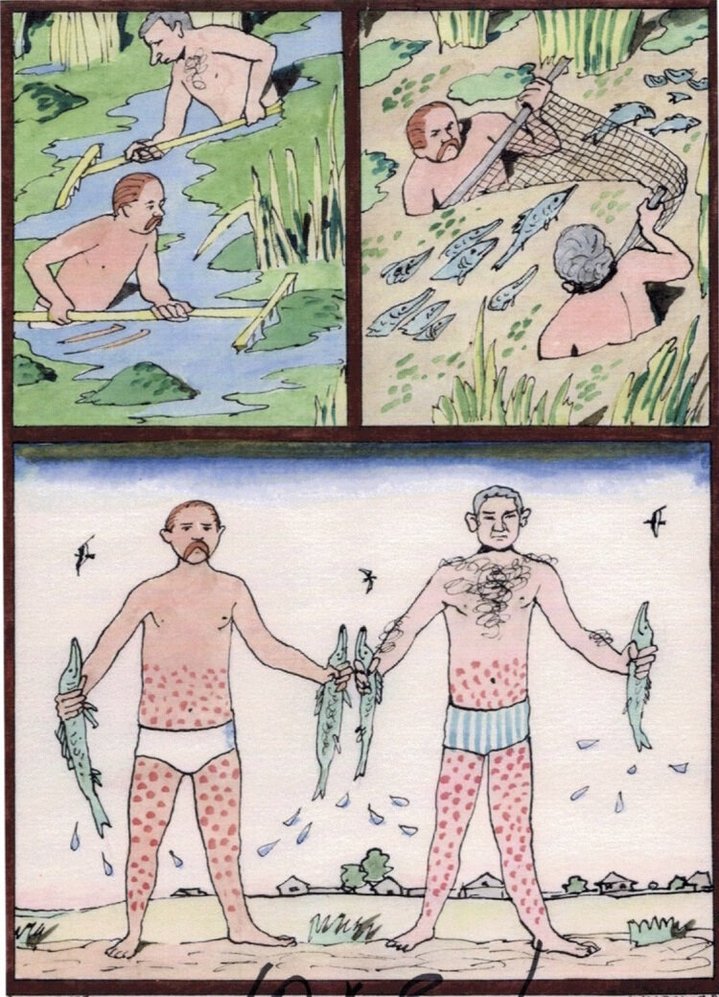

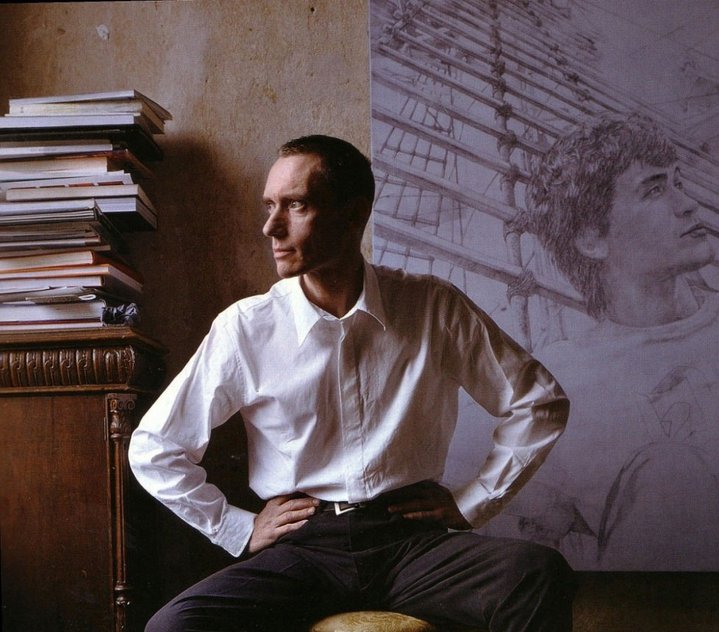

The Leningrad-based painter Georgy Gurianov (1961-2013) was planning to produce a catalogue raisonné and create a foundation, but he died after a long illness without being able to achieve either of those goals. His legacy had not been subjected to forgery during his lifetime. However, the first fakes surfaced soon after his death.

For collectors wishing to check the authenticity of paintings and drawings by Gurianov, there are several people who worked closely with the him and whose opinion is worth seeking. They include art historian Arkady Ippolitov, and artists Olga Tobreluts (b. 1970) and Andrey Khlobystin (b. 1961). Gallery owner Olga Osterberg collaborated closely with Gurianov from the year 2000 and knows the last decade of his work.

Paintings and drawings without clear provenance sometimes lead to long, heated debates before a final view is reached. Even then, scholars’ views can change over time. Prices for such works are undoubtedly lower than those whose provenance is clear.

The embryonic problem of fakes in the Russian contemporary art field is likely to grow in future and demands ever higher levels of expertise and professionalism. Forgers are increasingly sophisticated, although there are exceptions.

In the murky world of fake art, truth can sometimes be stranger than fiction. Emilia Kabakov told me how a gallery owner asked her to check a drawing. It was an open and shut case, an obvious fake. The gallerist agreed that she should write “fake” across it. However, he asked to wait until he had discussed it with his clients. It turned out they were connected with the Russian Mafia and they told him not to worry: “It’s ok, she can destroy it. We’ll make another one."