Safety in numbers

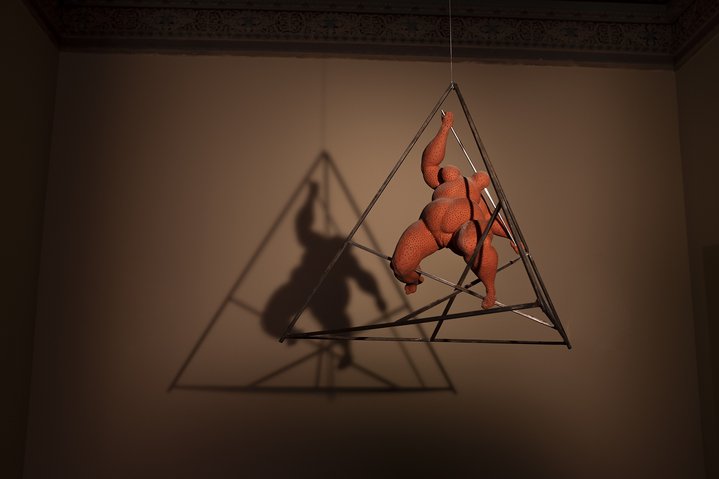

CUBE Moscow. Artwork by Irina Korina at the inaugural exhibition "Sans (t)rêve et sans merci." 2019

Moscow’s galleries seek new forms of collaboration and invent unusual business models in order to increase reduce costs and expand their customer base. Good luck to them.

Theories as to why the Russian domestic art market remains depressed are numerous, but they can all be summarized with Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s famous quote: “There’s no money, but just hang in there!” In a city of Moscow’s scale, with its enormous population and well-established museum scene, one could be forgiven for thinking that no stone remains unturned; on the other hand, as Simon Hewitt noted in issue 3 of Russian Art Focus, the prices that Russian contemporary art fetches on the international market remain disappointing. Ordinary Russians certainly don’t have the disposable income to spend on art, as the country continues to reel from the 2014 crisis, while “extraordinary” Russians (read: oligarchs) prefer more durable investments. However, the latest wave of new galleries and art spaces are not as concerned with building collections for their buyers. They are setting their sights on becoming gathering spaces for the art community, popping up in the most unexpected places, from abandoned mansions and basement cafes to a disused space beneath a five-star hotel. However, each space mentioned here takes a non-traditional approach and the results are wildly popular.

CUBE Moscow is located underneath the Ritz-Carlton on Tverskaya, the main street leading to the Kremlin. Visitors step past the line of waiting limousines into a back alley where a service elevator lowers them into the hotel’s bowels and a sprawling underground space divided into stalls and a communal exhibition hall, which the galleries occupy in turns. Two of Moscow’s existing galleries have set up shop there, Kultproekt and Rublyovka’s Gridchinhall, and it has become the only location for others such as Fragment Gallery and several newcomers. Its opening on 14 February was attended by thousands, and the most recent Art Weekend on 22 March showed no sign of letting up. The space operates on the principle of “cost sharing.” Each gallery pays a fee that partially covers the rent and operating expenses of the space. Although it resembles an art market, it seems explicitly designed to become a gathering space, with a coffee bar operating during the week and a wine bar that works on opening days. CUBE’s future plans are no less ambitious: on 23 April, it will host an international Collectors’ Summit, gathering experts and prospective buyers (along with a staggering 25,000 ruble entrance fee — nearly $400). Rumour has it that CUBE Moscow is only the first in a series and that its chairman, the Swiss businessman, diplomat and art collector Uli Sigg, has plans to open similar locations abroad.

This is not the first hotel gallery in Moscow. Richter, a boutique hotel and art space, opened last September and quickly became a centre of attraction for Moscow's legendary “tusovshchiki” (Russian for “party people”). The party is, however, secondary: sharing space inside Richter with a “vermoutheria” and a pirate radio station is Szena ("Stage" in Russian), an art gallery helmed by Anastasia Shavlokhova. Previously known for running the philosophy club in the Winzavod art cluster, she has gathered artists ranging from contemporary classics like Oleg Kulik to an immersive theatre performance by CO-TOUCH, called the Museum of Sensing Practices. This describes itself as “a new museum format that needs no space, no material objects, and no works of art.” A second, smaller gallery, The Ugly Swans, opened later, led by the artists Dmitry Vrubel and Arseny Zhilyaev. Often referred to as the “hidden room,” they position themselves between major museums and underground art spaces as an alternative to major commercial galleries. They associate themselves instead with the Sreda Obucheniya (Educational Environment) network of higher educational institutions. The team of 12 curators includes such stars as theatre director Maxim Didenko and Moscow International Experimental Film Festival founder Vladimir Nadein. Here, the concept of shared space proposed by founder Anastasia Efimova is taken to extremes: during the day, it is not unusual to see young creatives on their laptops, while black-clad revellers move in on evenings and weekends. Nevertheless, the art on display never becomes a mere background, whether inspiring daytime productivity or a neon-tinged Instagram photos.

Another format, the cafe gallery, is alive and well. It is, of course, not unusual to see a cafe or restaurant decorate its walls with works by local artists. It is less usual to see the gallery become the main event. The most famous such location, Perelyotny Kabak (“The Flying Inn”), looks like a run-of-the-mill basement wine bar from the outside, but turn the corner by the kitchen and you find yourself inside Maxim Bokser’s intimate gallery stretching across several rooms in the same basement. Each month, the main space hosts a new contemporary art exhibit curated by Bokser and Vladislav Efimov, while the “second gallery” hosts guest projects from young artists and curators. Fixtures of the Moscow art scene like Irina Korina and David Ter-Oganyan share space with rising stars like Igor Samolyot (famous for his inflatable social media statues). In daytime, one can even visit a yoga lesson. Another space, Art Bar Palikha, puts a more traditional emphasis on food and drink, but its programming is original. Mixed in among the concerts and poetry readings are one-day art sales, where an invited artist brings in their works and, betting on the pressures of time and scarcity, only puts them on display for a single evening.

The senior gallery among this group, Kovcheg (“Ark” in Russian), has a pedigree stretching back to the perestroika years. As a creative collective, it first appeared in 1988 and has collaborated in various forms with organizations as important as the State Pushkin Museum and the State Tretyakov Gallery. The gallery has a long experience of space-sharing but now occupies a basement space off Moscow’s New Arbat Street. Curators Sergey Safonov and Igor Chuvilin frequently work with other museums and international art markets bring Russian artists of the 20th and 21st centuries to the world’s attention. Although Kovcheg is the most traditional of these galleries, its history of collaboration and space-sharing earns it a place on this list.

It is hard to judge any of these spaces purely on the merits of the projects they have presented thus far. Some are only gathering momentum; others claim to break with traditional museum and gallery conventions, prioritising a whole new paradigm of space use. One thing is for certain: they are bringing exciting changes to today’s Moscow art scene, and promise to challenge both established commercial galleries and state museums in terms of both attendance and attention in the coming months — and, hopefully, years.