Rustam Suleymanov: the Moscow patron of Muslim art

The businessman, collector and founder of the Mardjani Foundation supports art from Islamic regions both in and outside Russia.

Rustam Suleymanov has been called the “Islamic Tretyakov” for putting Muslim art and artists on the map in Russia, just as the collector Pavel Tretyakov (1832–1898) enshrined Russian art.

His Mardjani Foundation, launched in 2006 and named after a progressive 19th century Tatar theologian and historian, is headquartered in a nondescript Soviet-era building and his office is filled with contemporary paintings wrapped for transport.

Although his collecting started with a work by the renowned Russian portrait painter Valentin Serov (1865–1911), a classic artist much admired by Pavel Tretyakov and today’s wealthy Russian art lovers, it soon turned towards uncharted but deeply personal waters.

“If Russian art of the early 20th century was initially interesting for me, the next stage was understanding my identity,” said the wiry and pensive Suleymanov.

“It’s one thing to simply have some paintings to decorate your home or office and quite another when a collection outgrows this decorative dimension… I started contemplating what I wanted to say, what contribution I wanted to make.”

His search for an overarching theme led him to his own heritage and grew into a collection that now numbers around 10,000 works.

“I gradually reoriented to Islamic art – Islamic in a rather broad sense, from medieval classics to the contemporary,” he said. “I was surprised to find that Russia, which has such a rich Islamic history does not have a specialized museum of Islamic art.

Suleymanov, who is Tatar, was born in Uzbekistan. Educated as a physicist, he made his fortune in businesses such as packaging, and is now known for a chocolate brand.

He hopes to open Russia’s first Islamic art center in partnership with a major state institution. His foundation also sponsors scholarly research. Anton Pritula, an Islamic art expert at the Hermitage Museum, told The Art Newspaper in 2013 that the Mardjani collection is second only to the Hermitage’s in Russia, and is approaching the Aga Khan’s in breadth.

Suleymanov’s interest in Muslim contemporary art has opened a window to large parts of Russia and the former Soviet Union which have been under-represented elsewhere.

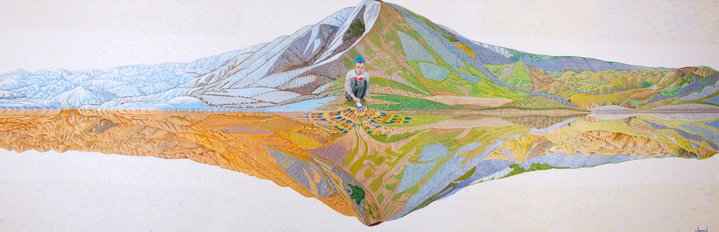

This year, his foundation has staged several shows in Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan: most recently, “The Golden Horde and the Black Sea Region,” in partnership with the Hermitage’s Kazan outlet, as well as an exhibit of contemporary artist Alexander Akilov (b. 1951), a native of Tajikistan who works in Moscow and Germany.

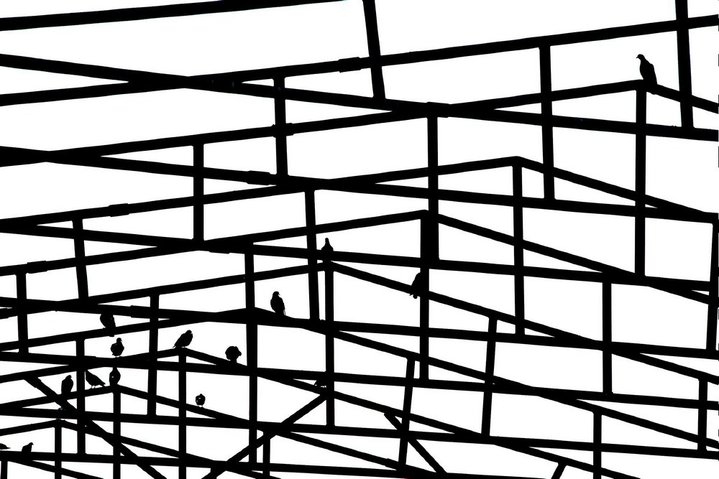

“Transformatio” was a group show at St. Petersburg’s Erarta Museum featuring contemporary artists from Dagestan in the Northern Caucasus, ranging from Magomed Kazhlayev (b. 1946), a painter associated with the Soviet Non-Conformists, to Taus Makhacheva, who studied in London and is known for her performance and video art.

Suleymanov would like to work with the Nukus Museum, home to a treasure trove of Russian avant-garde art in the remote Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan, which is beginning to open up after years of dictatorship, according to the collector, but still has a complex cultural bureaucracy.

Azerbaijani artists are prominent in Suleymanov’s collection, especially Gayyur Yunus (b. 1948), whose work “interweaves elements of Iranian Qajar art of the late 19th century with the influence of Niko Pirosmani” (1832–1898), the Georgian naive painter.

When buying, Suleymanov tends choose up to five paintings from an artist over time. Works can be difficult to price in that context, but he said that such acquisitions typically ranged from $5,000 USD to $50,000 USD.

Regarding Russia, Suleymanov says, “We are all very closely connected with each other. We are all in one big ark, but this connection and interdependence is most vividly manifest in the most diverse regions that have deep traditions of peaceful coexistence.”

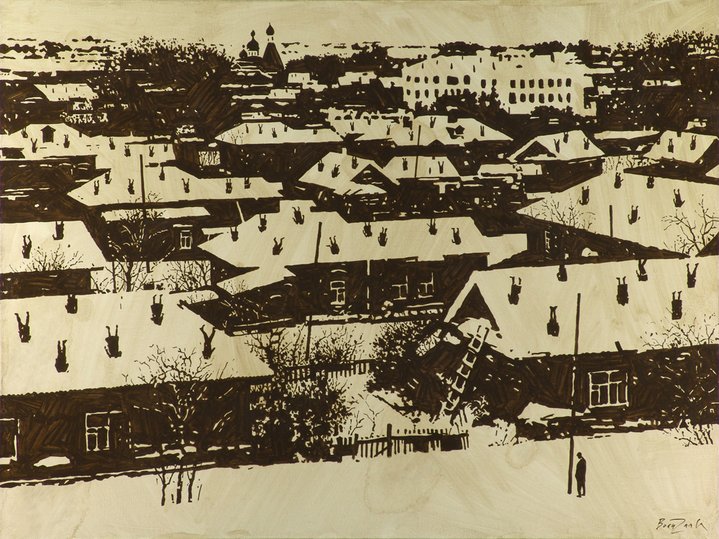

A common Soviet heritage is apparent in the work of Rinat Voligamsi (b. 1968), who flipped the spelling of his last name, Ismagilov, to distinguish himself from other artists. The Foundation sponsored “Dvoegorsk,” a solo show of Voligamsi’s works organised by Moscow’s 11.12 Gallery at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA) in 2018, in which paintings and installations were used to create an eerie Soviet utopia in a fictitious military town.

Suleymanov describes these as works that depict a Soviet past “that we are barely pulling out of ourselves,” and adds that it is “impossible to say that it is easier for artists or people who live in the Northern Caucasus or Tatarstan or Bashkortostan or even Uzbekistan to reject Soviet identity than for a Russian living in the provinces. [...] Each person has the voice of the earth and the voice of blood, but the voice of the times also speaks.”

Voligamsi, he said, offers a “penetrating and ironic view on identity, a conversation about ourselves,” that can be humorous and biting without being painful or degrading.

Russia has tough laws both on religious extremism and artworks that “offend religious feelings.” Suleymanov said he doubts that “art is capable of offending” true believers, even if in the Middle East it has led to riots over offensive depictions of Islam. “I think it is even strange that there are laws or court rulings” about this, he said.

However, he will not buy works for his collection that are “too radical,” and questions their aesthetic value. “Can something that aims to offend be regarded as a work of art?” he asks. “If before art was defined by ethical and aesthetic principles, now many things are trivialized and coarsened."

Artists such as Taus Makhacheva (b. 1983) show that it is possible to address local issues, life and traditions in Muslim regions like Dagestan while speaking to an international audience.

“In spite of the fact that she is a contemporary artist in form and in technique, her Dagestani roots are nevertheless apparent in her work,” Suleymanov said. “We see above all that she is keenly interested in this land. She has her own point of view, but it is not that of someone on the sidelines. It is the viewpoint of a person who is acutely concerned about her native land, about the changes taking place there.”

Marjani Foundation