Marat Guelman: time to give

An unexpectedly generous gift to the State Tretyakov Gallery from the "Enfant Terrible" of the Moscow art world.

Marat Guelman (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities), a Russian contemporary art pioneer and one-time political guru, distanced himself from Putin’s Russia in 2014 after it annexed Crimea and became embroiled in military conflict in eastern Ukraine. Guelman has settled in a luxury housing complex in Budva, a Montenegrin resort overlooking the Adriatic Sea. Even though he remains based there, he made a creative return to Moscow last October, staging an exhibition about the political protest artists. His latest plan is to make a major donation of works from his personal collection to the State Tretyakov Gallery. An exhibition of these artworks opens for the public on 15 February.

“I’m giving Kabakovs’ big installation ‘The Tennis Game’; two big installations, one by the Blue Noses, another by [Gosha] Ostretsov; works by [Vladimir] Dubossarsky; old works of [Dmitry] Gutov,” he said, rattling off the names of artists he knows well and whose works were primarily given to him by them.

“It is very important to understand I’m not an oligarch,” he said in a Skype interview in January. “I am 60 years old, but I continue to work, to earn some kind of money… All that I have is thanks to artists, so I always do everything in their interest.” He sees the collectors’ priority as being “getting their works into museums, in good collections, and that, from these museum collections, they (the art works) start circulating all over the world.”

Guelman donated 50 artworks to the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in 2000 and later gave six works to the Centre Pompidou as one of the contributors to a mass donation of Russian contemporary art organised by billionaire philanthropist Vladimir Potanin in 2016. Despite Russia’s political clampdown, Guelman says he feels confident donating to the Tretyakov, since contemporary art has become a priority under its director, Zelfira Tregulova, and her advisor, Faina Balakhovskaya. “Their ideas about contemporary art coincide with mine.”

He has also been influenced by seeing wealthy friends waver, sometimes tragically, over donations. It has taught him the importance of giving at the right time. “I understood it’s necessary to think far in advance about finding a good place for art works since the circumstances might change and it won’t always be that you are sitting like a king and museums are circling around you and begging you,” he said.

He also wants to set an example.

“I regard myself as a kind of mentor to collectors and artists,” he said. “At the same time, when I meet collectors, I always tell them it’s necessary to think in advance about the fate of their collection.”

Guelman was born in 1960 in Kishinev, the capital of Moldova, in the southern reaches of the USSR, the son of Alexander Guelman, a prominent screenwriter and playwright. Marat, however, made his rise to the top of the fledgling gallery scene via Ukrainian art.

“My career as a gallerist began with an exhibition called ‘The Southern Russian Wave’,” he said, which featured artists such as Arsen Savadov, Oleksandr Roytburd and Sergey Anufriev. “In 1988, after Sotheby’s [highly successful Moscow contemporary art auction], artists’ heads were spinning in the capital. Prices spiralled. I didn’t have the financial means to buy what I liked, so I went south to collect and found a very interesting group of artists. Now they call themselves the Ukrainian transavantgarde. There was a sense that there was so-called ‘Moscow Romantic Conceptualism’ and nothing else in Russia in terms of contemporary art. Then two alternatives appeared. One was small and calm, Timur Novikov with his Petersburg Academy [New Academy of Fine Arts in Leningrad]. The second was this powerful Kiev wave.”

“For the first four years my gallery was jokingly referred to in Moscow as the Ukrainian Mafia,” said Guelman. “These are very important artists, and they continue to be important”.

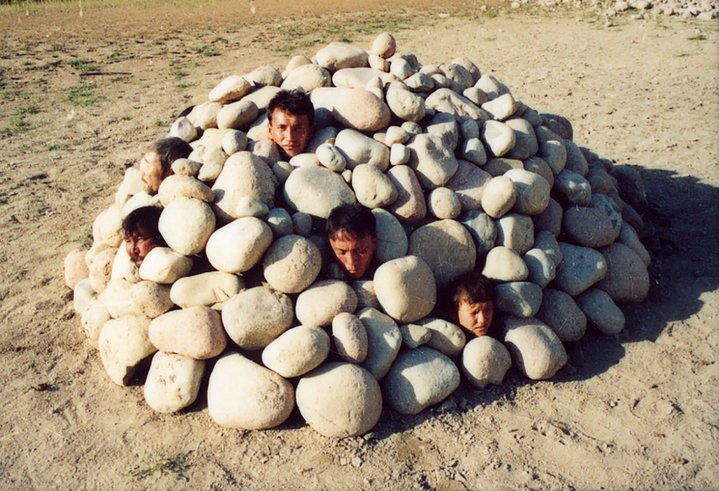

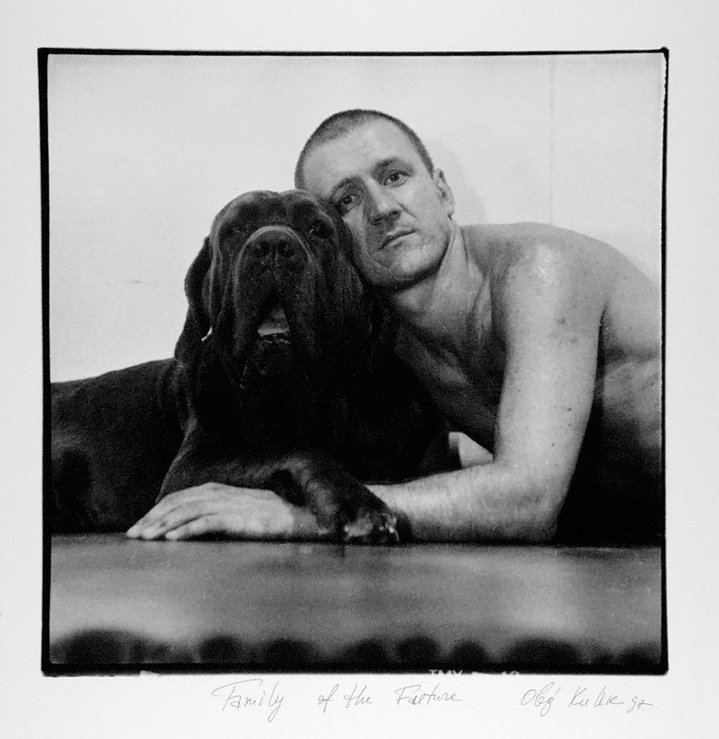

He also drew media coverage thanks to another Ukrainian-born artist, Oleg Kulik, whose first legendary ‘Mad Dog’ performance took place outside Guelman’s original gallery space in 1994. Guelman positioned his gallery as a space for alternative art, also showcasing other actionists such as Anatoly Osmolovsky (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities), Alexander Brener and Alena Martynova, but also worked with titans such as Ilya and Emilia Kabakov and the Sots-Art duo Komar & Melamid.

Oddly, Guelman then also became a political gun for hire, working on various Russian and Ukranian election campaigns. However, he grew increasingly at odds with the Kremlin and eventually decamped to India after being condemned by the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2008, he made a comeback as curator of Russian Povera, a seminal exhibition of Russian contemporary art in the economically depressed industrial city of Perm. He was appointed director of PERMM, a contemporary art museum and he became the producer of a cultural revival supported by Oleg Chirkunov, a forward-looking ex-KGB officer turned businessman, who became Perm’s governor. The experiment drew international attention and nationalist ire. Chirkunov resigned in 2012 and Guelman was removed in 2013.

“When you are the director of a museum, you are constantly collecting for the museum,” he said. “I put together a very good collection of Russian Povera. The Perm museum has the best works of many of our artists, Valery Koshlyakov, Sasha [Alexander] Brodsky as well as a very good collection of Anatoly Osmolovsky.”

Guelman is carefully calibrating his return to the Moscow scene. An archival exhibition about the political protest artists Pussy Riot, Pyotr Pavlensky and the Voina group ran from October through December 2019 at collector Igor Markin’s private Art4 museum.

“Over five years, while living in Europe, I suddenly realized that this is all great but it’s quite strange that I’m not doing anything in Russia,” he said. “Last February, when I came for a month to Moscow… various museums started making offers. I thought that I didn’t want to be banned again. I don’t need scandal. That’s why I decided that first I’ll do a pointed exhibition myself on Markin’s private territory, and if all goes well, I’ll go ahead.”

In February, his personal donation will be shown at the Tretyakov and an exhibition of Ukrainian art organized by him will be the non-commercial highlight of a new art fair in St. Petersburg.

“I want to keep on doing things that no one would do without me,” he said. In this case, his aim is to counter “anti-Ukrainian hysteria” in Russia.

“Even if art is not involved directly in politics, art has its own political interests. Art people want to live in a big world, not in a closed country, run by leaders who crave censorship and follow the Russian state’s tradition of persecuting artists and then appropriating their artistic glory.”

“Do we bear some of the blame?” Guelman asks, referring to those like him and other intellectuals who once collaborated with the regime. “Yes, we do. We understand this. That’s why I always say that I don’t judge anyone, because people make mistakes.”

Marat's Gift. Contemporary Art from the Guelman Collection

Moscow, Russia

15 February – 10 March 2020