James Butterwick, a passionate collector and dealer of Russian art

A crusader against fakes, who carefully avoids using that word, shows us around his new gallery in London's Mayfair and tells the story of his collection.

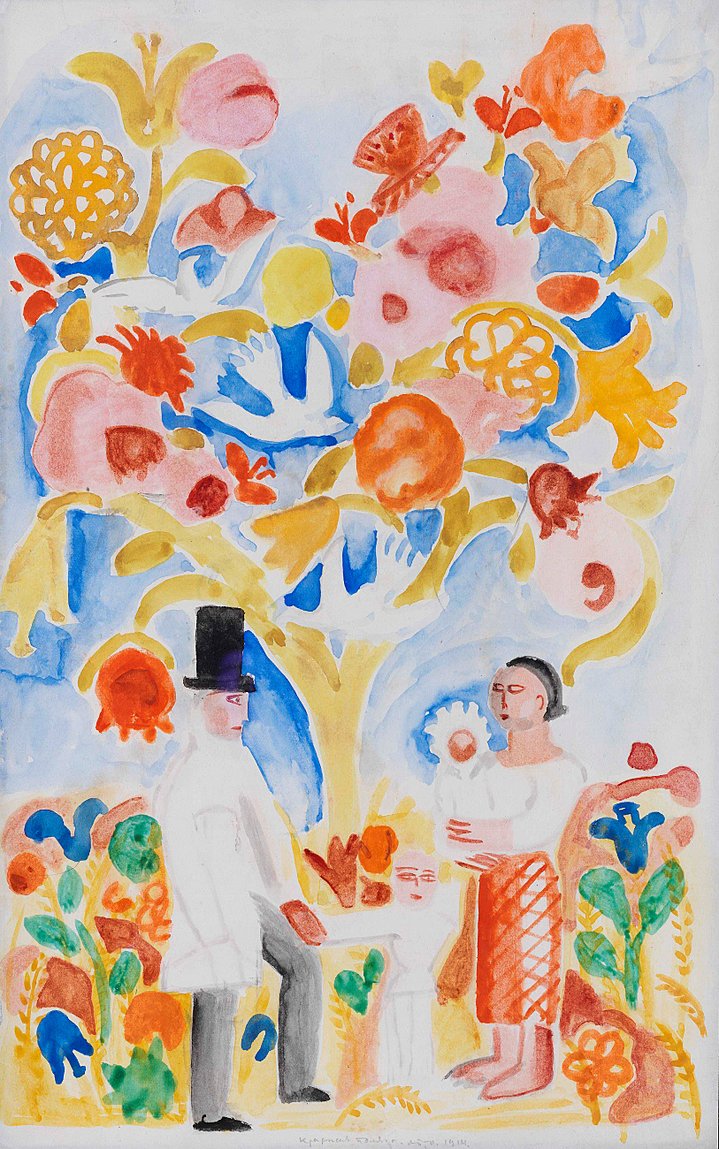

James Butterwick (b. 1962) is a flamboyant, adventurous character with strong principles, a great sense of humour and an extremely sharp eye. The secret of his success, both as a collector and a dealer, owes much to the trade’s principle: “Never buy a name. Always buy a picture.” The art market runs in his family’s veins and he spent seven years in London learning the ropes. In 1994, he moved to Moscow “where the action was” and started trading in his own name, having in the 1980s studied Russian in the UK and Soviet Union. He started his personal collection just three years after arriving in Russia. His first purchase was a ‘Group of Figures’ by Leon Bakst (1866–1924).

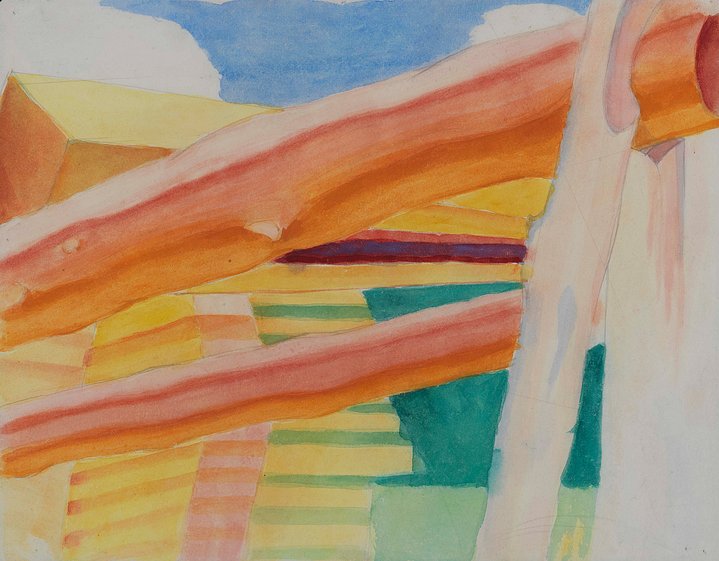

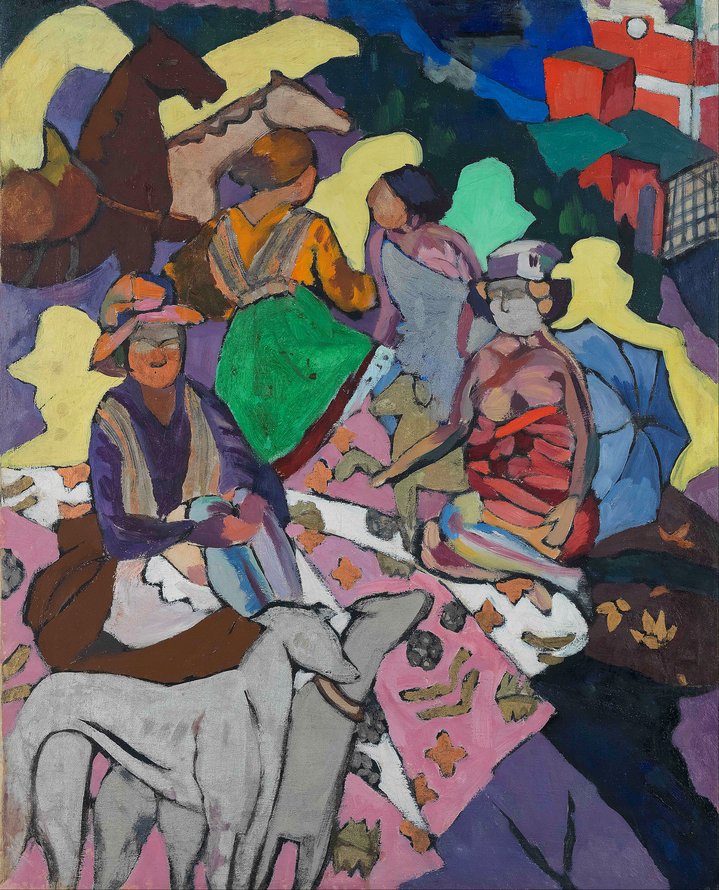

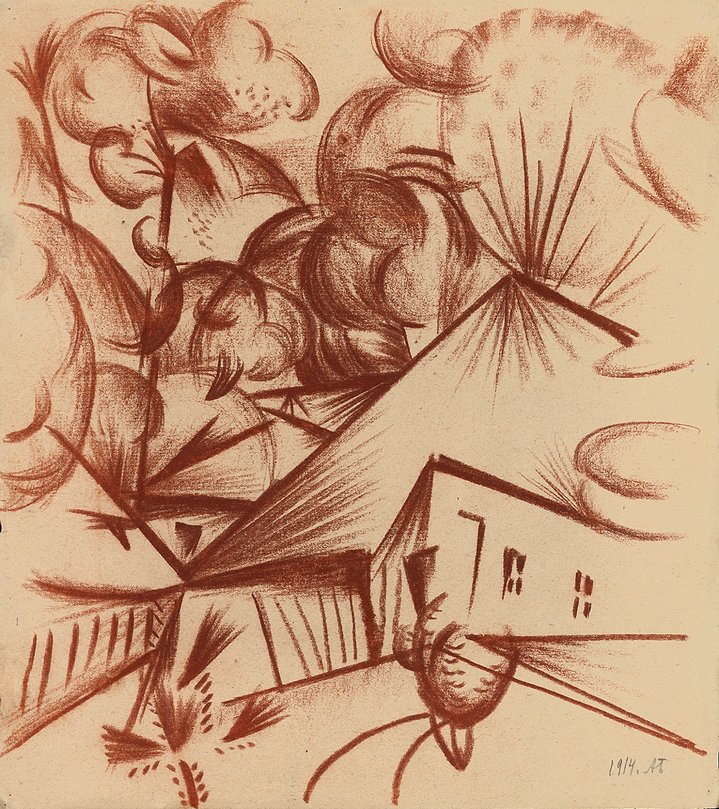

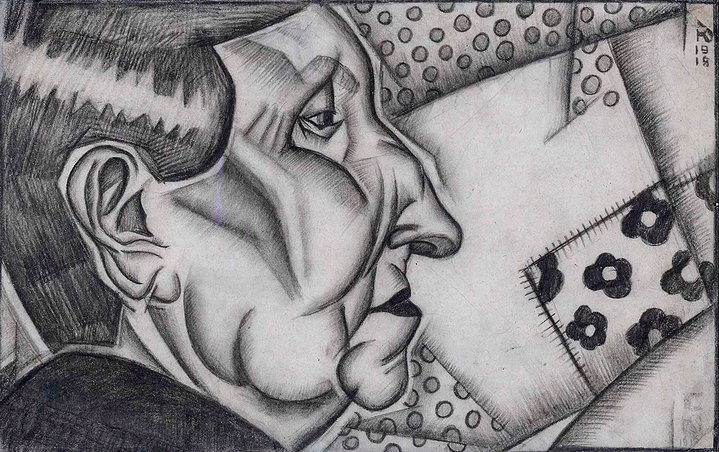

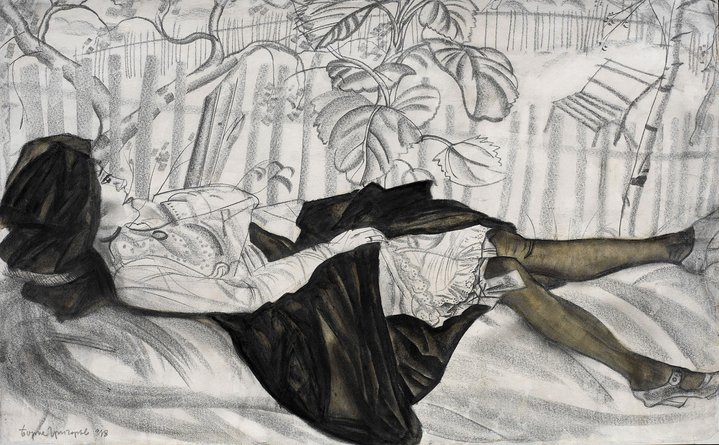

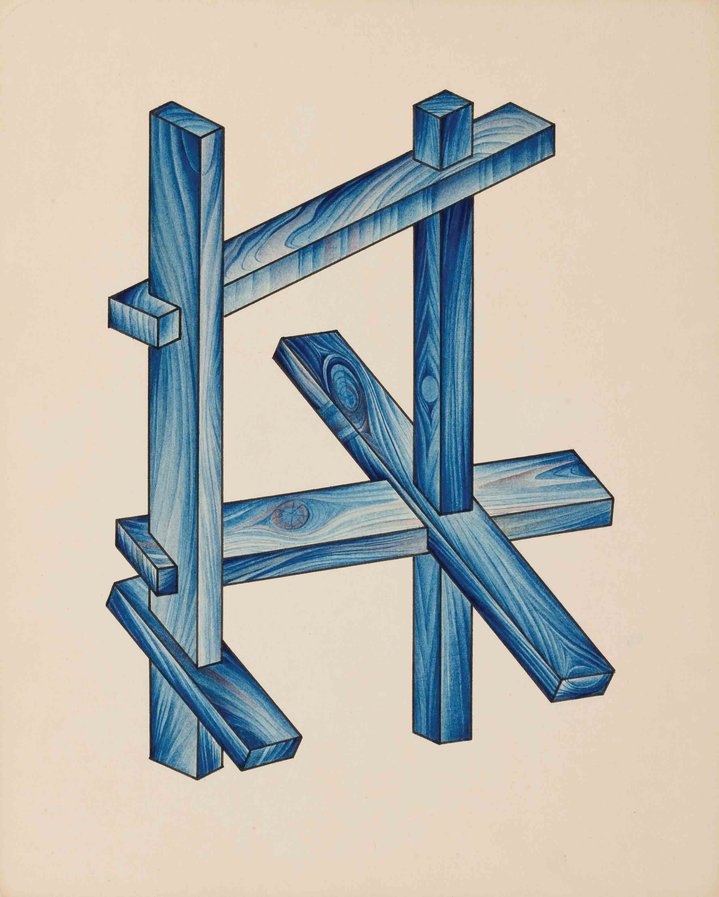

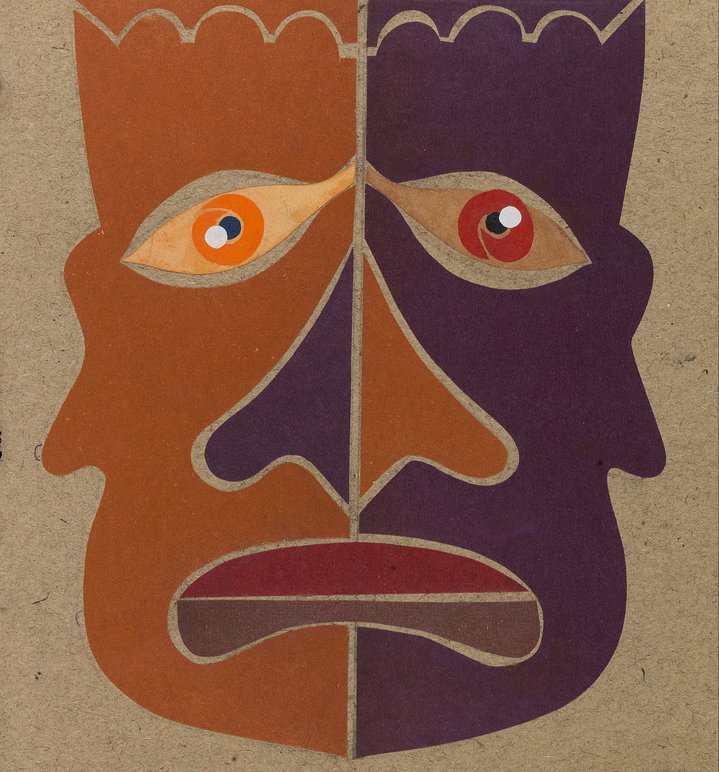

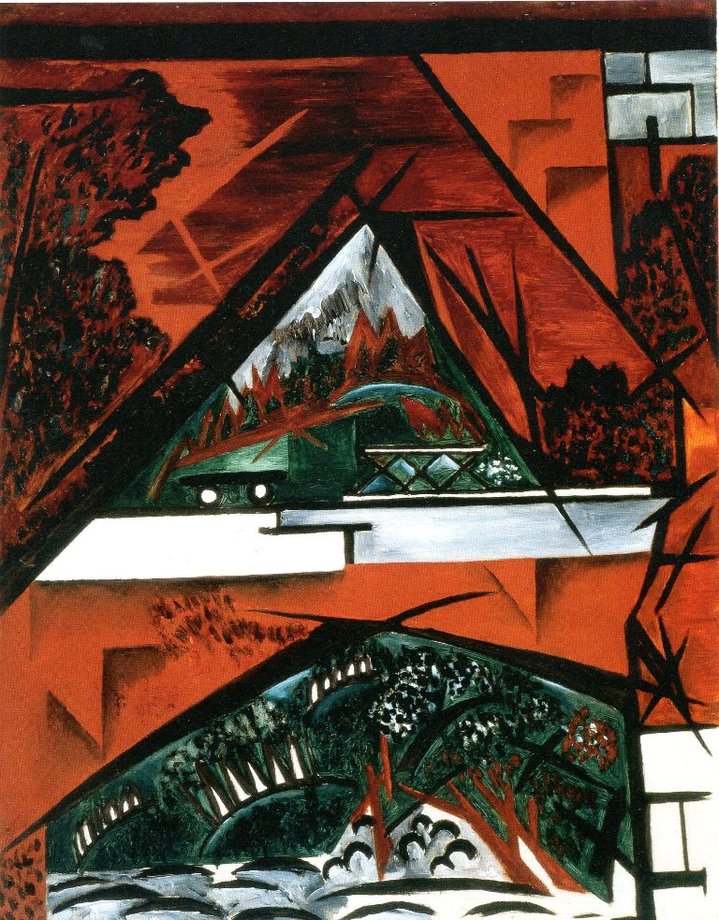

“There were then loads of sales and loads of collectors in Russia. They were interesting times,” Butterwick said during an interview at his new gallery in Mayfair. Initially, he focused on classics, such as Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910) and Valentin Serov (1865–1911), but also sought bolder and much more innovative artists, such as Boris Grigoriev (1886–1939) and Alexander Volkov (1886–1957). The Russian art of the 1920s and 1930s eventually became his magnet.

His approach to art collecting is intuitive. He acts on instinct and says that “when one is offered something, instinct should be the primary concern”. The history of his art collection is made of stories.

“I sold my collection in 1999, and then I bought it all back in 2008, paying six times more than the original price.

“And then I started to branch out a bit. I bought this Grigoriev for 3,000 GBP, cleaned it and asked a student to do some research. She discovered it had belonged to the great Russian singer Feodor Chaliapin (1873–1938)!

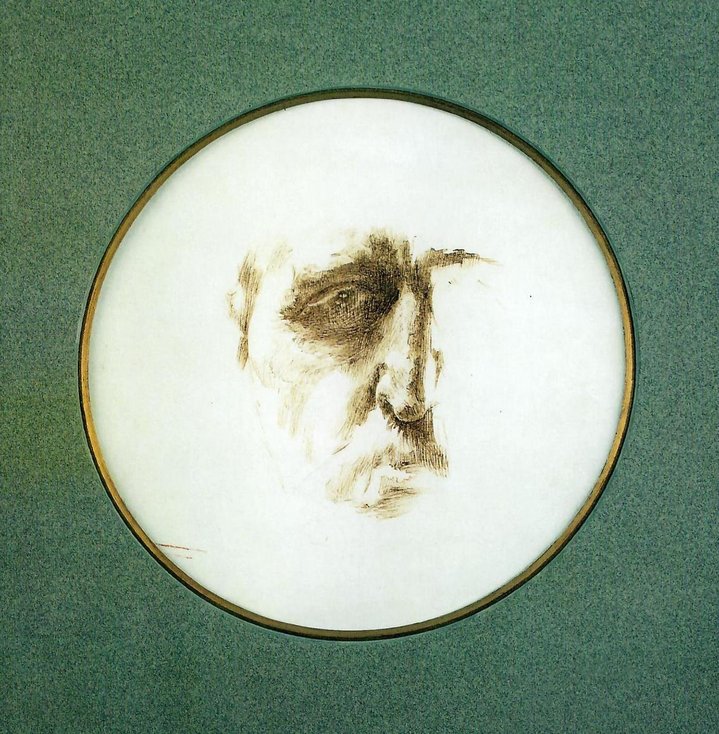

“I had a self-portrait of Vrubel painted in 1882-83. Moscow collector Valery Dudakov (b. 1945) bought it from his neighbour and then sold it to me. I showed it to the artist Valery Volkov (b. 1938) who dug through a pile of papers and found an old newspaper with that portrait on the cover, together with its whole provenance.

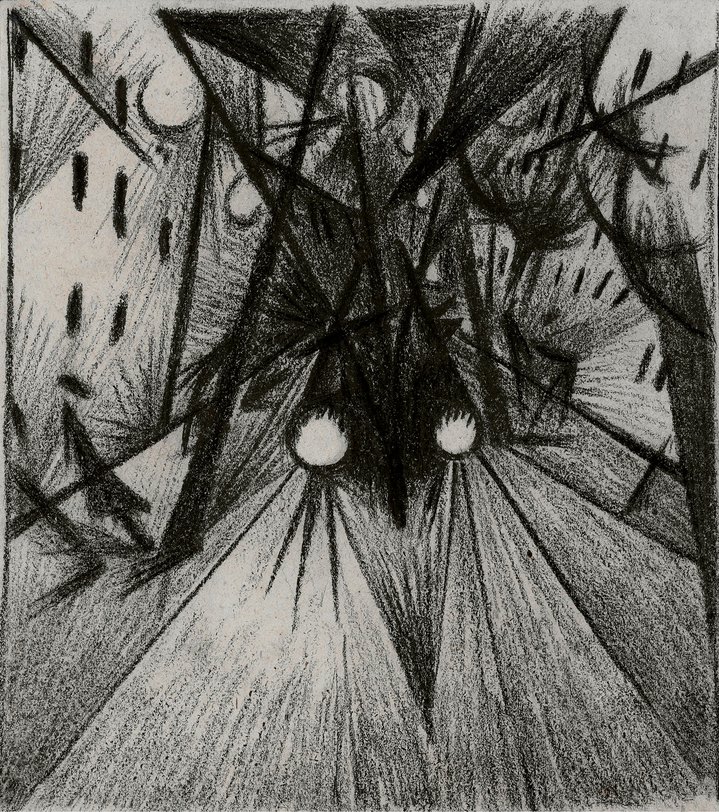

“There are times when you are offered so much money, that you have to agree to sell but nonetheless there are works that one is extremely loath to part with. One such work was a drawing by Alexander Bogomazov (1880-1930) called ‘The Locomotive’. It’s the most powerful work I have ever owned and my intention was to never sell it. Then a Museum came calling and when museums come, it’s very difficult to say ‘No’. It is one of the best futurist drawings - and now hangs in the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands.”

He is a late convert to Soviet Nonconformist Art, that he admires as much for moral reasons as for the talent of the artists who dared to challenge conformity. “The demand for Soviet Nonconformist Art is not too bad, but not as strong as it should be. There are some very important artists, some of whom died for their belief in freedom of expression. Many of the artists who defied the authorities to stage the 1974 ‘Bulldozer exhibition’ on the outskirts of Moscow are still alive, but they are not appreciated as they should be,” he argues.

Butterwick says his best year was 2014. It was then that he sold a portrait of Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), the artist who created the ‘Monument to the Third International’, by Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964). Butterwick found it in New York and says he sold it “to Russia”, without giving any details. He re-based his business from Moscow back to London in 2005, but trade with Russia has all but dried up. His explanation is that “in Britain, whether we like it or not, we have some respect for the law. In Russia, there is no such respect”. He continues to deal in Russian art, but the majority of his clients are now based in Europe.

Fakes have long been the plague of the Russian art market, particularly since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Butterwick says that up to 95 percent of the paintings he is offered are not the work of the artists named by the would-be sellers. Butterwick, an expert on Russian Avant-Garde, has for the last six years lectured on fakes. He argues that dealers are best at identifying whether a work is genuine or fake, simply because it is their own money which is at stake when they make a call. In his lectures, he names the scholars, art historians and galleries involved in the art market’s dark side, but he never uses the word “fake” or “forgery”, just in case there is a lawyer in the audience. Instead, among other warnings, he points out that should a work attributed to a well-known Russian artist, but lacking a detailed provenance or exhibition history, be offered at an astonishingly low price, any potential buyer should immediately head for the nearest exit.

In January 2018, Butterwick mobilised a group of dealers, art experts and scholars to get the Ghent Museum of Fine Art in Belgium to close down an exhibition, which claimed to show nearly 30 major works supposedly created by the leading artists of Russian Avant-Garde, but which had never been previously mentioned. The experts who signed an open letter denouncing the Ghent show included Kandinsky expert Vivian Barnett and Natalia Murray, co-curator of the ‘Revolution. Russian Art 1917–1932’ show at the Royal Academy in 2017 and curator of the ‘Jack of Diamonds’ exhibition at the Courtauld Institute in 2014. On December 16, 2019, the owners of the disputed Russian Avant-Garde paintings put on show a year earlier at the Ghent Museum of Fine Art, Igor and Olga Toporovsky, were arrested by the Belgian police on charges that included money laundering and dealing in stolen goods, according to the couple’s lawyer.