In from the cold

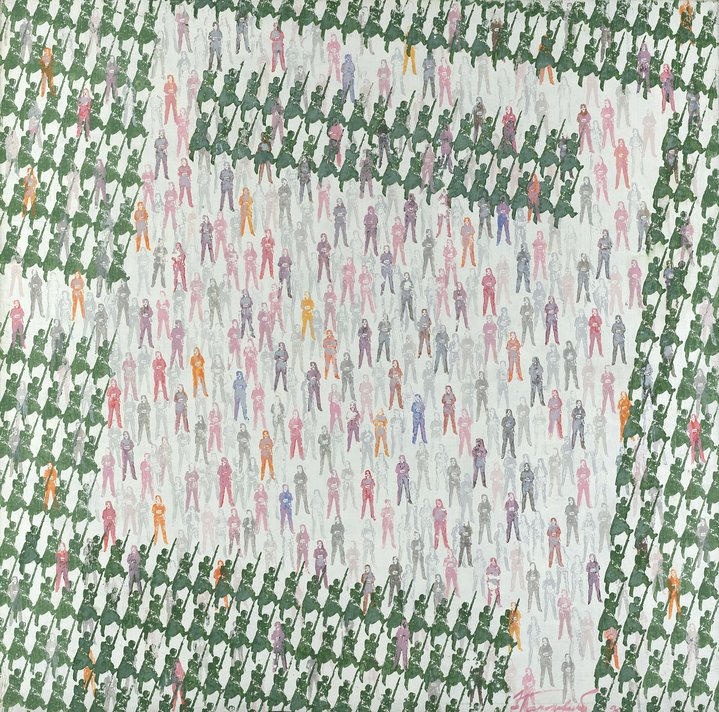

Vladimir Dubossarsky and Alexander Vinogradov. American Beauty, 2000. Oil on canvas, 145.5x145.5 cm. Courtesy MacDougall's

The post-pandemic Russian art market has a potential to bloom anew, according to Sotheby’s former long-time Russian art expert Jo Vickery, but is the resurgence of interest in Russian contemporary art sustainable this time?

A decade ago, the Russian contemporary art market was hit hard by the 2008 financial crisis. What followed was a long period of stagnation, leading many Western and Russian collectors to wrongly conclude that contemporary Russian art lacked talent and intrinsic value. This view became a self-fulfilling prophesy. However, the picture today is not so grim. Over the past few years, green shoots have been sprouting up, yielding better results in public sales. Today, during the pandemic, recent auctions in London and some new art initiatives in Moscow have shown an unprecedented level of buoyancy. But is this resurgence sustainable?

In the decade prior to 2008, all areas of the Russian art market grew at a fast pace in what became a bubble. There was the record-breaking John L. Stewart collection sale at Phillips de Pury in 2007, as well as several pioneering sales at Sotheby’s and MacDougall’s, which showed promising results. Despite this, it proved to be a story of “too little too late”. When the crisis dawned, there were not enough results to create a sustainable market. Most important of all, there were not enough collectors.

All this has been turning around in recent times, albeit gradually. These are early days and this resurgence has only lasted a few years, but the fact that the stagnation has been overcome is a huge feat heralding a kind of miraculous rebirth. It points towards a momentum built from the bottom up. This creates much needed confidence for collectors, both new and established ones, as well as strengthening the infrastructure which might prove to be more enduring this time.

If the market for Russian contemporary art grows slowly, that should be welcomed as a healthy sign. Fast-moving markets tend to be more volatile and speculative. The most recent Russian auctions in London in June bore all this out. They showed that even at a time of huge economic uncertainty with sales conducted online and limited chances even to view artworks before buying, the demand for Russian contemporary art was strong.

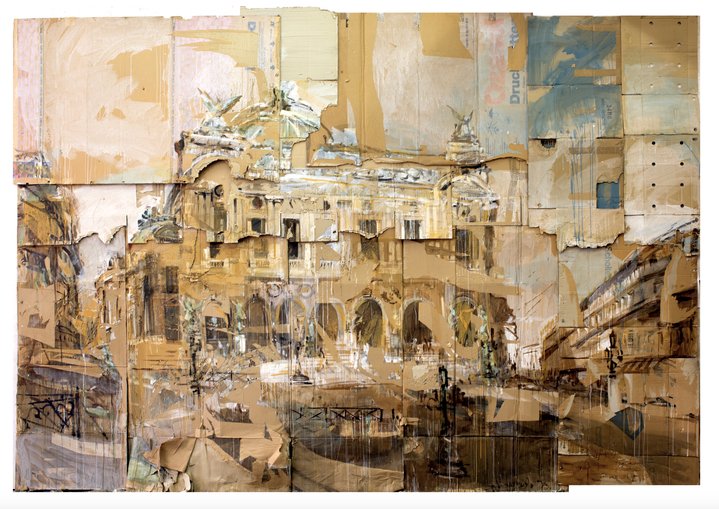

At MacDougall’s, three monumental works by Valery Koshlyakov (b.1962) all fetched stellar prices. The best of the trio, a view of the ‘Grand Opera de Paris’, which had been estimated pre-sale at £35-50,000, sailed well above, finally hammering down at £93,600. Significantly, this result outstripped the artist’s previous world auction record which was set at £72,500 at the market’s peak in 2008.

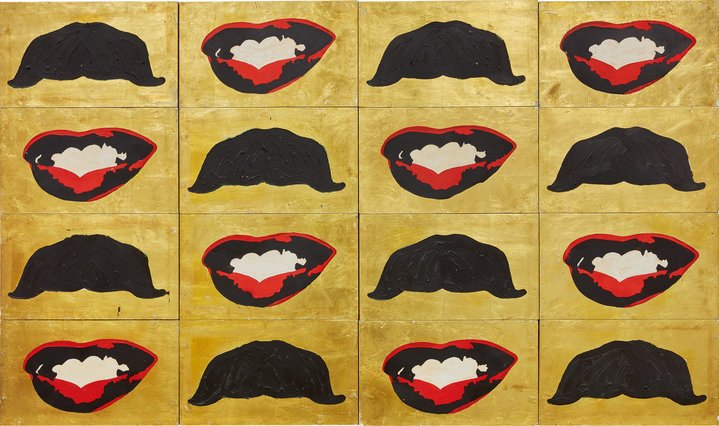

At Sotheby’s, Leonid Sokov’s (1941–2018) prices continued to perform well. One of my favourite lots in the sale was a large-scale 16-panel work, ‘Lips and Moustache’, which fetched £27,500, nearly double the high pre-sale estimate set by experts. Sokov’s previous world auction record was only recently beaten by a sculpture sold at Dorotheum in June 2019 for a six-figure sum. Despite a flood of paintings at both houses by second-tier artist Eduard Gorokhovsky (1929–2004), which might otherwise have gone unsold due to market saturation, only three works remained without buyers. Here, the top price was paid for ‘Group Portrait in an Interior’, painted in 1983, which sold for £50,000. At Christie’s Russian Sale which takes place online throughout July, one of the highlights is a panel relief by Dmitry Plavinsky (1937–2012), called ‘Lost Violin’, which was last sold in 2008 for £39,650. The new auction estimate for it is £30,000–50,000. This seems conservative, given its earlier sale was made over 10 years ago.

In Moscow, at Vladey’s June auction, there was a bold selection of Russian classic contemporary art, including Oleg Vassiliev’s ‘Space II’ abstract work, which was last sold at Sotheby’s New York during the boom in 2007. In that year, it was sold for $57,000. Thirteen years later at Vladey, it was sold for 140,000 EUR. The new price point may well prove to be justified. Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013) remains an artist whose works have a bright future ahead.

If these auctions focus mainly on more established artists, what about public sales for emerging ones? At Vladey there have been weekly online auctions during the covid lockdown focussing on the work of emerging artists which are proving to be an unprecedented success. In addition, the collector and gallerist Maxim Bokser’s new contemporary initiative on Facebook and Instagram, ‘The Ball and the Cross’, has proved to be an overnight sensation. Crucially, both these initiatives support emerging young artists during a difficult time. However, looking at the bigger picture, the longer-term value is in the creation of new collectors. This is key to unlocking the future growth of this market.

In order to reach its potential, the market for Russian Contemporary Art ultimately has to be sustainable both within Russia and on the international stage as an equal partner.

Russia’s contemporary artists need to be recognised, understood and visible all over the world. A selected few should be part of the global mainstream. Russia’s protectionist climate may dampen this burgeoning contemporary art market and that is a risk. For although Russia wants to project itself abroad as model of cultural excellence, it fails to seek and understand how strong and important values such as diversity and openness of expression have become popular ideals beyond its borders.

In spite of that, Russian contemporary artists have an unrivalled cultural heritage to bring to the table. The legacy of the Russian Avant-Garde in all its guises is often intrinsic to their work and this is a double-edged sword. The West fell in love with Russian Avant-Garde and is still in rapture. What the West needs now is to see past that historical movement and learn to appreciate the artists of today’s Russia, many of whom continue to preserve and explore the Avant-Garde in their art practices in a way that only those who inherited that movement can do.