Hoot, Hook and Pook and Pook: Sokov Sells Well

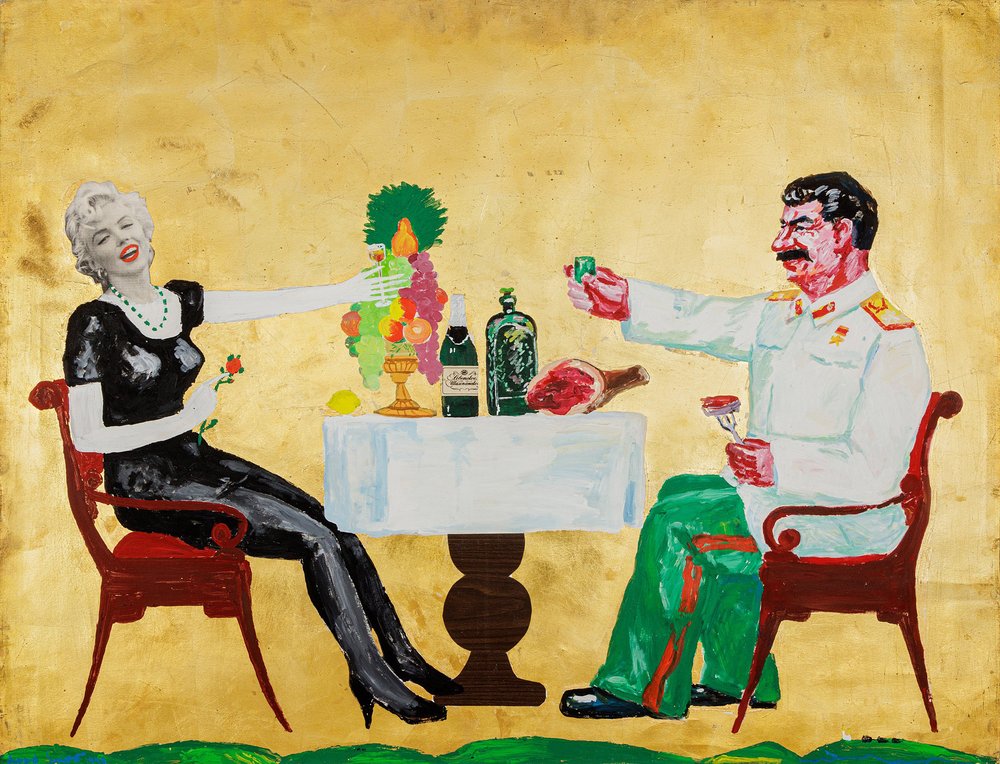

Leonid Sokov. Stalin And Marilyn At The Table, 1990. Image from the Pook&Pook Inc's website

An extensive cache of museum quality works by Leonid Sokov has been sold off in a small auction house in Pennsylvania, USA hammering home the notion that Fine Art can be found in the most unexpected of places outside the traditional mainstream centres of art.

On a crackly mobile phone line which sounded like the kind of bad transatlantic connection from a phone exchange in the late 1980s, I just catch Carole Rosenberg hooting ‘Yes that auction!’. Her incredulous tone came through the crackles, I waivered, should I ask her more or not? My better judgement guided us onto other ground, the Cuban artists she loves, a country to which she has dedicated decades of her life as president of the American Friends of the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba.

‘That auction’ was a fire sale of hundreds of works of art which had until now been the jewels of the Freedman Gallery at Albright College. Carole’s late husband Alex had been an art appraiser and art dealer and as an alumnus of Albright College (where he spent two years, and not his favourite according to Carole but still…) in the 1990s he bequeathed an impressive collection of art he had amassed, with big names, Salvador Dali, Helen Frankenthaler, and Leonid Sokov (1941–2018).

It is not hard to see why Sokov’s works appealed to this devoted democrat, who found art dealing complex, and disliked the trade in contemporary art in general. The fakeness, the games around investment in art as a financial asset, rather than true appreciation of artistic and cultural value. ‘I always knew I would end up in something as disreputable as the arts’ he joked with Anna Brady who interviewed him for the Art Newspaper in 2021. Alex Rosenberg’s collection of works by Sokov was part of a far larger trove of works from the 1980s and 1990s which had found their way by individual donations into the collection at Albright College. Except for the Zimmerli at Rutgers, it was undoubtedly the most significant institutional collection of the artist’s work. Many were donated by New York based art collector Roman Tabakman. That it was all now coming up for auction seemed unbelievable.

I have always had a soft spot for Leonid Sokov’s work, I think because I always saw within it, and still do, a natural child-like quality, a playfulness which makes anodyne the darkness in our world. Tragically, his father was killed at the front in 1941, the year in which Sokov was born, and as the story goes, he learnt how to make small wooden toys as a kid, and on one level I think he just carried on doing that. Moving to the USA from Soviet Russia in 1980, much of his work expresses the duality of belonging to two cultures, and with humour tinged with sadness, he plays with the contemporary myths that captivate or enslave us, whether Russian, Soviet or American. You can fit Sokov into various boxes, like Sotsart, a Soviet version of Pop Art, maybe even arte povera, but I think in the end he was just highly original, and simply a one-off.

The prices set by the local auctioneers Pook and Pook Inc., who advertised the sale as ‘Fine Art from an East Coast Educational Institution’, bore little resemblance to reality and there was very spirited bidding on each lot which meant that in the end everything sold. When I logged in at the allotted hour to watch and even try my luck at buying something, I discovered the whole auction was entirely online with no human voice, just two beeping sounds for ‘another bid’ or ‘fair warning’. I found myself watching different paddle numbers, some popping up repeatedly, and after a while I felt I even strangely knew 5060 or 5360 as they competitively bid up one another, but who were they really, I wondered.

For here, in the absence of anything other than a number there was no hook to hang one’s hat at the door to the arena and feel part of an event. There is something rather sad about the grand legacy of an artist, a benefactor, or an institutional collection on a college campus established once upon a time with lots of hope, the result of lives well lived and bungs of generosity, being sold off quietly online to anonymous people with no fanfare.

As it turned out, the works by Sokov collectively fetched just under $400,000 for Albright College to add to their needy coffers where in today’s world funding is under question at all levels. The issue with selling art, as every private collector knows, is once you have sold it, you cannot really get it back again. Many at Albright will miss this cultural heritage. It was a kind of reversal of fortunes - Leonid Sokov came to the USA to find economic and political freedom, and his adopted guardian angels in a rushed, hushed up blow sold off everything, and kept nothing.

Works with Marilyn Monroe and Josef Stalin, such odd bedfellows, proved popular in the auction. Their names may combine like poetry, but they were icons of two very different political systems and ways of life. In Sokov’s work you do not find a personification of Stalin the monster but more the myth and so it seems the humour is more palatable, you can laugh at the way Sokov juxtaposes Marilyn and Stalin, at a banquet table, toasting one another, or Marilyn’s trademark red lippy smile, placed alongside Stalin’s walrus moustache. How could anyone even dream up such an image? But fact is often stranger than art: Marilyn apparently layered five different shades of lipstick to make her lips appear plumper, and if you google ‘Stalin’s moustache’, you find a wealth of American journalists who have written screeds about the meaning behind it – Larry Getlin who writes for the New York Post once analysed the moustaches of dictators, and pointed out that Stalin’s moustache was ‘a reaction to the beards of leftist predecessors like Marx and Lenin’. Sokov is not the first artist to take an interest in appropriation and moustaches – a century ago Marcel Duchamp scribbled a moustache onto the Mona Lisa in his iconic L.H.O.O.Q.

For those interested in the mechanics of auction market psychology there was a textbook example of how ‘demand and supply’ works in the art world. The collection featured two of Leonid Sokov’s 1994 ‘Lenin and Calder’ sculptures. The better one happened to be the very first lot by Leonid Sokov to come up in the auction, a piece which had once been in the collection of the Rosenbergs. It sold for a respectable $11,250. Then, a few hours later towards the end of the auction the second one came up, this time made of metal not bronze, and with damage to the hand of the great Soviet leader.

However, by then there were far fewer lots left, and everything was selling well so bidders were under pressure, and eventually this poorer cousin of the first lot sold for a higher price! If I had been the buyer of the first lot, I would have switched off my computer screen with a smile at the end of the sale. As for my bidding luck, I managed to come away with Sokov’s ‘Around the Russian Idea’ a version of Malevich’s black square he painted in 1989 to which Leonid Sokov the interruptor applied a fragment from a postcard of a peasant ploughing fields.