Flash art

A film has been released about Russian artist and gallerist Alexander Petrelli who sells contemporary art from the lining of his coat. Is this for real?

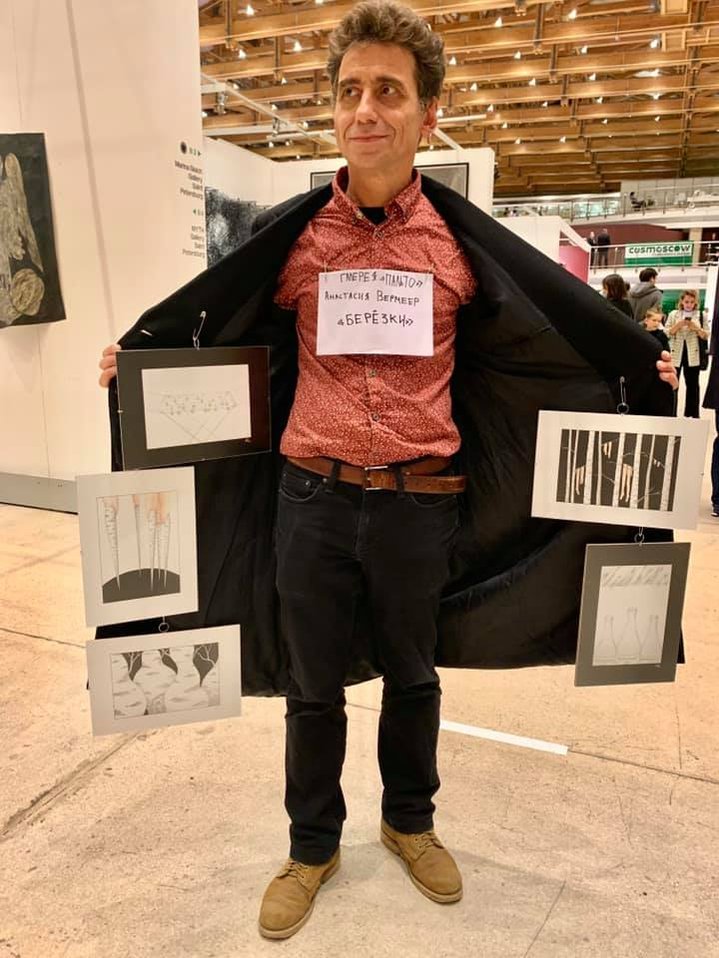

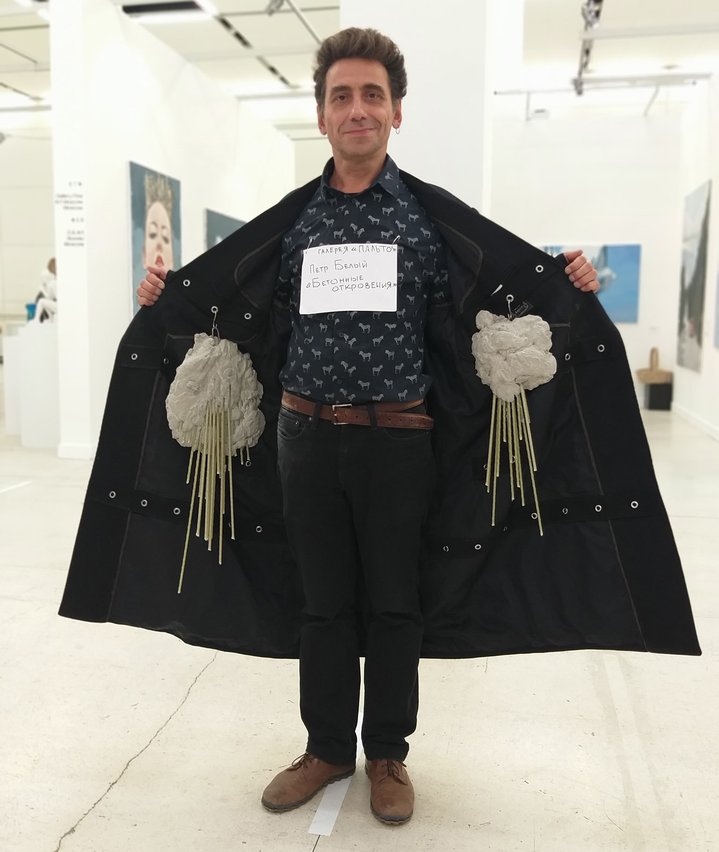

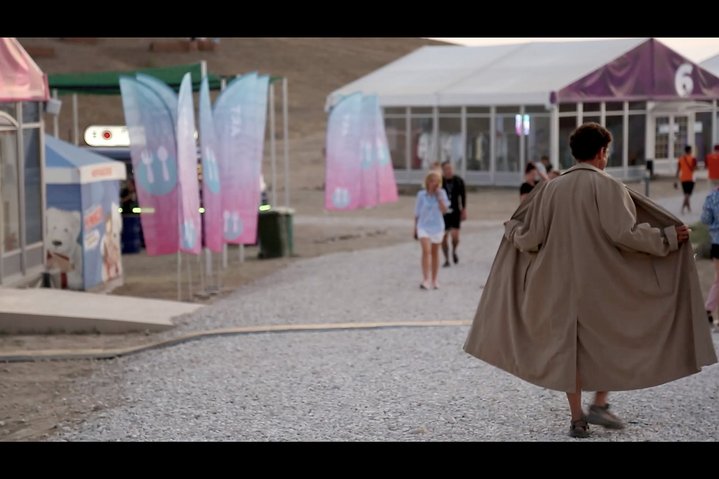

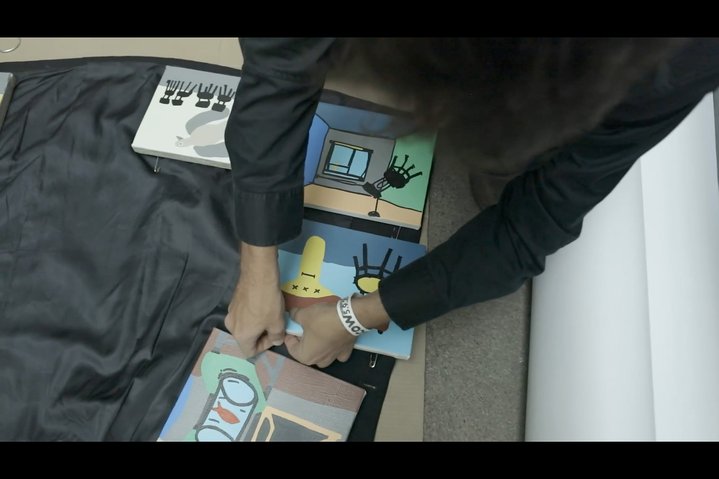

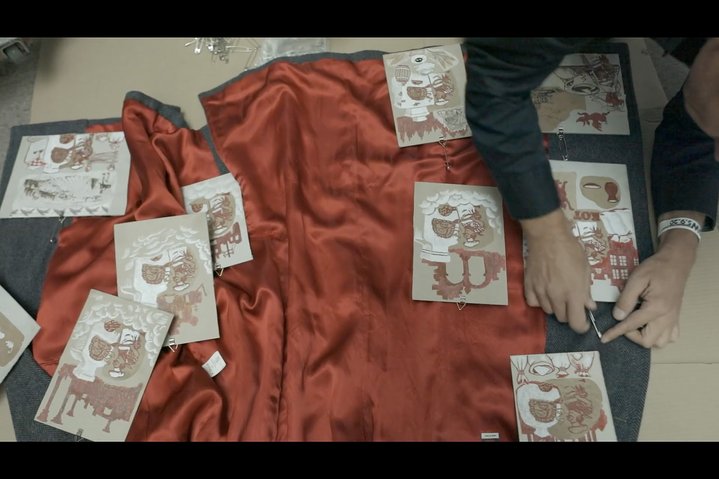

As the film (called ‘Overcoat’) opens, we see a man sorting through rails in a vintage clothes shop looking for an overcoat. He is Alexander Petrelli (b. 1968), an eccentric celebrity whose contemporary art gallery is no white cube. It is called the ‘Overcoat Gallery’ and that is exactly what it is, a gallery in an overcoat. Attached to the inner lining of whatever style of long coat he decides to wear at the art events he attends, are small works of art, revealed only when he opens his coat, much like a flasher. This is a short, funny and voyeuristic film (with English subtitles) by Irina Zvezdochetova about the intriguing phenomenon that is Alexander Petrelli.

Born and raised in Odessa on the Black Sea, he came to Moscow in 1991, the year everything changed. There was the putch signalling the Yeltsin decade and the origins of runaway capitalism, which had given birth to a handful of commercial galleries in Moscow: Aidan, Guelman, Regina and XL. Petrelli had arrived as an artist and it was initially a collaboration with the artist collective ‘The Peppers’ (Pertsy) which gave birth to the overcoat gallery in 1995. It was part prank, part performance at an exhibition of the pop-art duo Dubossarsky and Vinogradov.

At that time, art as a commodity had nuances of illicit goods, people believed art still belonged in museums and not in private collections and the character of the overcoat peddler was based on half-legal street traders in the Soviet times who hid their wares inside their coats. This wandering art salesman, however, has come a very long way since those early years. Eventually the Pertsy disbanded, yet Petrelli carried on and the gallery has been in existence now for nearly three decades. His coat materialises at various art events, fairs and exhibition openings, numbering over 500 appearances since he began, he is a kind of one-man pop-up gallery, long before pop-ups became fashionable in the mid 2010s. Except he is not really a pop-up gallery, he is the overcoat gallery, it is hard to define him/it. Then, as well as now, he has faced enormous challenges.

When they set out, Petrelli the artist and his contemporaries could not sell anything, their ephemeral art, embracing performance, conceptualism, installation, dada in spirit, was not commercial, the western diplomats and businesspeople who were living in Russia at the end of the Soviet Empire mostly bought works by non-conformist artists, such as Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016) and Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925–1995). This was the second Avant-garde like the second coming, popular and cheap – say, $500 for a masterpiece of the era which now might fetch $100,000 in a London auction.

We get to a shot of Petrelli sitting in the semi-dark at his computer editing a piece of his own video art which he admits, gesturing regret, nobody wants. He cannot sell it, but he has a deep need to create, he talks of spiritual hunger. What people want instead is the ‘Overcoat Man’, his alter ego, courted by a glamorous young crowd sipping champagne at gallery openings and some of Russia’s wealthiest art patrons, who are happy to be photographed beside him. It is a sad kind of fate: the film ends with a regular client of the gallery, who we see haggling over prices of works by Oleg Kulik, until the discussion takes a different turn: “Can I buy you?”

Performance art has an ephemeral character – it slips through one’s fingers like sand in an hourglass. People love it for that, but how do artists live off it? NFT art may offer new possibilities to trade in temporary events, like those bidding to own a famous sports game. Petrelli is rattled by the status quo of the art establishment. Over vodka with friends (drunk from a spoon) in the small, shared kitchen in a communal apartment, which was his home until he was forced to move out, he talks about the challenges of being different, his one metre square of ‘moving’ space is not always accommodated by art fairs organisers and the high costs of participation are mostly prohibitive.

I find myself wondering if this could this be the longest art performance ever. Petrelli’s first prank started in 1995, 26 years ago. The film director, Irina Zvezdochetova thinks “rather yes than no”. Conceptual art is often serial and spread over years, if not decades but what about art performances? There is something of the ritual in his activities. And is he an artist or gallerist? Difficult to say, a blend of both probably.

He prefers to see himself as an artist, because, he says, he has not been successful as a gallerist, he lives a frugal life far from the typical luxurious existence we normally associate with owners of commercial art galleries. These nuances of failure, both failing as an artist and as a gallerist, fit the kind of dada anti-establishment position of conceptual artists both during the late Soviet era and after (for example, this is a recurring obsession with Kabakov, who created an alter ego artist of poor talent). But there is no question, he functions as a gallery, collectors buy from him small works by great contemporary artists, many of them friends. There is not one definition of success. His is a fascinating, authentic existence, the film shows us the real challenges, but in the end this art flasher’s story is refreshing, edifying and should earn him some place in Russian art history.